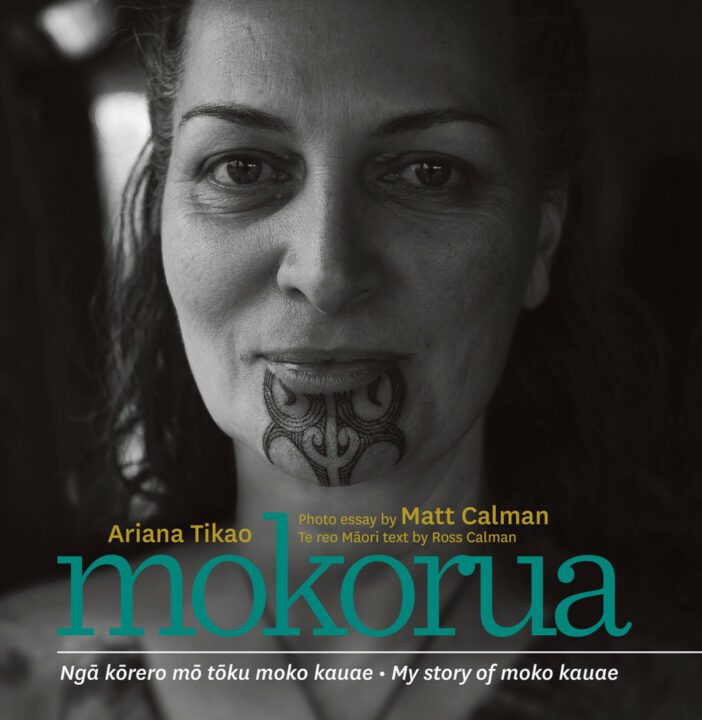

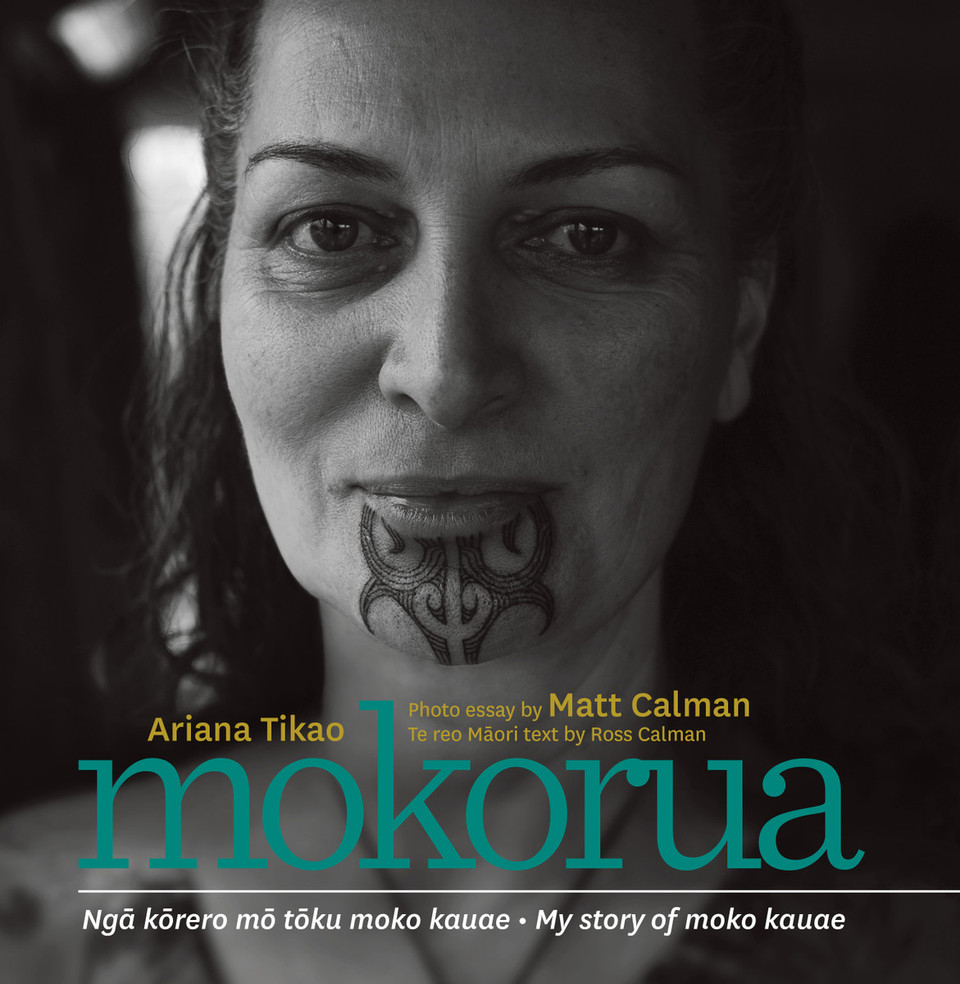

Mokorua: Ngā Kōrero mō tōku moko kauae. My story of moko kauae by Ariana Tikao.

Mokorua: Ngā Kōrero mō tōku moko kauae. My story of moko kauae by Ariana Tikao AUP NZ (2022). RRP: $45.00. Hb, 164 pp. ISBN: 9781869409708 Reviewed by: Siobhan Kahu Tumai.

Sometimes being tangata Māori in te ao Pākehā feels like you have only half the pieces of your life’s puzzle. The more you learn and grow into understanding your whakapapa, the more you wonder what happened to those parts of you that you did not know existed.

Through colonisation our ancestral knowledge has been beaten out of our kaumātua, legislated against, socially stigmatised, and all but lost. It is no wonder that connecting with pictures or stories from books or television can feel like finding secret parts of yourself to rejoice in. These resources are tools of reconnection and can mark the beginning of a journey to understanding yourself more fully.

How lucky are we, then, that the hard mahi of Ariana Tikao, Ross Calman and Matt Calman has culminated in this bilingual autobiographical book that celebrates the rematriation of moko kauae?

In my years as a keen reader of Māori literature, I have not come across such a generous personal account of reclamation offered in both reo Pākehā and reo Māori. ‘Mokorua’ frames moko kauae as a revelation of self, a celebration of reconnection with our ancestral practices and the lamenting of pride in our whakapapa.

Ariana’s face, with her soft features and freshly marked chin, proudly adorns the front of the ‘Mokorua’ hardcover book. She opens with the sharing of a dream she had before she had taken on moko kanohi:

‘I am holding two lizards”, she begins, “…- a bright green male and a paler female. I notice that the female is hapū and I put her in an envelope to take care of her. The male slowly walks up toward my chin.’

I was lucky enough to attend the ‘Mokorua’ launch event at Tūranga Central Library in Ōtautahi. Tohunga Mahina Kingi-Kaui was playing taonga puoro as Ariana read, Christine Harvey gave a quiet kōrero on her practise as tohunga tā moko, Dr. Kelly Tikao (Ariana’s cousin, who’s whare held the ceremony) was generously sharing knowledge and mihi with the crowd, and Matt and Ross Calman offered insights into their journey with the book, Ross (Ariana’s hoa rangatira) as the reo Māori interpreter and Matt (Ross’s cousin) as the kaiwhakaahua.

During Ariana’s kōrero she read the above dream aloud. She continued:

my friend said “that’s your moko”. And then the penny dropped. Moko or mokomoko is a word for lizard in Māori’.

‘Mokorua’ takes us on a journey through Ariana’s childhood, weaving experiences to paint a broader picture of colonisations’ impact on her whānau. Through such narratives as her father being beaten for speaking te reo Māori at school, herself being given a Pākehā name and her mother not wanting Ariana to study Māori at University, we can see the devastating impact of cultural micro and macro oppressions on Māori families over time.

Historic actions such as The Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 and the 1893 Women’s Christian Temperance Union’s (WCTU) “Temperance Pledge” coloured the cultural zeitgeist of the early 1900’s as anti-Māori, including suppressing our taonga tuku iho in favour of learning Pākehā ways of living – also known as assimilation.

The outcome of the near successful assimilative practises of early 1900’s is reflected in the way Ariana writes about how moko kauae was a scarce sight in the 70’s and 80’s, a relic of the past seen in old photos or media.

In “Some reflections on Māori Women and Women’s Suffrage”, Leonie Pīhama (2018) talks about the hardships our tūpuna wāhine who fought for women’s rights to vote faced. When discussing “The Temperance Pledge” Pīhama states:

‘Where gaining the vote was… considered a victory, the involvement of Māori women in the WCTU was not completely beneficial.’

Our Māori women were faced with the expectation that they must give up certain traditional practices in order for that right to vote. If they did not adhere to the following pledge they would not be able to be a part of Ngā Komiti Wahine within the WCTU.

.

“The Temperence Pledge” was worded as follows:

He whakaae tēnei nāku kia kaua ahau e kai tūpeka, e inu rānei i tētahi mea e haurangi ai te tangata, kia kaua hoki ahau e whakaae ki te tā moko. Mā te Atua ahau e āwhina.I agree by this pledge, not to smoke tobacco, not to drink any beverages that are intoxicating, and also not to take the tā moko. May God help me.’ (Pīhama, 2018)

When your people and cultural practices are publicly subjugated for centuries, it is difficult to step outside of the norm if that’s all you’ve ever known. While our ancestors were photographed and painted with moko kanohi, our parents and grandparents grew up in a time where people were punished for it, if not corporeally, then socially. The flow on effect is silence; little to no stories being passed on and little to no traditions being celebrated in fear of the next generation being treated like were.

Ngāhuia Murphy in ‘He Awa Atua’, relays taonga tuku iho from “Aunty Te Wai” in Te Urewera about pre-colonial menstrual traditions – when kōtiro had their first menstruation they would take on a new name and have the first parts of their kauae etched into their chin as a rite of passage. It was a birthright, a becoming, and one that had been lost through those far reaching effects of colonisation.

The silencing and suppression of our practises has met its match in contemporary wāhine like Ariana. She shares her experience with Aoraki Bound in which she experienced ‘walking in my ancestors footsteps…’. Facing her ancestral mauka Aoraki raised thoughts of her responsibilities as she ages.

‘Losing my parents has made me think more about the legacy that I wish to leave behind. If I have mokopuna in the future, what kind of world do I want them to be born into?’

Due to the hard work of wāhine like Ngāhuia Murphy and Leonie Pīhama, we have seen a noticeable uptick in recent years of many tangata whenua, in Aotearoa and other indigenous folks from around the world, reclaiming their indigenous markings. As Ariana notes:

‘..moko is no longer something relegated to a distant and foggy past. It is here and now – proudly displayed as a market of identity in a country very different to the one I knew as a child.’

In ‘Mokorua’ Ariana offers us a contemporary version of this rite. She shows us parallel connections between the collective revitalisation of her iwi, Kāi Tahu, and hapū tikaka and taoka after the ravages of colonisation, and the reclamation of her taha Māori in te ao hurihuri, culminating in the revealing of her moko kauae.

Equally important is Matt Calman’s photography which gifts us vignettes into the intimate space Ariana’s moko kauae ceremony held. Through a collection of black and white and colourised photographs, we are allowed glimpses into the mokopapa itself. It is fitting that almost half of the book has been dedicated to this photography collection as sometimes images are the closest you can get to conveying the mana and immensity of moments like Ariana’s ceremony.

Whanau and friends feature in wonderfully lit pictures in Dr. Kelly Tikao’s whare. On-lookers staring intently at the tohunga, Christine, leant over Ariana, with tears in their eyes, pride and adoration softening the edges of their features. Hands are held, wāhine mau moko and whānau are seated around the room, and Ariana’s chin is being adorned with the stories and lineage of her whakapapa.

One of the most emotion evoking images, in my opinion, is a black and white two page photo in which multiple people’s hands lovingly grip Ariana’s legs and feet. The central arm of one of the people has a tā moko, their hand planted upon Ariana’s shin, firm yet supportive in its placement. You can see that the connection between them and Ariana has divine intention, a spiritual and physical convergence of belief and pride. It evokes the depth of their belief in our tikanga of moko kanohi. You can see that this is a whānau occasion and that it is their role, as whānau, to hold her through it.

As I received my kauae by the same kaitā, Christine Harvey, I also had my friends and whānau holding my physical body. Through karakia, singing and meditation, those hands held me from spiritually floating away. When your kauae is being etched into your skin there is a delicious hot pain that you must endure. Ariana likens the pain to childbirth, like pushing through the searing heat of tearing flesh, giving birth to a new person and continuing our whakapapa.

In a way, that’s what we are doing when we lie in front of the tohunga and expose our face to their marking tools – giving birth to a new person. From that day forward we walk through the world as a reminder of who we are and where we come from. Moko kanohi is a physical manifestation of all that our people have kept in the face of colonisation, and as a tohu from our ancestors to those who are still on their journey, that this is a vital piece of ourselves as Māori.

The last picture in the book is a portrait of Ariana and her daughter, Ariana’s moko kauae and her daughter’s tā moko on her arm still fresh. The continuation of whakapapa is central to our identity as Māori, so it makes sense that Ariana would end ‘Mokorua’ with her uri by her side continuing our traditional markings. Ariana ends her acknowledgements by looking toward the future of moko kauae:

It is a realisation of taoka tuku iho, derived from whakapapa, and laying the foundation for all the mokopuna yet to come.’