Poorhara

Poorhara by Michelle Rahurahu. THWUP (2024). RRP $38. PB, 344pp. ISBN 9781776921287. Reviewed by Emma Hislop.

Tragedy and comedy are perfectly paired in Poorhara, the debut novel by Michelle Rahurahu (Ngāti Rahurahu, Ngāti Tahu–Ngāti Whaoa), a road trip story that swings between the hilarious and the heartbreaking in magnificent fashion.

‘If the ceiling burst, the landlord might think of selling the land under them.’ This first line encapsulated for me the predominant feeling in the novel, one of precariousness. Everyone in this novel knows exactly what they don’t have—this is a book about a lack of security and too much pressure and holding on and longing.

First we meet Erin, who is helping her Aunty Ann clean houses:

‘She tapped her aunty on the shoulder. – Had – dream – last – night, she signed.

– Tell me, signed Ann, with out-loud talking too, though her voice was muffled and low. She’d spent her life talking to her aunty, learning how the sounds worked with their language, not really like Sign—and not really like English.’

We learn Erin’s māmā, Tanea, is dead. We meet Erin’s cousin, Star, in chapter two, back from university, flatting and in pain with toothache despite self medicating. It’s the cousins’ koro’s birthday and they come together at their marae.

‘Erin had a theory that she wasn’t one person. She thought she was a half, with Star being the other half that had wandered off and grown up without her. Except when they were split in two, he received all the parts that drew people in, and she received all the parts that pushed them away.’

Star hasn’t seen his dad, Joseph, for a few years. The discomfort Star feels at the birthday rings true. The disconnection and whakamā of not knowing the waiata, of feeling on the periphery.

‘Star stood idly to the side. He had never been able to fully understand the words, and he’d never really tried. It was something that occupied the room but never seemed to involve him, his life outside the home had taught him that it would soon be his generation that would take the responsibility of keeping the air in the sails. But he was a baby still—he didn’t even own a second pair of pants.’

Erin stows away in Star’s 1994 Daihatsu Mira and they go on a journey back home to their ancestral whenua. Like so many of us, the whānau is fractured by the historical violence of the state. We are shown four generations—Koro; Tanea, Aunty Ann, Aunty Huia, and Aunty Mags; Robbie, Joseph, and Nat; and Nat’s tamariki. The weight Erin and Star both feel is laid out clearly for us in the grief for Tanea’s suicide, whānau responsibilities and relationships. We see it in their moments of frustration, their restless need for connection and impacted mental health. Things are further complicated by the confined, packed space of the tiny vehicle the cousins travel in, which also holds an unnamed stray dog.

‘Wherever she went, the people she loved were falling to pieces and she seemed to make that burden heavier for them. A voice whispered in her ear—shut up, it said, its message echoing in her ear canal and looping on itself, mimicking the ocean.’

Watching this cycle of pain play out is harrowing, but Erin’s grief, which is in everything, has power, and the novel is teeming with compassion. It exposes resistance, a stark resolve to keep fighting in spite of loss.

I was halfway through Poorhara when I met up with Michelle at Kupu Festival. It felt tika that her first book event took place at Ōhinemutu Pa, on Te Arawa whenua, where she is from. It was here that the Fenton Agreement was solidified between Whakaue and the Crown.

The children of the fern sections in the book look back to a pure, pre-colonial time:

‘there was a fertile piece of land – it was once lush

with beautiful greenery – kawakawa tootara raataa

koowhai – the patch was full of birds crickets

weetaa – swarming with life – alas – over time –

this land was encroached on – divided – run over

with heavy cannons – dusted with gunpowder –

only a few plants survived’

Despite the dark subject of the children disappearing into the ngahere (‘one by one they are found by the paapara’), the language and tone sit in stark contrast with the rest of the book, providing a sense of tranquility, showing us the preferred model of existence.

During the kōrero at KUPU, Michelle said, ‘Being Māori is hectic as.’ There was a chorus of agreement from the audience. Erin and Star both feel pulled in multiple directions, and the stories we tell ourselves are really hard to combat as Māori—not to mention the wider national conversation about who we are as Māori. In Poorhara this is brought into focus by characters Erin and Star meet on the road: the Subaru woman, the cop, John the rapist. The current rhetoric around poverty at the hands of the National government—that if someone is poor, it is their own moral failing, and if only they worked harder, they could drag themselves out of it—makes combating these stories even harder.

Both Rūaumoko and Mauī are embedded into the novel, Rūaumoko the restless unborn child a link to the Tarawera Eruption. In the wake of the Tarawera Eruption the Fenton Agreement was not honoured by the Crown. This had devastating consequences for Māori, causing them to lose their livelihood and fall into poverty.

‘The difference between them and Maaui, was that Maaui had a system of protectors, allies—he had people who would tear out their own jawbones, or pluck their own fingernails off, just to see him succeed. Maybe a cousin with a car was enough.’

Laughter and pain are inextricably linked in Poorhara. Erin screams at the Subaru woman, ‘Do you know whose land you’re on?’ and laughter does the same work in a different way. We are living in such dark times. I found myself laughing at things that are true. The dialogue between Erin and Star operates to bring some light in a dark world. This is Rahurahu taking charge of her own history and pushing back. Laughter as resistance, as ownership.

After the talk, I joined Michelle, her Māmā Tui and some of her whānau for morning tea. It struck me that, like Erin in Poorhara, Michelle is an observer. The novel operates on multiple language levels, switching between coda, reo, slang texts and english. The way in which Erin and Star switch between these modes gives them depth, ensuring they are fully immersed in their stories. Sign language is Michelle’s first language. She started signing with her Māmā Tui, (who is Tangata Turi) at three months old. Because Michelle learned English later, she treats it as an outsider language. ‘It had so many rules,’ she said to me at KUPU.

‘eye g0t n0 r3sp3ct 4 da 3nglysh l@ngu@g3’

The Tainui dialect is used throughout, without macrons. Places are largely unnamed throughout the book, a move on Rahurahu’s part to allow the reader to see each place through Erin or Star’s eyes. There are indications of place occasionally, for example when Star and Robbie smoke in the pā.

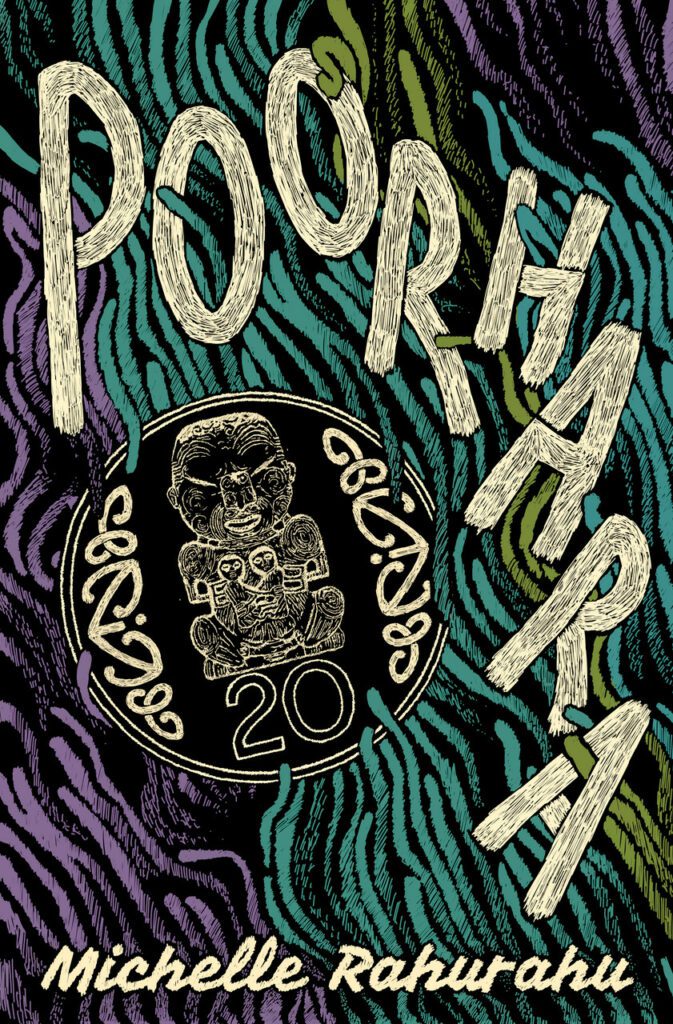

The cover of Poorhara is a twenty-cent coin, printed with an image of a carving. The figure represents Pūkākī, who was an important leader of the Ngāti Whakaue tribe. Michelle tells me, ‘This carving of Puukaki originally sat at a gateway to Ōhinemutu paa and should have been the symbolic gateway into the future but it exchanged hands and was exhibited in the pivotal Te Maaori exhibition across the US due to the popularity of the exhibition. In the 90s, a rendering of the carving was stamped into the 20c coin, the one we know today.’

I finished my cuppa and went out onto the deck overlooking the lake into the sun. There is no reo translation for the word hectic. Colonisation is to blame for hectic Māori lives.

While things don’t work out as hoped—that’s not how trauma works, you carry it with you for a long time—what stands out in the novel is the cousins’ coming together and their whanaukataka. They both make themselves vulnerable with one another, Star when his masturbation is discovered and Erin after the sexual assault. This is a powerful point of connection, in which they both realise it’s okay to be human; to feel like you have failed. Rahurahu imbues a sense of shared relief and hope here, a suggestion of them both grabbing a break.

Rahurahu is a millenial and I’m Gen X, but I experienced the unsettling, valuable feeling of being seen and understood by the writer and the characters, in the feeling like you might lose hold of your anger, craving your dad’s attention, cousins you don’t know that well, the things that are handed down—a pale complexion, a tendency to put themselves in danger, trying to get home. Knowing the waiata and whakatauki mentioned in the novel made me feel happy, because a few years ago I wouldn’t have. This is a feeling that keeps reverberating long after the road trip ends.

Michelle’s friend, the poet essa ranapiri tells me Poorhara is ‘a novel with a poet’s attention and a playwright’s dialogue,’ and after that I can’t stop thinking about what an incredible piece of theatre it would make. Watch this space.

Rahurahu’s instagram has a photo of her standing at Ōhinemutu paa holding the book with this caption:

‘My book bears the likeness of this coin on its cover with the rendering of Puukaki and his whaanau i held it here in the space where the carving sat when it was finally returned to its people, where the descendants like me of Te Arawa have returned we live under the legacy of the Fenton Agreement hara but the tohu of Puukaki endures reminding us of the ways our ancestors tried to hold the pathways forward for us open.

From wood to steel to wood again.’

Poorhara is a search for answers, of finding ways to live in a system not built for you. A longing for home resonates. In the same ways our ancestors tried to hold the pathways forward for us open, Rahurahu is holding the path open.

Emma Hislop (Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha, Kāi Tahu) is a writer living and working in Taranaki. Her first book, Ruin, was published in 2023 with Te Herenga Waka University Press and won the Hubert Church Best First Book of fiction at the 2024 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. Her fiction and non-fiction writing can be found in Headland, The Listener, Metro, Newsroom, The Spinoff, and Pantograph Punch. She was the recipient of a 2024 Arts Foundation Springboard Award. She is currently working on a novel.