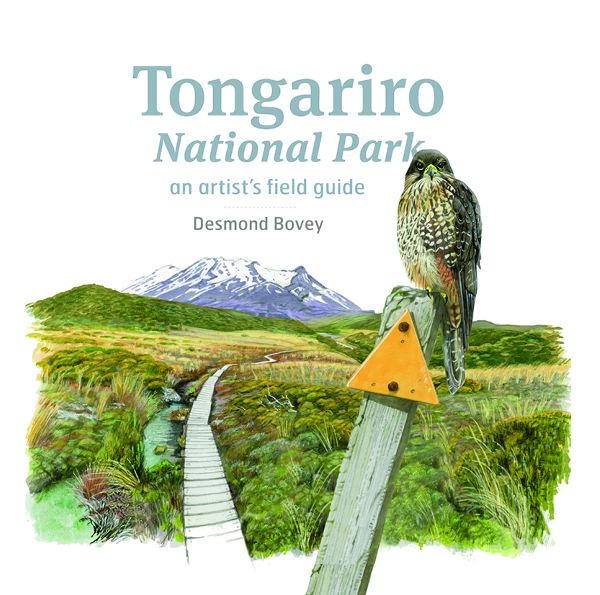

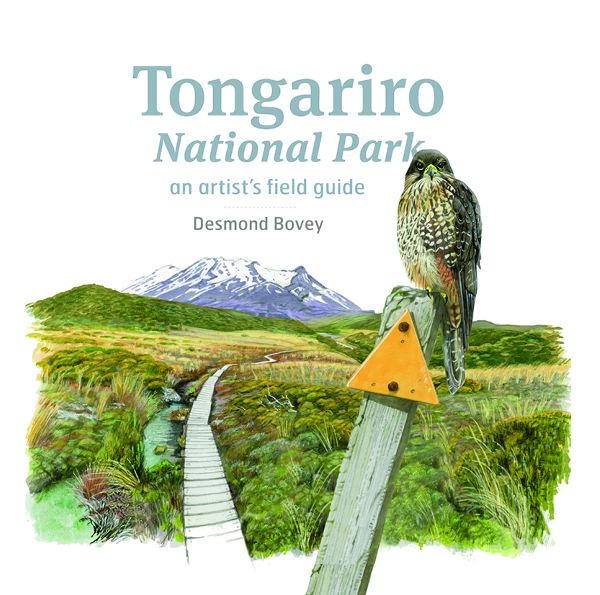

Tongariro National Park

Tongariro National Park: an artist’s field guide, by Desmond Bovey. Craig Potton (2023). RRP $39.99. PB, 200pp. ISBN 9781988550510. Reviewed by Andrew Paul Wood.

It might be argued that our national parks are already works of art in their own right. In that respect, Tongariro is one of the most beautiful. Artist Desmond Bovey’s beautiful illustrations in his new book Tongariro National Park: an artist’s field guide, only enhance this impression.

The Whanganui-born Bovey moved to France in 1982, where he would live for thirty years, acquiring nationalité, becoming a French citoyen in 1991. After studies at the Université de Franche-Comté in Besançon, Bovey took up the position of art director in a French communications agency. He came to specialise in the public interpretation of ecology and the environment, eventually becoming a freelance nature illustrator for various government and environmental organisations in France, Switzerland, Monaco, Germany and Réunion.

Since returning to Aotearoa and basing himself once more in Whanganui, Bovey has worked on projects for the Department of Conservation, Forest & Bird and various local councils. Artistic skill and a deep passion for nature are everywhere evident in this book. Every image is accompanied by lengthy explanatory captions. Not merely an exercise in nature art, Bovey also includes diagrams and landscape sketches to explain the ecological processes and geographical diversity of Tongariro.

This is Bovey reconnecting with the landscape and nature he fell in love with in his youth during a chance encounter with a kārearea, the New Zealand falcon.

It’s not just the art that forms the appeal of this jewel of a book. Bovey’s prose is every bit as exceptional and enchanting in the spirit of Henry David Thoreau. He is alert to the peculiarities and subtexts of language, as when he writes:

‘”The bush” is how New Zealanders usually refer to our splendid forests. It is a dismissive term, off-hand, faintly disparaging. The word is applied equally to a garden shrub as to a community of lordly podocarps. “Clearing bush” sounds like an action that might be morally justified; “felling a forest” does not.’ (p.21)

‘Which is not to say,’ he hastens to add, ‘that we do not love the bush. We do, greatly. Although we have to admit that, if the bush had a brain like ours, it would not love us back. In fact it probably sue us for maltreatment.’ (p.21)

This prose mastery is put to good use in mini-essays telling the story of everything from how at least three circus elephants died from eating mountain tutu (Coriaria plumosa), and the traditional ways Māori used the land, to the rather unpleasant-sounding John Cullen, former Police Commissioner, strike and union breaker, arrester of the prophet Rua Kenena, who ended up as honorary warden of Tongariro National Park and had the brainfart to introduce Scottish heather. Picturesque, yes, but also highly invasive.

Even the rocks get their time in the sun. ‘Tongariro National Park is one big pile of rocks,’ writes Bovey, ‘almost all regurgitated from deep within the earth. An exception is the vast amounts of pumice, hurled our way from Taupō.’ (p.188) He then goes on to explain the difference between Andesite, pumice, scoria, and other types of volcanic rock. In the previous section he dares to contemplate the return of the taiko (muttonbird) to the mainland.

Reading and ogling Tongariro National Park feels like a very spontaneous experience, as if we are following along at the artist’s elbow as he makes sketches and notes, but this is no misty-eyed romantic outing. This is as much an environmental polemic as an aesthetic feast for the eyes. Thus Bovey on the Tongariro power scheme:

‘Economic, scientific and cultural tensions were, and still are, inevitable. The authority of the time, the Ministry of Works, consulted only nominally with what today would be called stakeholders. They just drew up their plans and grabbed anything that looked clean and wet. To an engineer’s mind it all made perfect sense. At the time the significance of water to Māori, the moral and ecological consequences of such a massive grab, the rights and mana of land designated as “National Park”, and the health and mauri, or life force, of the Whanganui River (now granted the legal status of a person), were hardly considered.’ (p.100)

Bovey is consistently on point regarding human impropriety in the park’s ecology. He doesn’t mince his words and has no reluctance to dish out his frustration. Sometimes this repetitively negative tone can be wearying, no matter how justified.

Tongariro National Park: an artist’s field guide is a wonderful companion to one of our most lovely national parks, well worth perusing as homework before a visit, and small enough to conveniently tuck into a backpack.

Andrew Paul Wood is a South Island-based cultural historian and author, and the art and comics editor for takahē. His most recent book, Shadow Worlds: A History of the Occult and Esoteric in New Zealand (MUP) is out now.