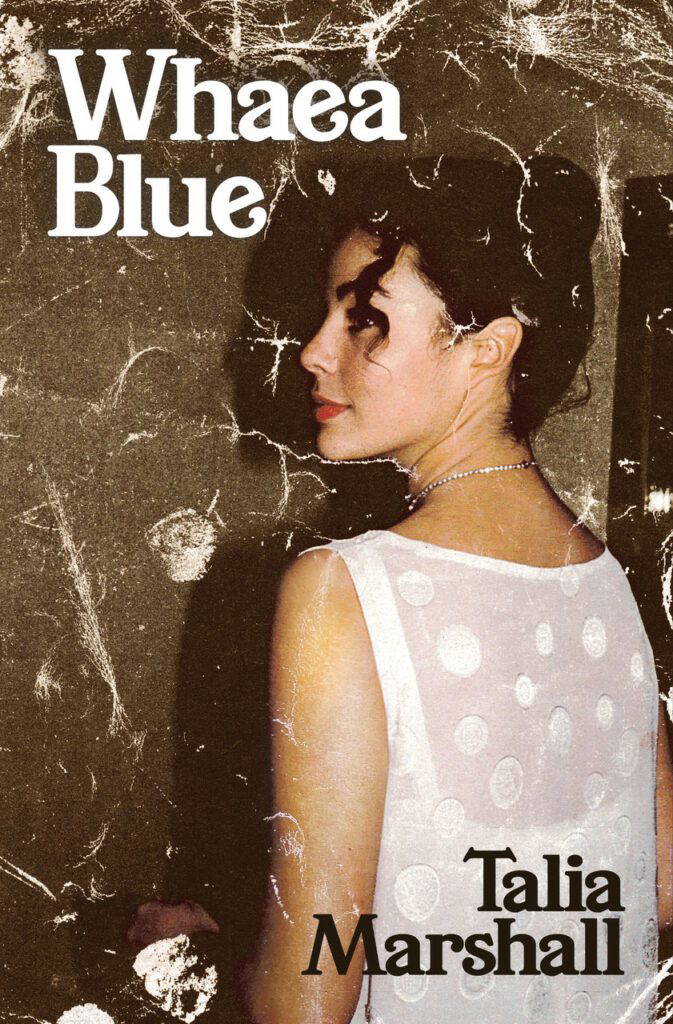

Whaea Blue

Whaea Blue by Talia Marshall. THWUP (2024). RRP: $40. PB, 352pp. ISBN 9781776920136. Reviewed by Ariana Tikao.

Whaea Blue is one of those friends who gets wasted and says the embarrassing things, the unfiltered. Talia Marshall’s writing is like the strong coffee my friend makes with the finest of grounds that permeate and sink to the bottom of the cup. It’s really good, but be ready for the hit. Marshall is a Dunedin-based writer of Ngāti Kuia, Rangitāne o Wairau, Ngāti Rārua, Ngāti Takihiku descent, and her set of interwoven essays is both personal and political, and show that these two things are in fact inseparable. Past and present co-exist. People, ideas, themes, and issues are interwoven throughout the text, which feels like a wonderfully Māori way of storytelling. Not linear or chronological, but more of a spiral.

The collection starts with “Echo Valley” where, as a toddler, Marshall was left behind at her Pākehā grandparents’ Mormon church by mistake. She gives a description of the curtains she may have wrapped herself in during her time of solitude there, and the baptismal bath she mistook for a spa pool later in childhood: ‘When I was eight I begged to be baptised so I could have a spa, but it didn’t happen.’ The next sentence is: ‘I was a fatherless child.’ This sentence comes utterly out of the blue—but I like how that element of surprise keeps you alert. Further in, Marshall builds on the relationship with her Māori father who she meets as a teen, and other relationships mentioned earlier in the book are slowly teased out. Each one is turned over and examined from different angles.

Whaea Blue is a ‘masterclass in honesty’ according to Becky Manawatu on the cover sleeve. The author often expresses doubts about whether she should write certain things, but seems compelled to do so, as she says ‘forbidden topics are like catnip to me.’ She writes candidly about her exes, including a chapter about her younger lover Isaac:

‘Isaac believed in auras, ghosts and his father’s steamed puddings. He could find pāua and drugs anywhere. The beautiful, natural way he let a bottle of beer dangle from his hand like he was holding the curve of a hip.’

Isaac is a charming meth addict who had been the victim of sexual abuse as a ward of the State. At first she sees him as an interesting subject, describing him as a ‘school project’ and admits he was also a distraction to help her forget the abusive relationship she’d just come out of. But after his sensitive claim to ACC for a lump sum payment is rejected, Isaac turns on her and the story becomes more like a horror movie, where the threat is around every bend, or standing outside of every window with a cricket bat. Although she is stalked and hunted down by Isaac, she still somehow has compassion for him, and expresses self-blame for creating the situation. I felt like saying ‘Don’t blame yourself, e hoa.’

Marshall writes first-hand accounts of psychosis, brought on by a bad trip after having too many magic mushrooms as a young person in Dunedin. Her writing gives important and rare insights into how debilitating it can be to live with the long-term effects of mental health problems:

‘… I miss myself at eighteen, so bolshy and certain in my own skin. I could have taken fewer mushrooms and not cracked my yolk… I spent part of my nineteenth birthday at A&E, waiting to see psych services, convinced I was evil.’

Māori and Pākehā relations loom large, and her essay about Dutch photographer Ans Westra interrogates ideas about story sovereignty, permissions and legacy and how these issues can be fraught with complexity. Marshall appears to have a love-hate relationship with Westra, but when she meets Westra as an elderly woman some of her criticisms fade. Marshall admits seeing something of herself in Westra: ‘Her pluckiness is admirable, I think; especially when she describes herself as a bit shy. I am shy too. And, like her, I am far more interested in what is happening in the neglected corners than on the main stage.’

Marshall shares her love of a small selection of images and ruminates about the people in them. One features a handsome young man in a white mesh singlet sitting on a couch, playing lovingly with his baby and toddler. This image resonates for Marshall because it reminds her of her ex, Roman, the father of her son, who acts as a kind of cultural conscience at times giving his ‘Nāti’ perspectives, warning her off certain subjects, and preventing her from accessing a Facebook page his aunties have created to identify people in Westra’s photographs.

The wonderful vignette “Postcard from Ans and the cocktail hour on the underworld” features Westra as a character in a magical realism style reminiscent of Twin Peaks. Westra, newly deceased, is disorientated at first, but meets Hone Tūwhare and they share kaimoana together on the waka wairua. Tūwhare gives Westra the best part of the kōura, as he sucks on mussels. This piece has a dreamy quality and reprises elements of other essays including the blue kēhua that haunted Marshall, who now rides an inflatable swan in the swimming pool. This section hints at Marshall’s abilities as a fiction writer—hopefully there is more to come.

“Pelorus Jim,” the essay about Marshall’s Pākehā grandfather, converges with the story of Pelorus Jack, the famous dolphin from Marlborough, and the Ngāti Kuia taniwha Kaikaiawaro. It is written in a stream-of-consciousness style, and draws on whakapapa, pūrākau as well as personal stories, memories and anecdotes. This is one of my favourite kinds of writing, reminding me of Nic Low’s Uprising (Text, 2021), where the writer interweaves their personal experiences, along with history, and ancestral kōrero, and guides the reader seamlessly between different times and stories.

While some of the chapters could have been made tighter by being trimmed down, overall Whaea Blue was a highly entertaining read with some laugh-out-loud moments, and some episodes where I felt like screaming aunty advice to her through the pages. Marshall often outs herself as an unreliable narrator and in the first essay says: ‘I suppose one of my many problems is that I think I can remember everything when really there are all these holes. And I fill them in with the silly putty of my imagination.’ I believe we all rely upon the recollections of others to inform us of what ‘may have’ happened in our childhood or even more recent memories. In Marshall’s case she has the self-awareness to recognise this human fallibility. In Whaea Blue she has combined excerpts of history, dreams, whakapapa, scholarship, observations, humorous episodes and hair-raising moments, and laid these fragments out like a multi-faceted memory mosaic, with her older self as the plaster that expertly holds the pieces together, to form this unique and colourful memoir.

Ariana Tikao is a Kāi Tahu artist of the sound and word variety based in Ōtautahi. She was an Ursula Bethell writer in residence at the University of Canterbury in 2023, and has co-written two books Mokorua and Te Rā: The Māori Sail.