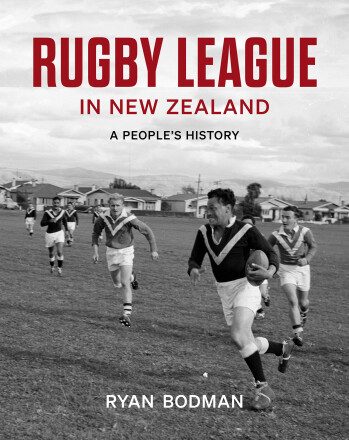

Rugby League in New Zealand: A People’s History

Rugby League in New Zealand: A People’s History by Ryan Bodman. Bridget Williams Books (2023). RRP: $59.99. PB, 364pp. ISBN: 9781991033444. Reviewed by Robert McLean.

I remain more convinced than not that an interesting book can be written about almost anything at all; which is to say, such books may throw an unexpected light on the world’s nooks and crannies, on the mundane, or overlooked, and by so doing broaden and deepen our senses of communality and connection. I can imagine fascinating histories of, for example, double-entry accounting, sewing machine repair, or wallpaper. Not that it would be easy to write such books—just not impossible. And given how hard it apparently is to do—given their scarcity—it is a particular pleasure when one does come across such a book. Ryan Bodman’s Rugby League in New Zealand, if not quite fascinating, is undoubtedly interesting and surprising. It casts its net widely while enthusiastically and thoughtfully pursuing its unapologetically sporting theme, including by drawing on first-hand interviews and thorough archival research. And yet it is a book that those without an interest in the game might enjoy more than those who do.

Bodman ‘explores the relationships that developed between rugby league and a number of diverse communities across New Zealand during the twentieth century,’ which is contextualised by ‘economic, social, and political changes that have shaped modern-day New Zealand.’ Pars pro toto, many of these relationships constellate in the Waikato where rugby league took especially deep root. In one of his many engaging byways, Bodman teases out the intimate webs of connection amongst the Kiingitanga, which did much to back the game, and Waikato Māori and working-class Pākehā, particularly the coalminers who had a strong sense of solidarity with economically marginalised groups, including local Māori. Bodman emphasises the game’s self-perception as a broad church, not least of all in its conscious eschewal of racial barriers that barred entry to other sports, which instilled a strong sense of pride in its aberrant positioning against ‘middle-class sporting norms.’ He notes, too, that Waikato Māori were ‘not encouraged’ to play rugby union and that it only gained popularity in such areas where Māori enjoyed relative affluence or wider social privilege, which frequently corresponded to ‘more harmonious relations with European society,’ an illusion from which Waikato Māori were altogether bloodily disabused by the settler state.

Rugby league for Bodman is the code of the freezing works, Huntley, the working class; rugby union is that of exclusive boys’ schools, sheep stations, watercooler expertise. These anecdotal characteristics shifted over the century Bodman examines but they have in his view cast the codes’ respective die. Whatever their relative popularity or reputation, both games are global minnows relative to the juggernaut simplicity and richer-than-Croesus oligarchical wealth of football/soccer. Part of Bodman’s story is that the rugbies are colonial legacies. Whereas football can be easily played on a dusty village backstreet, rugbies require the trappings of established settlement and privilege. They are also complex games with often indecipherable rules, union most of all, which is esoterically recondite to the point of incomprehensibility. League is often maligned for its supposed dumbness; union is for the rural sophisticates beguiled by its combination of thuggishness and subtlety. In the United Kingdom, it is a game for public school hearties and here it has not entirely cast off its Brahmin origins. Bodman incisively essays why the respective rugbies took root here and ways in which the codes have differed both on and off the field, much of which he seems to attribute to league’s combination of minority populism, payment for play, and social progressivism.

Not that everything was wine and roses, of course, but it beggars belief to imagine rugby league committing such triumphs of hubris as the New Zealand Rugby Union (NZRU) did when it omitted Māori players from tours to South Africa and allowed the 1981 Springbok tour to go ahead. One hundred and fifty thousand New Zealanders—or 6.25% of the population at that time—signed a petition supporting a policy of ‘No Māori’s, No Tour’ before the All Blacks’ tour of South Africa in 1960. Naturally, this was ignored by the NZRU, a turning of the supposedly colourblind eye that is at best a national embarrassment to this day. Rugby league, despite its early professionalism and the economic prerogatives that came with it, certainly has a creditable record by comparison, and Bodman presents it in sympathetic detail, the occasional wart along the way notwithstanding.

The socioeconomic and ethnic aspects of Bodman’s contextualisation of the game are handled with delicacy and insightfulness. He notes that Māori and Pacific people are the New Zealanders most likely to experience relative material deprivation; they are also significantly overrepresented in the professional and representative ranks of both rugby codes and the proportion is continuing to rise. Bodman, to his credit, is prepared to ask why and to offer some answers. Noting that ‘the structural forces that operate to elevate particular outcomes over others’ have been at best scantly examined, he suggests a ‘hoop dream’ motivation is at least partly at play, whereby professional sport is a potentially rapid and generational opportunity to leave behind poverty and ‘provide, survive, and thrive’. Furthermore, whereas conscious and unconscious bias and prejudice might dissuade such young men from pursuing a career in for example medicine or law, they are literally hot property in the sports entertainment industry—there they are wanted. Bodman links this pseudo-positive discrimination to a sporting version of the martial myth: over-representation on the fields is a physical inevitability. This is most discomfortingly hymned in the hoary adage loved by Kiwi commentators that so-and-so is a ‘natural athlete’, which shades into the same logic of the soldiers of the Māori Battalion being natural born ‘warriors’, rather each group’s success being attributed to training, dedication, ambition, and suchlike. Besides, Bodman suggests it is not a given that young Māori and Pacific men ought to prize ‘acumen in collision sports . . . above other cultural alternatives.’ Nevertheless, many seem to do so and most of them never even get close to earning a living from the game, the rewards of which are often either six or seven figure contracts or nothing at all. And the years spent devoted to pursuing athletic rather than academic excellence cannot be reclaimed as a business expense.

Bodman’s book declares itself ‘a people’s history’ and te tangata is held firmly and lovingly at its heart. Despite the concussive, bruising game with which it grapples, it is tender and often humorous as well as thorough and even-handed to boot. There are many unexpected detours along the way. The effect of the 1980s and 1990s neoliberal ‘reforms’ is discussed in surprising detail and from a novel point-of-view. Another brief but interesting diversion discusses gangs’ involvement with the game. If you’ve ever wondered what gets those Quixotic Wahs fans aquiver, this book is a good place to start along the way to understanding. Even if that isn’t you, if you would like to revisit familiar waystations of New Zealand history but see them from an unexpected angle, you might suitably surprise yourself by opening Bodman’s book, which once again BWB have produced to an admirably high standard. It is a fine addition to the growing contingent of New Zealand social histories.

Robert McLean is a poet, critic, reviewer and PhD candidate at Massey University studying representations of state-sanctioned violence in New Zealand poetry. His collected poems were published in 2020 by Cold Hub Press. His new album is coming out with Failsafe Records later this year. He lives in Lyttelton and works in Wellington for the New Zealand government.