The Art of Michael Armstrong

By Andrew Paul Wood

Michael Armstrong was born in Christchurch in 1954 and has regularly exhibited since 1969. He graduated from the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts in 1976. He lives in Timaru in South Canterbury and had a lengthy career as an art tutor at Aoraki Polytechnic, later Ara Institute. He was the University of Otago’s Francis Hodgkins Fellow in 1984 and received a CSA Guthrey Travel Award in 1990. Armstrong’s work is characterised by a contrarian singularity, simultaneously accessible and yet opaque with allusions. Far from a flashy show of erudition, it is, in fact, a kind of humanist remembering with love and devotion.

The 1970s saw a change in contemporary art in Aotearoa, or rather a consensus of sorts. Armstrong graduated just as the growth of national art awards and professional dealer galleries made an art career seem like a viable option. In Canterbury, as elsewhere, the flowering of commercial graphic art also had an influence on younger painters and printmakers, giving them new insights into the way figurative imagery, pattern and text could, in combination, convey strong, cohesive messages. Pop art arrived late in New Zealand, but the potential was there. When the Robert McDougall Art Gallery (now Christchurch Art Gallery) put on the exhibition 40 out of 40: Canterbury Painters 1958-1998, then curator Neil Roberts grouped Armstrong with others of this cohort: Jeffery Harris, Bill Hammond, Martin Witworth, Paul Johns, Sam Mahon, Helm Ruifrock, Kees Bruin, and Michael Thomas.

Armstrong is both painter and sculptor, and his work has a striking anarchic energy combining expressive figuration and line, and vibrant colour. This rich synthesis of formal diversity, volatile composition, and spontaneity is deeply life affirming and humanistic, and has characterised his work for the last five decades. This remains a continuous, anchoring thread throughout all phases of his ongoing exploration of form and meaning. In painting Armstrong displays a technically fluid command of a variety of styles imbedded in a push-pull interplay of decorative surface and illusory depth.

This dynamic tension segues via Frank Stella-esque shaped or rough-edged and unstretched canvases into Armstrong’s sculptural practice, evolving from late modernism in a pop palette into post-painterly abstraction. This may also reflect the general influence of Constructivism in Canterbury scene, both in the art of Don Peebles and the architecture of Sir Miles Warren, Peter Bevan, and Paul Pascoe. Artist Philippa Blair, another product of the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts, was also exploring similar territory at the time.

‘I came across Stella after I had already started to play in 3D painting,’says Armstrong, ‘but he certainly had a great influence. I was more interested in painting in 3D, which was often dismissed as decoration. 3D painting had many ramifications on meaning, from spiritual layering and the unseen, to the logical, where rather than the illusion of 3D, those works just took the idea literally.’

Visually it stands alone, but the formation of style cannot be entirely separated from geographical context. There are deep roots in the European neo-expressionism tradition associated with the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts – Rudolf Gopas, Philip Clairmont, Allen Maddox, Tony Fomison, Philip Trusttum – which, while supplying a strongly motivating vigour, has long since transmuted into a postmodern eclecticism.

‘I was taught by Gopas,’ says Armstrong, ‘and Phil Trusttum was an early influence. After that I looked to Australia, Peter Booth for instance. Australia had a much more positive attitude towards painting and expressionism, so I tended to look there rather than the strong conceptual, sculptural emphasis here. Gopas was well past his most influential by the time I was at art school. He was very unwell. He was more conceptual in his own way, and, after he left the institution, he got into being a performance poet.’

Of greater influence at Canterbury was painting tutor Quentin MacFarlane, and the theoretical concepts introduced by Ted Bracey. There is a great deal of MacFarlane’s oceanic colour fields and Bracey’s jazzy quasi-cubism in the way Armstrong composes his paintings, but Bracey also brought an interest in the post-painterly and postmodern eclecticism. ‘Although I have always enjoyed those new art forms when I see them,’ says Armstrong, ‘painting did get it in the neck 30 years ago. Conceptual art has a strong personal expression at its core, as did postmodernism. I did look closely at the theories inherent in postmodernism.’

After this, Armstrong lived in Dunedin for a time, finding great stimulation in its vibrant cultural milieu. ‘The arts community was hugely lively then,’ he says, ‘Andrew Drummond, Ralph Hotere and particularly the developing ideas of Jeffrey Harris. Also, Kobi Bosshard, the silversmith, and his disciplined thinking. Bosshard was a role model. He played with 3D sculpture as well, colour. In those years – 1976 through 1979 – learning colour theory was important to my work.’

Armstrong absorbs as he goes. The lived experience even takes precedence over the theoretical. He learns from what is around him and works in that space that Robert Rauschenberg called ‘the gap between art and life’. In relation to an exhibition of his work at Christchurch’s Robert McDougall Gallery in 1985, he wrote at the time:

‘I do not see my art as being separate from my life, or that it is an activity that needs the protection of silence. I work through different levels of my conscious and unconscious varying between immediate hedonism and emotion to a delayed reaction and detached analysis of events and situations and of how to express these as ideas. To use the terminology, I work in an abstract expressionistic manner, the use of paint conveying the attitude to life.’ [‘Michael Armstrong Artists Project’, Bulletin, No.38, March/April 1985, p.1]

Life dictates response in form and colour, of which those 3D canvases were an important transitional phase, establishing an entire philosophy to the artist’s process of making. The act of making becomes a poetic gesture, a quasi-divine act of creation imposing order and logos on the formless void:

‘The canvas hangs loosely, has its own properties. It expresses itself. The edge, cut roughly, implies relationship both to the inner shape, and to the outer, surrounding space, that the canvas is part of a real cosmos not isolating the painting within rigid structuring. The paint is as an event, something that happened across the surface of the canvas, forms created, and ideas expressed, the balance between order and chaos, in the human striving to create order out of chaos, figures and gestures overlap, replace each other, within an abstract chaotic energetic cosmos. The canvas continues on both sides, part of an infinity that folds over itself, revealing only part.’ [‘Michael Armstrong Artists Project’, Bulletin, No.38, March/April 1985, p.1]

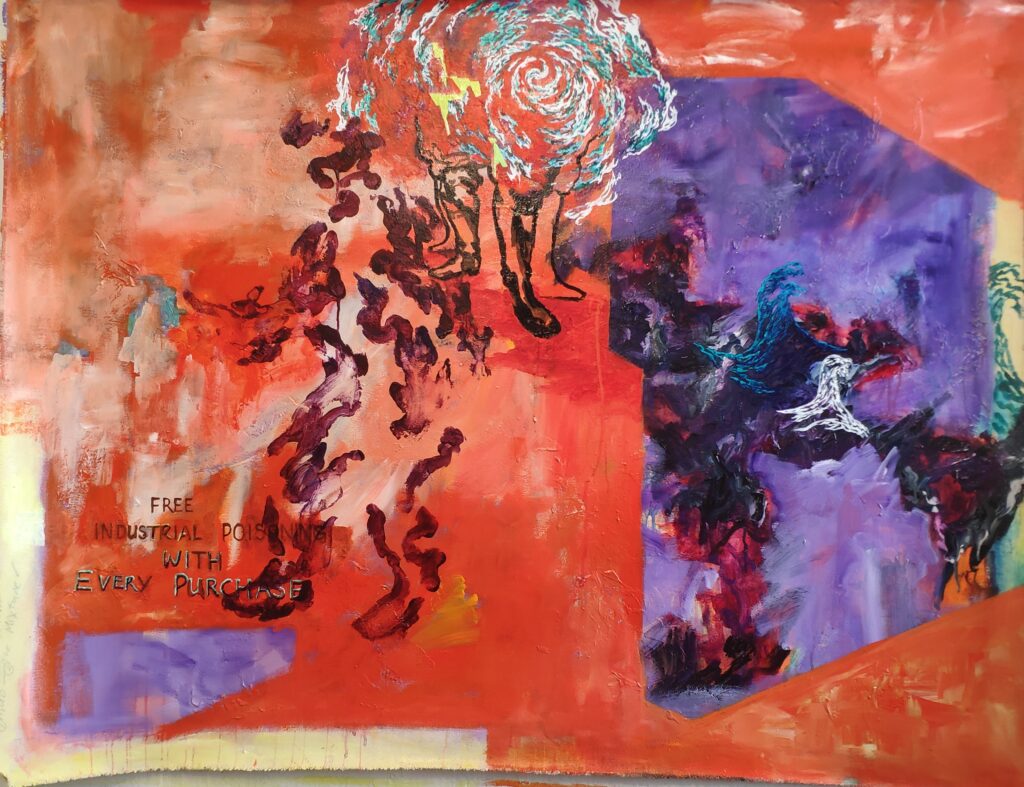

While the paintings, for example, have a clear emphasis on their existence as objects and their haecceity, they are also concrete records of inscape and emotional life in the moment. Art is a way of life and Armstrong’s art is full of therapeutic catharsis and humour, but not at the expense of aesthetic analytical logic. That said, there is an objective awareness of the Anthropocene world that permeates Armstrong’s more recent work with a wryly ironic, apocalyptic sensibility. Environmental and social concerns emerge to the fore.

Armstrong’s 2017 exhibition Preaching to the Disconcerted, which showed at the Central Gallery in Christchurch, blended cartoonish renderings of Hokusai’s wave with disembodied limbs, and spermatozoic splatters of white in turbulent fields of colour as a rallying cry around climate change, ecological collapse, and civil unrest. This finds a curious frisson with the artist’s delight in the cartoonish grotesque and human psychodrama. This sensibility animates the masks and stage elements he designed for a production of Aristophanes’ Clouds in 2019. Here a puckish irreverence creeps out, with hints of Gerald Scarfe.

This eclecticism is one of Armstrong’s greatest strengths, the ability to draw on so many sources across so many media and handle them all confidently and well. This mainlines directly into the urgency of the artist’s message and concerns which grow more urgent every passing day. He is refining a kind of history painting that seeks to make sense of the seemingly arbitrary, the fragmented and tempestuous fabric of the modern world. These are anxious times inching ever closer to total existential collapse.

‘My realization today,’ says Armstrong, ‘is that, in my current work, any particular work may be finished in one of several different manners. The works begin and develop as broadly handled colour abstractions, but according to my own mood, determination, or vagary, may end by being solved in one of several modes. Of staying as an abstract, another of being people by figures, mobs, and rioters, of becoming an apocalyptic seascape, or of an architectural projection of a sort. All hint at a climate change apocalypse and the different potential responses or outcomes, from scenes devoid of life, to scenes where humans are responding as unpredictable and unmanageable humans. This is not a conceptual game on my part, but my painterly response to the issues we face.’

Armstrong’s most recent work is just as political as it ever was, expressed through the imagery, but also, to an extent, his process, the flow. He says, in a Joycean flow of consciousness not dissimilar to how he works:

‘The isolated and severely eroded individual figure, or figures where they walk in two directions at once, but who dissolve into fluidity. Images of rioters, the mob. The mob, who figure large in history. Watch out, Coriolanus. Mind your neck, Robespierre. It might look unconsidered, but each gesture of these works is contemplated, debated, justified. So firstly, I draw, a great deal of crayon, ink, charcoal. The canvas is prepared, I create the background, chaos, try to challenge my own sense of order, but that is an impossibility. Well, it’s a painterly version of chaos, so it is carefully controlled, and composed. The colour range is also very thought through. I do like the critical terms that have been used about my work in the past, “lurid daubs” being my favourite currently. Draw the viewer in, then reveal to them, and to an extent undermine their pleasure maybe.

‘The central figure reflects my interest in eastern calligraphy, a figure who is expressed in a few seemingly quick strokes, and often takes several attempts until it looks casual enough. Anonymous, maybe only identifiable as a figure from the clue of a pair of feet at the lower end. That central figure imagines it is bigger and more important, that its consciousness is more important than the other, smaller figures who run past, around, in front of it. Based on the Tympanum Sculptures of Gothic Cathedrals, where everyone is graded in size according to relative importance. The central figure is almost transitory in some senses, and I often rub or wash sections of the painting away completely if I am not satisfied. These paintings do take time. And yet I feel an absolute urgency, as I have all my adult life, existentially. The wave is eastern too, not actually Hokusai’s, but I do also like the concept of being able to endlessly repeat the wave, as waves are, and like a craftsperson who repeats the same motif endlessly. And the waves keep coming.’

Even so, Armstrong’s colourism and formal frivolity suggest a hope for humanity that hasn’t entirely been extinguished. It is impossible to love colour and not have an element of optimism in the soul. One cannot be a humanist and not still have hope. I spoke to the artist again on 11 November 2023, Armistice day. He decided this was appropriate in the discussion of his work, or perhaps inappropriate, saying:

‘The human creature is at war with itself it seems, not just in battlefields, but determined to compete and destroy each other in so many ways, unable to overcome our own perversity of nature, our seeming inability to share or to behave fairly. Capitalism is not the friend of democracy of course, but finds much more in common with fascism, the rule of a minority of rich people and their enforcers. Democracy can control capitalism to some extent, ameliorate the effects, the worst effects, but democracy and capitalism are strange bedfellows, I think. Today, as I painted, I thought to myself, deluded maybe, about how on one hand I do enjoy not having to worry myself about showing my work or selling it, and yet thoroughly enjoying doing both. I’m a good capitalist.’

About six months ago I myself moved permanently back to Timaru, and it seemed appropriate to consider how the conditions in that South Canterbury service town affects the creative process, being semi-close to and semi-far from Christchurch and Dunedin.

‘I do feel,’ says Armstong, ‘that the isolation from markets works for me. I do love the joke about the art dealer who said he preferred his artists cold. They can have me served cold. Hopefully any possible survivors by that time can find a use for my big paintings as tents or ground sheets. It’s that feeling that some artists had before the second world war of impending doom, all the while others talk up the economy, productivity, GDP, and ultimately their profit margin. I’m not hard up either, another part of the puzzle, I can afford to paint and not worry about selling. Is that too much truth? Painting though as a means of spreading a message, even if it’s secondhand, on Facebook, the imminent danger, the happening event. Virtue signalling? No, I do try to live it, but it’s an illusion, because without the current system I would be very quickly dead, run out of the things I need to survive. I consume more than my fair share, burning carbon, spreading plastic waste. Mea culpa, so crucify me. Not that I am religious or bear any comparison with the figure of Christ.’

Timaru actually possesses a fairly robust local art community in what Armstrong sarcastically calls ‘this Tory paradise.’ For all that it’s relatively small, insular, solipsistic, and materialistic, there are, Armstrong says, ‘people here who realize how hard it can be, and I think it could bear some comparison to the monks of Skellig Michael or Iona, last bastions of Christianity against the hordes.’ But not everyone cares about culture: ‘There are other people here who can’t see the point of art or see why anyone would ever want to make art, as if it was a bad or embarrassing habit. But by and large, who cares? Plenty of people, the considerable minority who would go to art school if it was available, (best if it was free), or study modern American literature, or the ancient Regime, music, play in a band. Capitalism does its best to dissuade that delusion.’

The American artist Robert Rauschenberg used to say that he worked in ‘the gap between art and life’. With Armstrong I’m not sure there’s a gap. The two just seem to meet at an invisible horizon like the sea and sky. Sometimes sea and sky are visibly different, sometimes not.

‘Often, halfway through a painting,’ says Armstrong, ‘I see a new idea, and overpaint the canvas, using the painting underneath, still able to be seen but through a new layer over the top. There is a risk that it all appears illogical, but that is human. Painting, art, creativity add meaning to life. I could find some other form of gratification, shopping maybe. Making money keeps plenty of people well occupied; the rich thinking about how to keep it and how to distract attention from their acquisitiveness, the poor in finding a little bit more. The rich in using their wealth to creating distracting political content to turn the mob, the poor about finding the cash to get petrol to get to work. Consumerism fills a spiritual vacuum, which is fine for the capitalist profiteers. Do I need a new car, where shall I go to next in the aeroplane, is my house good enough? (No, I’m obviously an art snob, an elitist.) We are on the treadmill; we are all together on a dirty old bus, belching smoke. Really, it’s just a reason to paint. Even the paint is toxic enough, especially if you burn it. Don’t burn the paintings, use them as temporary shelter.’

Note: an earlier version of this essay appears at Michael Armstrong – Chambers Art Gallery.

Michael Armstrong is a multi-award winning painter and sculptor. He held the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship at the University of Otago in 1984. He has worked as an artist continuously for forty-five years, exhibiting nationally and internationally. He was an art lecturer and post-graduate supervisor at the art department at Ara, the main public tertiary institution in Timaru, working there for twenty-six years. He is well respected nationally for his drawing, painting and sculpture, and his work is held in many important national and public collections.

Andrew Paul Wood is a Timaru-based independent cultural historian and commentator, art writer, book reviewer, essayist, translator and poet. He writes for a number of prominent publications in Aotearoa and Australia. He was the co-editor and translator with Friedrich Voit of the collection Karl Wolfskehl: Drei Welten, Three Worlds (Cold Hub Press 2016), Dunediniad: A Psychogeographical Ode (Kilmog Press 2018) and The Sonnets of Walter Benjamin (Kilmog Press 2020). His latest book is Shadow Worlds: A History of the Occult and Esoteric in New Zealand (Massey University Press 2023).