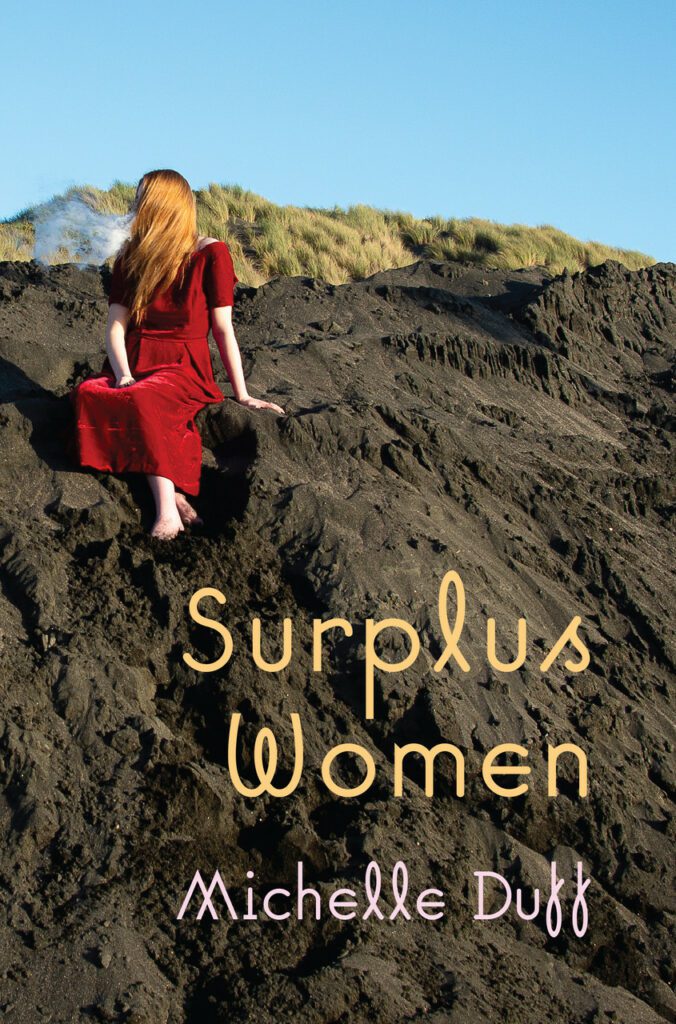

Surplus Women

Surplus Women by Michelle Duff. THWUP (2025). RRP: $35. PB, 240pp. ISBN: 9781776922284. Reviewed by Laura Borrowdale.

It’s hard to know what to make of the short story form, and I say this as a short story writer. It’s a spiky, awkward form that often seems to belong more on classroom desks than bedside tables. They have neither the lyrical brevity of a poem nor the narrative depth of a novel. They are seen as a stepping stone, a way to practice prose and hone craft on the way to a novel. And yet, if we can just take them on their own terms, there is something magical about them, something surprising, and something very, very satisfying.

Michelle Duff’s first collection of stories has this magic, along with a good dose of the surprising and satisfying. Duff won the 2023 IIML prize for fiction, but this collection isn’t the typically earnest and literary stuff you might imagine, but rather a chemistry lab of storytelling where a slightly mad chemist is seeing what happens if you add this to that. It’s a place to play and experiment with how to approach short form narrative, and this playfulness is evident in the stories. An investigative journalist by trade, Duff has described the lesson that she learnt in that role as one of detachment and distance: ‘It’s not your story. It’s not your pain. Your role is to observe, always; take notes, ask the questions. Listen. Convey’ (Duff, “My career was making me sad and anxious–then I learned to surf,” 2024).

Despite this sage advice from her journalism lecturers, it’s clear that they also taught her how to make a story belong to her, how to hook a reader and to carry them with you across the course of several thousand words. She knows how to observe, listen and convey. And these stories are anything but detached. The women in Surplus Women live riotous lives, do outrageous things, and, despite existing in some of the most ridiculous scenarios (elderly gymnastic rivals meeting as undercover spies?), manage to ring true.

It’s a clever choice of title, directing and redirecting us back to the position of women in each piece. It’s a reference to a part of our colonial history rarely told, that of the surplus women of Britain, the ‘husbandless, childless, unsatisfied’ who were shipped to the colonies as ‘a pair of hands, and as a womb’ (“Surplus Women”). The stories aren’t linked, but they revolve around the same central idea—the women who are forgotten, made small, patronised, and abused. The women who fight back, reclaim their power and make the best of their lives.

Duff starts with teenage girls, ‘four or five of them, a tight forward pack of fifth-form girls, bags slung off their shoulders, shirts untucked, hips and sneers and giggles.’ Her teens are tough, wrong footing the reader in their subversion of expectations. In the same way that Duff mixes rugby metaphors with giggles, here it’s the girls, rather than the boys, who brag about their sexual exploits, and who use their sexuality as a destructive force:

‘When the door clicked shut behind her, she had a new swing in her hips, and she let her mouth hang open just a little wider, wider, until her tongue was visible hot and pink between her teeth.

If slut was what they wanted, then Jess would give them slut.’ (“Easy”)

These teen girls, or others much like them, reoccur in the collection, as do mothers and their gaslighting partners, the kind of men who tell themselves they’re allies but passively aggressively tell their stay-at-home wives that they don’t really work. Duff also targets the inequality of parenting young children, of the woman’s load even in relationships that offer a semblance of equality and allyship. If this feels like well trodden ground, well it is, but there’s still something chilling about passive aggressive husbands. Sash, a detective in “Torn,” can recognise that, ‘Feminism has a lot to answer for. Re-packaging exploitation to make it seem like agency,’ as she interviews teenage prostitutes, but is unable to see the same in her own situation. Her husband guilt trips her, critiquing her ability to parent as well as work, by shouldering the burden of his own children, saying, ‘I’ve got this big meeting today, but I’ll try to get away so at least one of her parents is there for her, okay?’

The politics of the collection aren’t subtle but the directness with which Duff brings them to bear on the stories is refreshing. The collection wears its feminism on its sleeve, the critiques of patriarchal systems delivered by women sick to the back teeth of being told they need to be quiet and submissive. They aren’t here to take prisoners, and Duff endows them with an overt unapologeticness, like Genevieve from “Spook,” an elderly spy keeping watch on the protest movements surrounding parliament, who trades zingers with her male minder:

‘Plus, Kim Basinger, the whole femme fatale thing… don’t you find that a bit of a cliché? It was already so dated, even in the 1990s. Women are more than just ciphers for men to project their sexual fantasies on to, you know.’

In the final story, “Toxic,” the main character Ros thinks:

‘[A]bout a story she’d covered around here many years ago, when she was a junior reporter, about a local women’s weaving group. I wish I could do that, she’d said, admiring their work. But you do weave, one of the kuia had said. You do it with your words.’

It’s a fitting end to a book that proves the value of the short story form, as a place to play, to experiment and to weave together the threads of disparate lives into one satisfying, surprising collection.

Laura Borrowdale is a writer and educator from Ōtautahi Christchurch. She regularly reviews for the Otago Daily Times, and her short fiction is widely published. Her first collection of short stories, Sex, with Animals came out with Dead Bird Books in 2020.