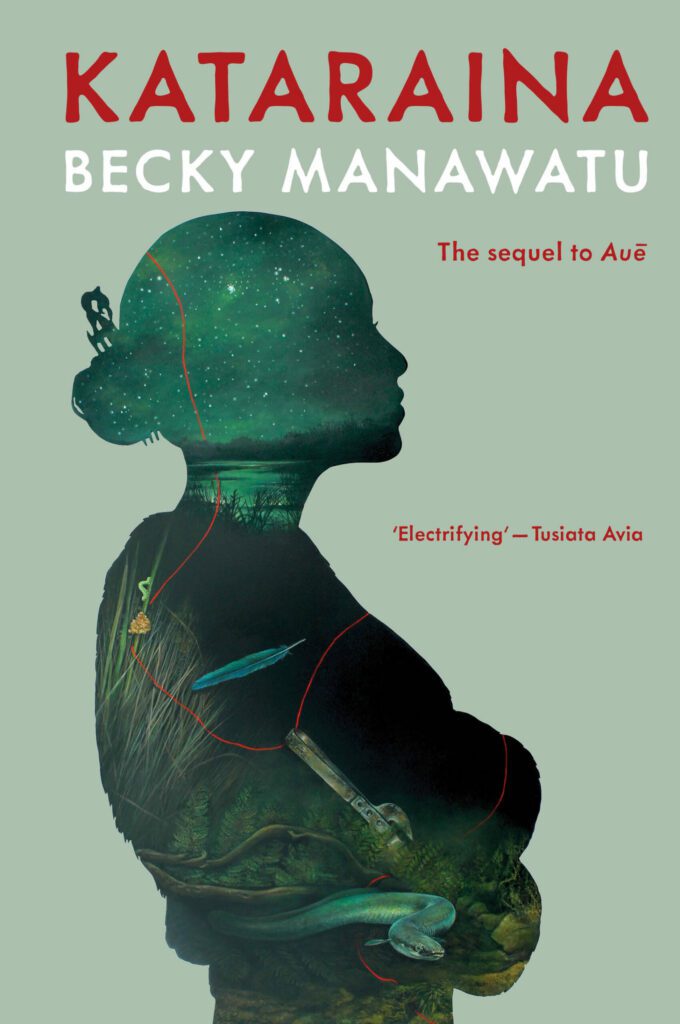

Kataraina

Kataraina by Becky Manawatu. Mākaro Press (2024). RRP: $37.00. PB, 284pp. ISBN: 9781067011307. Reviewed by Jack Remiel Cottrell.

Kataraina is the follow up to the acclaimed Auē by Becky Manawatu, but it would be a bit of a misnomer to call it a sequel. Or a prequel, to be honest. Kataraina is something of a companion to Auē with the story taking place after, alongside, and before the events of the previous novel.

The timing matters to this book. Each chapter of Kataraina’s (Kat) story is marked by its temporal proximity to when ‘the girl shot the man’—three months before, two years after, 128 years before, the moment of. The only exceptions are chapters set in January 2020, when Cairo comes to her whenua as part of a research team, who end up finding a body.

But whose body? When? What relation does this death have to the swamp which lurks in the background of Kat’s life? Many mysteries, small and large, are obscured by the jumps in time, the shifts in perspective, and the inclusion of the research team. I spent a lot of time flipping back and forth in the book as I read, trying to pin down what was happening to whom and when.

Through the perspective of ‘we’—the Te Au whānau—the reader begins to understand the forces at play in Kat’s life. Her parents, her older siblings, the complicated relationship between her and her grandparents. Most of all, we understand the shifting relationship Kat has with herself, split into four: Kat, Mess-Kat, Swamp-Kat, and City-Kat. These arrive in her dreams and in the coma where she spent much of Auē, and the parts of her which are most deeply connected to her whenua and her tīpuna are the parts which feel rather than which think. The swamp is the constant presence, a force that pulls on Kat and the other characters, a symbol of the resilience of wāhine in the face of men’s violence.

The looming threat of violence lurks throughout the book—and not just in the chapter headings and the sections of story that unfold into the tale of a wahine killing a Crown surveyor. In a book full of harsh and unromanticised depictions of domestic violence, one part that really stood out to me was the emotional abuse, Stu leashing Kat to him even when she had friends and family around.

‘Though he needed her help, the cream he liked to skim off the top was very precious to him: her waiting. Waiting in the kitchen for him. Her sitting there wondering. Each morning he’d tell her a job he needed help with, and she’d ask, “What time you reckon?” And he’d shrug. “Depends.”’

Through the delicate teasing apart of the narrative, Manawatu shows the braided tapestry of time which brings Kat to the point where the girl shot the man, and then through—the defining moment of her life which begins to define her less and less.

Kataraina is… a lot. In the hands of a less talented writer, the fractured timelines and narratives would be intensely frustrating. But Manawatu’s skill with words gives the reader a through-line, presenting a beautiful thread that calls on the reader to follow it, and by the end, to understand.

Jack Remiel Cottrell (Ngāti Rangi) is a short fiction writer with an expensive rugby refereeing habit living in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. His debut flash fiction collection Ten Acceptable Acts of Arson and other very short stories was published in 2021 by Canterbury University Press.