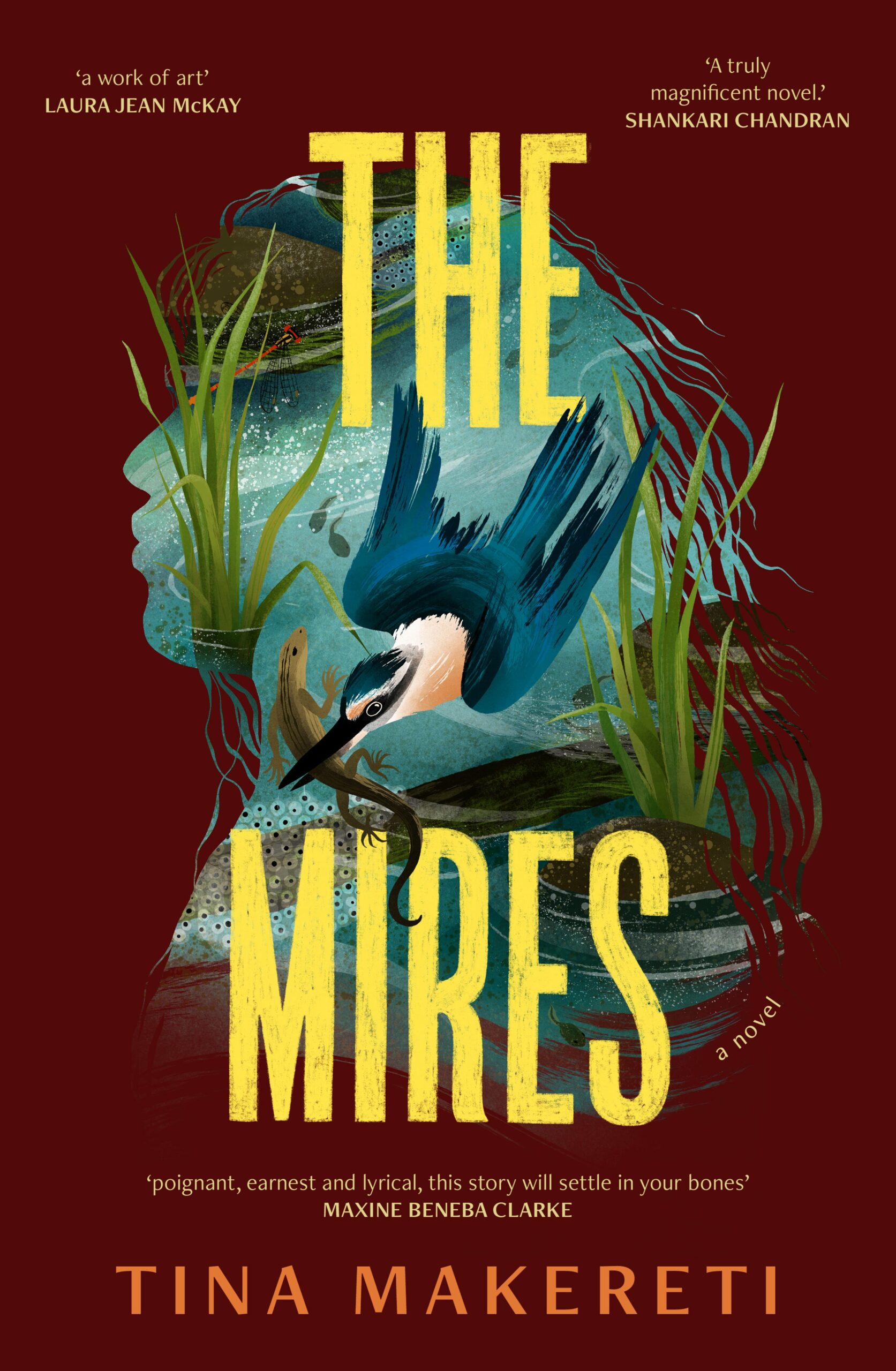

The Mires

The Mires by Tina Makereti. Ultimo Press (2024). RRP: $39.99. PB, 320pp. ISBN: 9781761153693. Reviewed by Tulia Thompson.

If the teenage character Wairere from Tina Makereti’s (Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Rangatahi-Matakore, Pākehā) The Mires were a colour, she would be bright seagreen, water-coloured and inky. She is an unusual teenager caught between worlds. A matakite.

The Mires is an ambitious novel that follows three women, Keri, Janet, and Sera, whose lives are interwoven via their shared block of flats. The book explores colonisation, right-wing extremism and climate change. It’s a story about place—Te Ātiawa whenua o Kāpiti—rich with the swamp that Keri’s daughter Wairere walks through. It’s also a story of displacement, through the pervasiveness of colonial harm. Sera’s family arrives after fleeing fires in Europe, while Janet’s son Conor’s extremism reflects the lack of a sense of belonging.

The story is at its most powerful when it’s hurtling towards an extremist event that we know to be inevitable, whilst Wairere senses the heavy load of Conor’s racism. When she encounters him for the first time at Janet’s house, she experiences ‘a sharp drop as if Wairere is in a car that has just gone over a hill and is hurtling downward, her stomach struggling to keep up with the rest of her.’

There’s a fluid, shifting quality to the way that we experience Wairere as possibly neurodiverse, intuitive and matakite simultaneously. Is she superpowered or is she hypersensitive and experiencing her senses strongly? At times I wanted more exploration of these aspects throughout the plot.

The depiction of Wairere as Keri’s ‘strange eldest child’ but also self-assured, and sharing a largely positive relationship with her mother, captures the zeitgeist of this generation of teenagers: ‘Wairere seems like an oasis of calm to her peers. Thus, at school she is accepted, if not popular, in all her strangeness.’

Wairere senses harm, can pick up on the feelings of others, and eventually is able to connect to the whenua through the swamp mother. It’s a course of action reminiscent of Kahu’s journey in Witi Ihimaera’s Whale Rider. It fits too that Wairere’s whānau are accepting of her gift. Her grandmother comforts her with, ‘Don’t sweat it too much though, bub. It is what it is. Lots of your tūpuna had it. Not me, or your mother, but in the whakapapa, it’s common as.’

Recently, Dale Husband did a lovely interview with Makereti in E-Tangata where she spoke about the pain of reconnecting with her whānau as an adult. ‘In a way, my story is the story of what colonisation does to us. You get your culture taken away, and then you get it back.’ Maybe Wairere represents what you get back, a new generation of young Māori women flourishing.

The Mires is arguably an example of ‘Indigenous Futurism,’ a term used by Anishinabe professor Dr. Grace Dillon to describe speculative works by Indigenous authors that explore futures where Indigenous characters exist and thrive. Imaginings that counter both colonial threats and existing colonial realities:

‘And as they travel, they lift time with them, so that the swamp becomes what it has always been, at every moment—primordial twitching ooze, prehistoric reptilian bird lands, ancient food storehouse—pātaka for the ancestors who rise out of the softening ground and join Wairere on her journey.’

One major course of action that culminates in a deus ex machina resolves the extremist plot a little too painlessly. In another plot thread, Makereti keeps the origins of the refugee family unknown, exploring the space that Othering opens up. Ultimately, this didn’t work for me as a reader (I longed to know the specificities) or as a plot device, because specific places and histories could have added more tension and more payoff. For example, when Sera soothes Wairere at the end, maybe she would be whispering a specific prayer.

Maybe Makereti’s decision to depict Sera and her family as refugees without a country of origin was about her discomfort with representing a culture outside of her own. There’s a broader question here about whether we should write characters whose stories are different from ours, especially if we inhabit more social privilege. We are as writers and readers necessarily confronting questions of authenticity, and who can speak for whom.

The depiction of Conor as a right-wing extremist is handled well. His version of Pākehā masculinity felt believable and familiar. Conor starts out as an online troll, but is lured by shadowy Johnny’s promise of heroism: ‘Do you know yourself to be a strong man? Could you shout it in the streets?’

There’s a challenging scene where Keri is momentarily drawn to Conor in the pub, when he blushes while talking to her. But after she rejects him, he shows sudden rage:

‘She watches the emotions cross his face like cloud over a landscape: embarrassment, disbelief, disappointment. Then his features settle into pure, cold fury.’

It reminded me of the proximity between misogyny and racism.

I would have liked the voice of the swamp to be more strange, poetic and limited than straight prose. Towards the end, when the swamp steps in as omniscient narrator, I was jarred by the sense that she wouldn’t be bothering to tell us this. But in Makereti’s hands, swamp mother cares for all the mothers, saying of the ‘I’m not racist’ Janet, ‘She is my daughter as much as anyone.’

The 2018 article “Indigenous science (fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral dystopias and fantasies of climate change crises” by Indigenous philosopher and climate/environmental justice scholar Kyle P. Whyte argues that for some Indigenous authors the dystopian future is already here, the ‘present time as already dystopian.’

I felt something of that weight reading The Mires, which sketches the crosscutting of colonisation and climate change. Sera and her family are fleeing fires when these events give way to flooding. Makereti points out in her author’s note that fires forcing evacuation are already happening:

‘They lived under blazing skies for weeks and, in the end, counted 6502 heat-related deaths in three months—the number seared in her memory because she had wondered how that could possibly be true. There was no memorial, no public outcry, no collective decision to change things.’

As writers and readers we are often confronted with questions of change. How much can characters change? It’s an uncomfortable metric based on our own sense of whether or not we believe people can change. Are we mired to our own racist histories, inheriting words that can only burn? How much change is possible?

In its closing pages, dislikeable yet stoic Janet quietly contemplates her own beliefs and impact on her extremist son. It’s about as hopeful as any one of us could be.

Tulia Thompson is of Fijian, Tongan and Pākehā descent. She has a PhD in Sociology and a Master of Creative Writing (Hons) from the University of Auckland. Her fiction and poetry is published in Niu Voices: Contemporary Pacific Fiction 1, Overland, Blackmail Press and JAAM. Josefa and the Vu, a fantasy adventure for 8-12 year olds, was published by Huia in 2007.