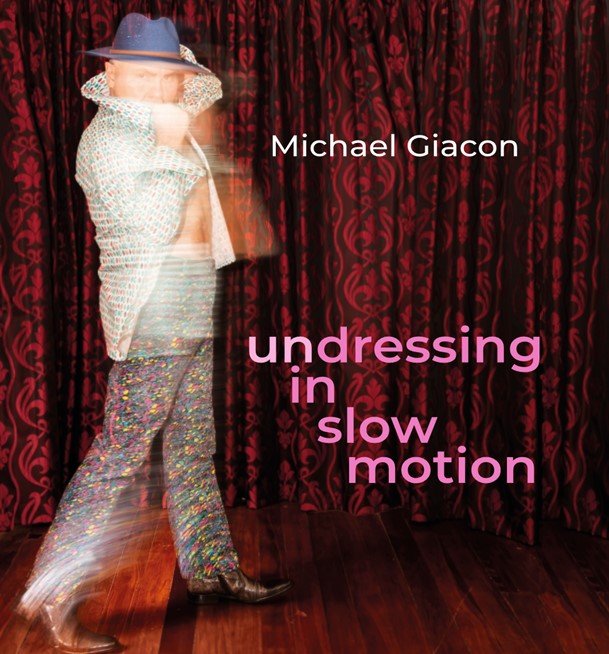

undressing in slow motion

undressing in slow motion by Michael Giacon. Michael Giacon (2024). RRP $30. PB, 99pp. ISBN: 9780473707743. Reviewed by Angus Smith.

As both a debut collection and one written by a queer septuagenarian, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Michael Giacon’s undressing in slow motion is preoccupied with the concept of time. From the opening dedication ‘in questo passato sempre presente’ (in this past always present) the style and subject of these poems cohere to create an effect akin to time travel. From a—not unhappy—Catholic childhood to an older age marked by both solitude and a deep communion with nature, the collection spans a personal history and emotional landscape, without a fixed beginning or end. Memories of stories told about his Italian family are inseparable from the speaker’s own life path. His world is one populated by physical reminders of the past, on a bus spying by chance a ‘secret public place’ demolished and left to ‘the tick-tock of meters,’ he remembers instead workshops full of ‘terrazzo, columns,’ seeing without seeing ‘a beautiful city.’ A callback to his forebears who laboured on urban projects now concealed beneath Auckland’s suburban conglomeration, reminding us that bolder visions of our present always existed and remain possible.

The author peppers greyscale text throughout, a unique technique to bring out the fallibility of memory:

‘1928 or ‘27 or ‘23 the S.S. Regina d’Italia leaves Genova

on her last voyage and sails into the Port of Auckland. Nino

is ‘four thirty’ years old according to his mother. He’s been given

cigarettes by their chaperone Luigi, 18 or 19, himself hooked

aged 7 to 10 by Scottish or English soldiers in exchange for eggs

from the family farm in Montebelluna during the Great War.’

Giacon combines multiple standard tenses to better portray a lived experience of time. A stanza break transports us from the death of one parent (‘on her phone she plays / played him singing / Torna a Surriento as only he can / could’) to the other (‘our mother loved trees’). Childhood ends (‘we scatter / ashes on forever’) just to be echoed in one’s seventies. Fears of abandonment in that early life (‘presents that hold / tight again, that still push away’) are amplified by the increasing signs of mortality at the other end, though paradoxically softened by the recognition of those family and friends who remain constant through life’s seasons (‘trailing in the wake […] I am with you; you are with me now’). Patterns of weather lend continuity and metaphorical ease throughout, as the narrator increasingly turns to the natural world for companionship (‘waves hold me sweet with another embrace’). But even that lodestone may topple through manmade climate change. Addressing such politics head-on is no easy feat in poetry, and unfortunately the results can be more cute than powerful, for instance a masculinity crisis personified as the sentient RaptaRex with ‘canines in the rear cabin, Fossil and Fuel.’

The book heats up with ‘Argento poolside / oh, my eyes / what they prise’ and ‘fabled gems on a chain / unmade great words jangled / for display huge in his bareness.’ It’s an interesting aesthetic decision how these gay love poems are boxed into their own section of the collection, with little overt queerness surfacing in the other three.

However, it’s refreshing that sexuality is not a source of dramatic family conflict and trauma in this book. Rather, it is granted a deserved spotlight on its own terms. Space is given to the weighty historical era of the Homosexual Law Reform Act, revealing how the gay community formed a genuine culture of its own through activism and mourning, as rich in reference and belonging as the Italian identity of the speaker’s own family. Compare the two great funeral poems of the book. One gathers a multicultural family in a country church near Katikati to farewell a relative ‘gone so soon,’ while the other sees a queer chosen family during the AIDS pandemic adorn their loved one’s coffin with ‘red stilettos ready for the yellow brick road’ and ‘a poem I wrote for you nine years ago.’ It’s immensely valuable to keep these personal recollections alive in the cultural memory, especially at this time of governmental failure to respond to an ongoing pandemic and moneyed propaganda against the humanity of transgender people.

Despite the poet’s attempt to draw a line from the eighties to the ‘samesame but different festival 2017,’ there’s no united gay/queer front like there once was in our increasingly digitised and atomised society. Not to say there wasn’t gay damage. Loss resounds through the speaker’s life, tolling with the refrain ‘all those boys always young.’ On a visit to his ancestral Belluno he observes ‘corners kissed warm / by daughters and sons hidden / yet holy, their romance no crime.’ Although the church remains a place of community and beauty even in the present (‘finding a faith / to fashion / from wrecked repressions […] healing our broken’), he remembers a past of ‘bashful boys thoughtful of fathers’ and can’t imagine a future of ‘happily ever after; that’s one fairy tale too once upon a time and far, far away for me.’ It’s a relief to encounter times in his life where he could finally revel in a gay identity. Classic signifiers abound such as West Hollywood, San Fran, Saint Sebastian and of course ‘Madonna and I are both from large Italian Catholic families.’

Is this all just a bit superficial? Then again, like in one poem where the speaker comes across a Jackie O look-alike against the not-quite-scenic backdrop of Coxs Bay, ‘any dazzle will do.’ Perhaps it is eloquent that his elder life is occupied instead by grounded urban rituals of self-care and solitary coastal immersions up north. The act of writing too is life-giving, the speaker rapturously composing poetry on seaside rocks in his ‘baptised notebook.’ Yet a chance acquaintance with a glider pilot reminds him that intimacy and love remains: ‘for one more wish if I lean right back / my guiding star an arm round my shoulders.’

Some may find the sprawling nature of the book challenging. Those early whakapapa poems concerning migrant Italian craftspeople in Aotearoa—not to mention a cross-cultural love story initiated by the Napier earthquake of 1931 (‘ending with beginning’)—could form a fascinating time capsule and collection of their own. However, in an environment where a tightly themed poetry collection makes for easy copy and funding applications, undressing in slow motion stands out as a work of genuine artistic ambition. The refusal to stay in one lane gives the book its character, and reveals Giacon finally as a true individual.

Angus Smith is an op shop professional and opportunistic writer from Auckland, with roots in Oxford and Aberdeen.