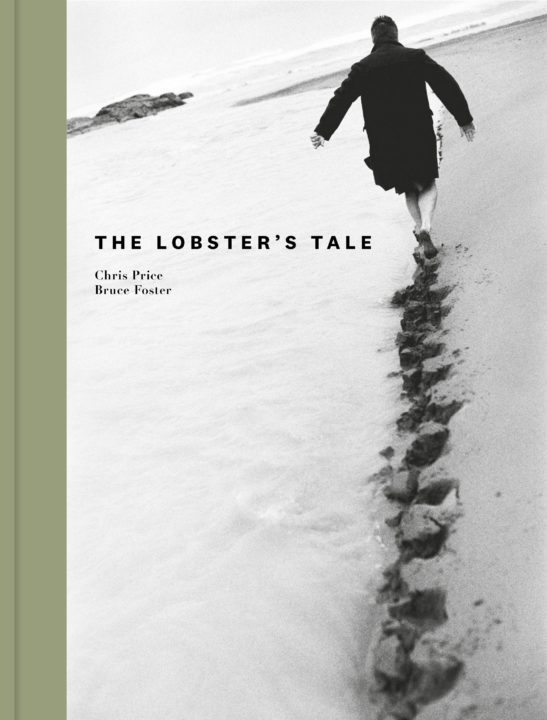

The Lobster’s Tale

The Lobster’s Tale by Chris Price and with photography by Bruce Foster.

Massey University Press (2021).

RRP: $45. Hb, 96 pp.

ISBN: 9780995137813.

Reviewed by: Jana A Thea

The Lobster’s Tale, written by Chris Price and with photography by Bruce Foster, is truly an interdisciplinary volume – not only between written and visual arts but also across non-fiction and poetry. The main text, while being beautiful, is at varying times informative, anecdotal, humourous, and thought provoking. The poem that runs along the bottom of every page (except full photo pages) is haunting and eerily enchanting. The photographs are noticeably selected and arranged to fit, and sometimes change, the mood of every page. The blank spaces in this book make it even more moving. The Lobster’s Tale is, a quite unexpected thing.

‘Lobsters are fearsome, handsome creatures, little living gods of our unconscious, totems of fury and unrepentant strangeness, half-fish, half-insect, living in the liminal space between ocean and pot, taking on their most vivid and attractive colour only in death, before which they are far better camouflaged.’ (p. 42)

While there are many lines in The Lobster’s Tale worth noting, the sentence above is a very fine indication of the quality and style of this book. With a light touch Price delves into our history, lore and spiritual journeys, across time and geographies, using the lobster to do so. This complex yet short book travels back to Cook’s voyage in 1769, to ancient Greece and Rome and then to 1944 and the release of The Unquiet Grave, a book published under the pseudonym Palinurus.

Price writes: ,…he [Palinurus] invokes his crustacean avatar as a friendly spirit guide on his dive into the underwater world of depression,’ (p. 36) further demonstrating the versatility of lobster and enticing the reader to think more about the spiritual implications of this crustacean.

However, this complexity of ideas combined with the fragmented style of The Lobster’s Tale does not easily lend this volume to accessibility. Because of the space in this book and how characters and stories are broken into sections, I needed to read it a number of times; once swiftly to get a vague idea of how all the puzzle pieces fit together and to know why, suddenly, on page 15 the tale of Sisyphus being banished to the lowest level of the underworld, Tartarus, was relevant to a book about a crustacean. Only after this was I able to go back and more fully devour each bite-sized section, while catching my breath in the spaces between. Still, not every section makes sense to me yet.

Then roughly half-way through (p. 41) you find a list of 48 different subspecies of lobster. There is no explanation, just like there is no title on any of the photographs. Though I find the not-knowing exciting, the puzzle-like nature of this book mightn’t appeal to the larger populace. It can be a little daunting and bewildering to understand just what is going on in The Lobster’s Tale but it does make it a most rewarding read, and being such an elegantly thin book, not too much of a task to reread it. Even several times.

Indeed, each time I read it I found something new. How the line of the poem on the bottom of the page interacts with photo and text, how this then creates a whole new three-dimensional mood, how I might have missed that had I only looked at one part of the page at a time, had I only looked once.

This is a book that invites scrutiny, and rewards close attention, and perhaps as increasingly rare a thing as the Homarus gammarus itself.