Island Notes: Finding my place on Aotea Great Barrier Island

Island Notes: Finding my place on Aotea Great Barrier Island

written by Tim Higham, illustrated by Harry Higham.

Wellington: Cuba press (2021).

RRP: $38.00. Pb, 162 pp.

ISBN: 978-1-98-859540-5.

Reviewed by: M Oliver

“I am not here to work on this island. It is here to work on me.”

(Talking to trees, p. 134)

The ‘work’ of the Aotea Great Barrier Island transpires through the writing of Tim Higham, an award-winning science writer and environmentalist. Here, Higham takes the role of an intermediate, uncovering the island’s mystery, power and beauty through the subtly written and designed Island Notes.

The notes are a poetic meditation on our contemporary relationship with nature, the cosmos, other humans and ourselves. In flash-fiction-like miniatures, braided into chapters, the author lets his curiosity wander about the wilderness. Entropy, connection, change, loss, development, coexistence and belonging – all inevitably inherent to nature, and humanity

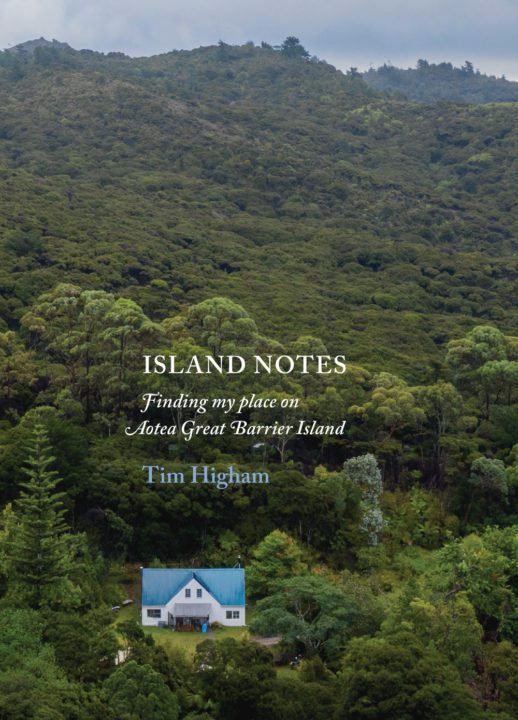

The book shatters the idealistic view of property, in the wild and off-grid; it is a dream and a nightmare. The purchased house, with its racks and leaks,“drifts towards chaos”.

(Home, p. 15)

It is a “lesson in entropy and a testing of the bounds of marriage.”

(Home, p. 16)

And it prompts a reconsideration of the author’s relationships. The connection with nature becomes a distiller for human relationship itself.

Despite its fragmented form, there is a story line, though it is deeply seamed under such richly layered strata. There is a home, a house, a pivotal point. From there, the topography of Notes grows. Branching out across the bush; the ridge, over the island, to the sea, the reef, the dark sky, and beyond into the universe. A sense of place is underlined, and a sense of time passing and change. Narrative travels back in flash memoirs, illustrating what brought the author to the island: from his parents’ appreciation of nature, and his early boyhood in Taranaki, through his study, work and travel. Around the world in search of a tipi, and of environmental justice, all the way down south to Antarctica and back up again, to Aotea. A “place where horses remain unbroken”.

(Home, p. 21)

The island lets time disappear too. It lets things be, sit silently. It invites a pause, and provides time to “curate the interior world”.

(Back & forth, p. 86)

A lot of time is spent in the sea, and in the bush – naming the fish, the birds, the trees. The insights into life cycles – human, animal and floral – are woven into the narrative with sensitivity and sophistication.

Notes are carefully shaped. Images are refined and distilled, not so much through the scientific eye as through the stillness of the mind and soul. Each sentence strokes the land, outlines its beauty. Life is both noticed and noted, human agency is at a remove. All that happens is part of something larger – universal. Facts and poetry coexist on the page.

The juxtaposition of the images, observations and reflections is powerful and poignant. Rich with alliteration and analogy; lines echoing the language and colour palette of the island, its bird song, and sea song, its hues of green and blue. Like the leaky house, form is fractured, leaving cracks and gaps. No answers are offered. We are simply left to pause and wonder.

The book itself is neatly designed from the front cover to the back. With Harry’s sketches and fine fonts, the house and family photos, and references in homage to influential nature writers, making a well-balanced artifact, and one that rests peacefully in the hand.

Twice read and thrice noted, I can’t wait to pass it on to my friends.