Industrial Camouflage [The Chaos of Hope]

![Industrial Camouflage [The Chaos of Hope]](https://www.takahe.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/T108-cover-ruff-545x720.jpg)

By Claire Chamberlain

Sefton Rani describes himself as a maker who uses paint as his material of choice to create contemporary Pacific art.

Rani produces work that exists outside hackneyed tropes of palm tree-fringed sunsets or other touristic motifs, yet still holds strong connection with the art, history and spirituality of the southernmost of the Cook Islands, Mangaia. Rani’s father, Rikado Mii Rani, left Mangaia in 1960 to work in the industrial paint factories of Auckland and never went back.

The physical act of art making provides Rani an opportunity to think about his ‘Pacificness’. He explains:

Making gives me an opportunity to think. To think about heritage arts, think about my place in that lineage, how I feel the ancestors watching, how I strive to extend what Pacific art is. [It] gives me a reason to research history … which is my way into understanding what it is to be an urban Polynesian as the information of the past was not handed down.

In his recent exhibition, ‘Industrial Camouflage [The Chaos of Hope]’, the last one to be shown at the now closed Scott Lawrie Gallery, Rani was forced to pivot to produce a body of work that nearly did not get made, or rather, was made almost entirely again.

Rani and wife Kirsten lost their home on the apocalyptic night that Cyclone Gabrielle devastated Piha, their small community on Auckland’s west coast. Slips destroyed houses, blocked roads and torrential rain caused flooding. Rani’s studio and all the work he had accumulated and almost all the paint skin material he had been making over the previous 12 months before the cyclone hit were also gone.

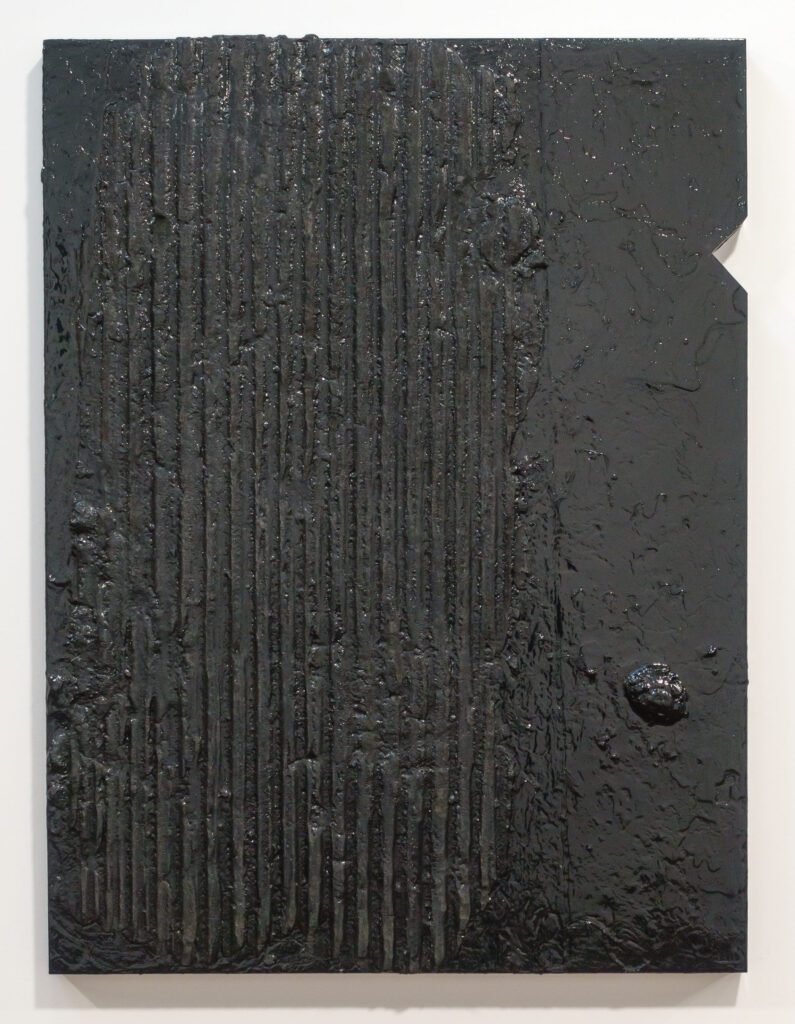

The works that make up the exhibition predominantly respond to the night and immediate aftermath of this cyclone experience. There’s a Hotere-like darkness to the works into which Rani has sunk text into paint coagulated with black iron sand collected from Piha.

While Rani took art all through secondary school and was always drawing (as his father did) and making through childhood, his teacher told him he wasn’t good enough for art school. Art in the 80s at Kelston Boys and elsewhere at the time meant Kandinsky and the high priests of European or American modernism—certainly not anyone ‘Polynesian’, except if they were a … perhaps a “primitivist” influence on Picasso or Brancusi.

After leaving school with two ‘B’ Bursaries gained in consecutive years, Rani started at the bottom of the hotel industry as a bellboy. A highly successful 25-year career eventuated where he became a hotel IT guru and something of a travelling Mr Fix-It who opened hotels across the globe. He had stints in Sydney, New York, Hong Kong, Shanghai and most of the major cities of the world, where he always visited public and commercial galleries.

It is perhaps this formative international experience, and his particular interest in the marriage of painting and sculpture, that has led him to be most responsive to global contemporary artists like Anselm Kiefer, Christopher Wool, Rachel Whiteread, Theaster Gates, Sterling Ruby and particularly Mark Bradford.

Like Bradford, Rani is self-taught and only made the decision to leave the corporate world for an art practice 10 years ago. He has brought to bear his rigorous work ethic, charisma and intellect to all aspects of his practice since, and has even recently made the Listener’s top 100 list: New Zealand’s most intriguing people as part of the Visual Arts line-up. [1]

He is deeply interested in the Italian Arte Povera movement as well as the Japanese concept of wabi sabi which both place emphasis on imperfection. Rani saw Lawrence Carroll’s work exhibited in Auckland saying that ‘it was definitely something that made me have a hard look and made me think about the whole Arte Povera movement.’ More recently, late in 2022, the artist saw Bradford’s Pickett’s Charge at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC. Bradford’s conflation of abstract painting with the social and political realities of today was profoundly influential.

The works in ‘Industrial Camouflage [The Chaos of Hope]’ are all paintings, but they bely this at first glance. They also bely any obvious connection to a Pasifika art tradition, and, rather, their minimally coloured, striated and pocked surfaces have more in common with the sculptural assemblages of discarded materials made by the NZ born Aussie sculptor Rosalie Gascoigne.

There is certainly a similarity to Gascoigne’s work in the patina that Rani creates once the often 20 to 30 layers of paint are met with the acid bite of chemicals or abraded with power tools or combusted with flame. Hers are found that way however. Rani says of his process, ‘a heater is okay, but takes too long. A gas torch, mega heat gun … and a mask is the go.’

Sefton Rani, The Questions Are Not Amusing But Tragic, 2023. Image © Sait Akkirman

The paintings’ surfaces are left scuffed, scarred and, sometimes then, sawn or incised. In his abrading of paint, Rani also takes a walk on the wild side with the street art gang of Brassaï, Dubuffet and Cy Twombly. The surfaces communicate, in this exhibition, the destruction caused overnight by Cyclone Gabrielle.

Rani also made a connection to his Cook Island heritage in the physical experience of the exhibition. A Mangaian adze which he had recently bought at auction was positioned on a plinth by the gallery door. It was the first thing you encountered and it functioned like a sentinel or perhaps a form of rosetta stone decoding some of the layers of meaning that wrap the 25 works in ‘Industrial Camouflage’.

Such adzes like the one Rani owns were distinct to anything else in the Pacific. They were characteristically lashed with braided coconut fibre to finely decorated and carved shafts that functioned rather like a plinth. The shaft was typically architectonic and turret-like in its form and pierced with square holes and triangular patterns, including double-K shaped motifs. [2]

The double-K motif found on Mangaian adzes represents two brothers Raumea and Te Uanuku who went into battle back to back with rope tied around their waists so they could not be attacked from behind, or if one fell, the other could hold him up. The form of the double-K represents them back to back with their limbs outstretched. This motif also expresses the solidarity Rani finds in the wider Pacific community and in the posse of Pasifika artists who provide support to one another.

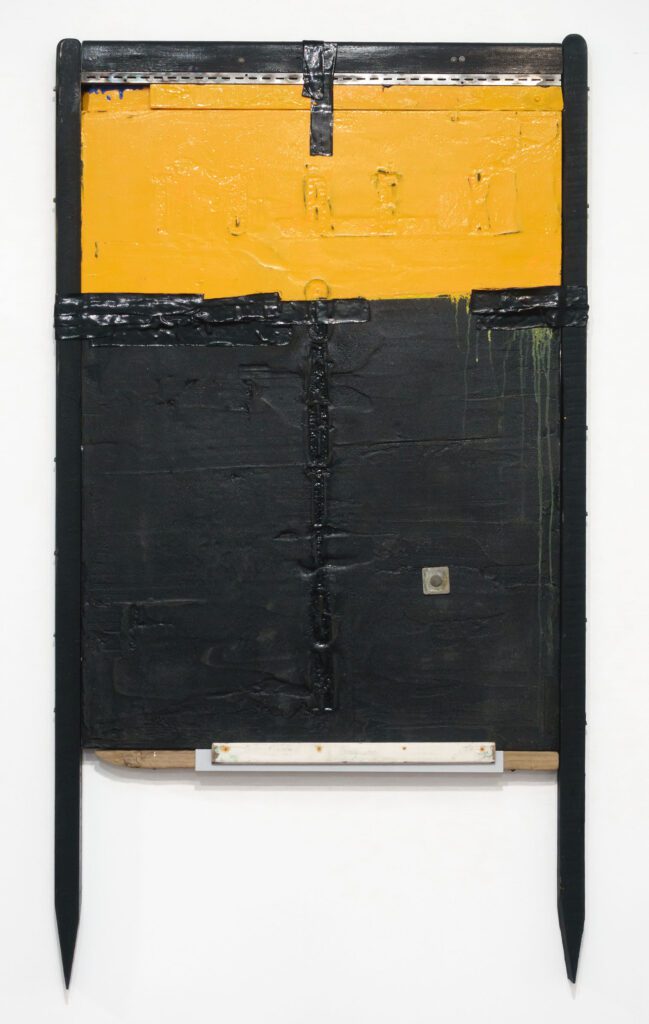

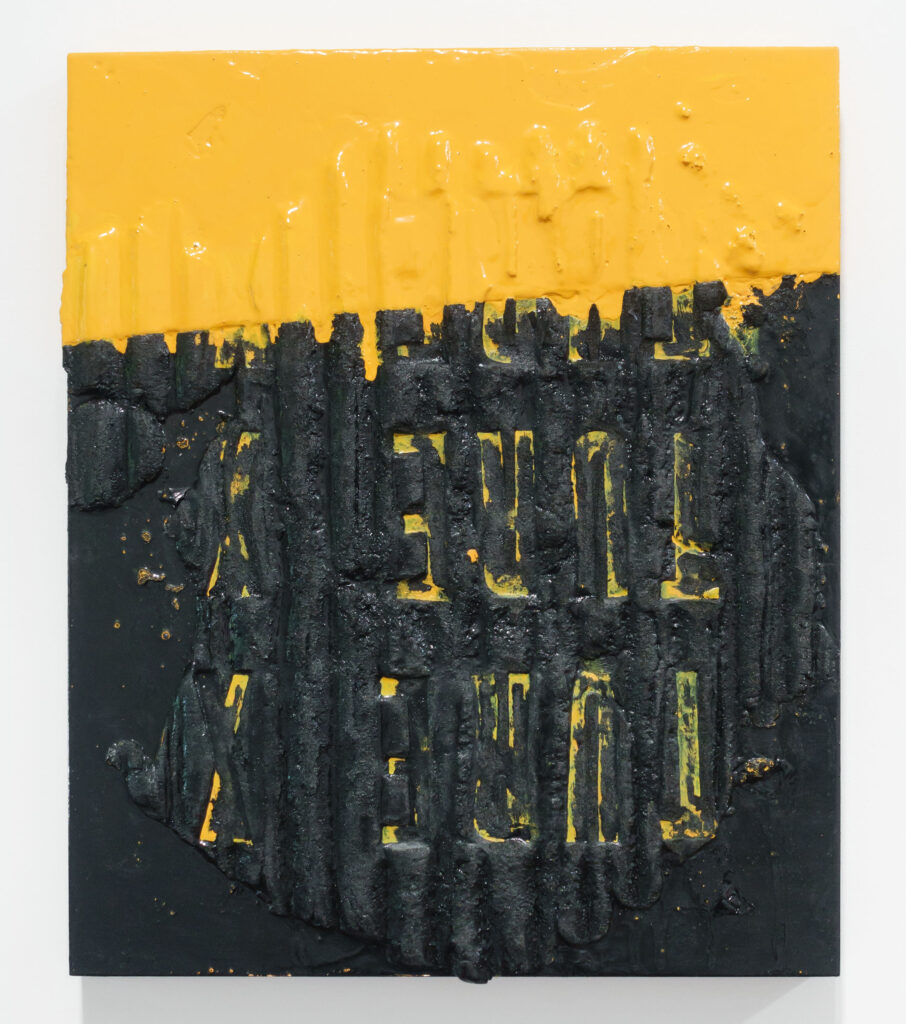

We Collide Together was a key work of the exhibition. Here a real estate sign found by the Piha roadside (the artist appreciates such ironies) is collaged together with other retrieved detritus, such as strips of metal and wood. It is then coated with thick layers of yellow and black enamel paint which are arranged compositionally to form a landscape of sorts with the high horizon line created by some of Rani’s remaining black paint skins.

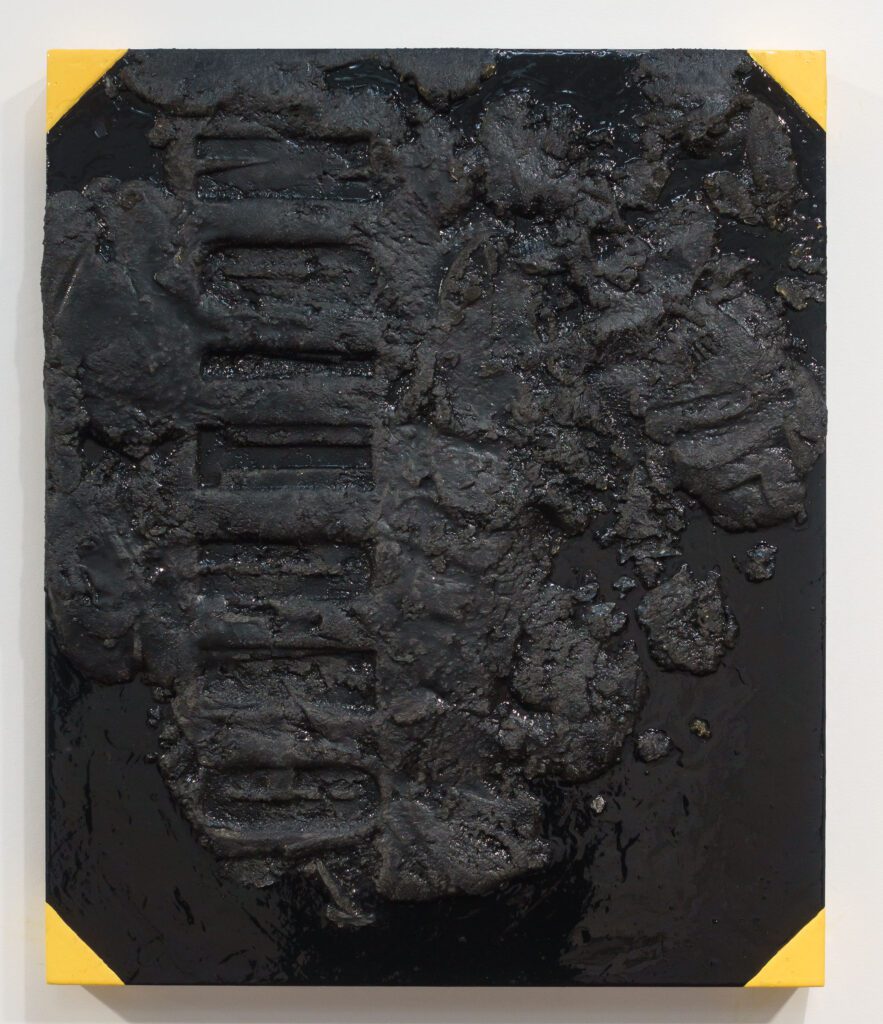

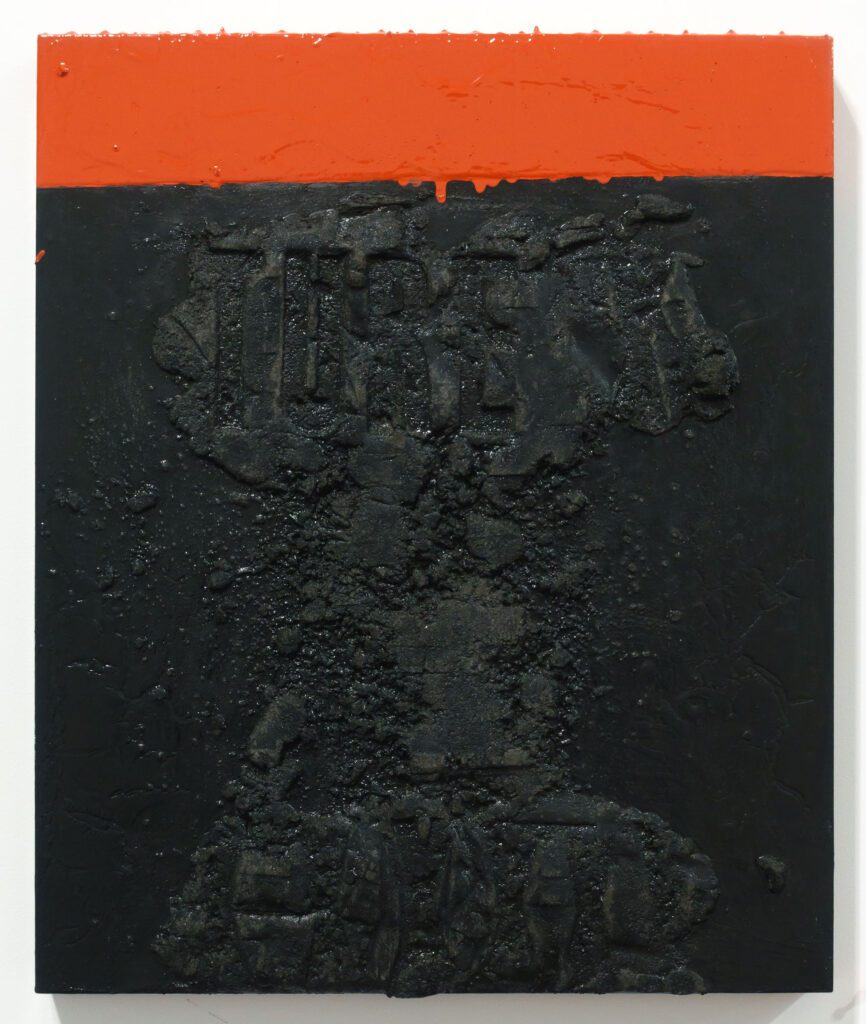

The artist casts what he describes as ‘sexy yet toxic’ industrial paint from these found or overlooked urban objects such as the sign here, tyre treads and barbeque plates. He also embeds screws and other hardware into the skeins and skins of his surfaces.

The geometric shapes that result in this particular composition –a narrow yellow rectangle and a larger black square seem at first a homage to modernism – Mondrian, Malevich, or locally, McCahon, but they also tell a story of colonialism and the missionaries’ outlawing of tattoo in the Cook Islands. When the London Missionary Society came to the Cook Islands, many cultural practices, including tattoo were banned under the ‘Blue Laws’. Blue law 10 (Ture X) concerned tattoo. If someone received a tattoo or gave one, they were punished by having to weed a square 12 yards by 12 yards.

The square in We Collide Together includes ground charcoal and black sand mixed with the paint to represent the pigments in the tattoo, the void in the landscape they created and the area weeded. Added to this are the words TURE X imprinted in stencilled capitals horizontally and CAUTION found vertically. There is a strong echo of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns in terms of the former’s Combines and the latter’s use of stencilling. While We Collide Together might appear conceptually cool, it’s a work imbued with emotion – of anger, heartbreak and respect for family and taonga.

Meanwhile, The Chaos of Hope, an all-over slickly black painting and perhaps the clearest landscape-based work, or is that seascape, gives its title to the exhibition.

If that mound of paint is Lion Rock, then the smoother third to the right is the Tasman sea. It’s Piha then. The mini-corrugations in the remaining two thirds speak of both Rani’s means of production – casting enamel paint from found industrial detritus, such as corrugated iron or the smaller corrugations of tin cans and also of the force of the surf as it repeatedly belted the black sand of the west coast and leaving juddered patterns behind.

The compositional ratio suggests the point of the view of the beach from the bank opposite the artist’s house on Garden Road. Despite the implied golden section, there was nothing harmonious about the Black Friday the cyclone hit.

There’s also a triangle cut out between the juncture of sand and sea that further speaks of this violence. The void is also suggestive of the heritage arts and the carving of Mangaia and the shark-tooth pattern that is universal across the Moana. It also connects this black seascape to the carved adze that sat sentinel-like at the entrance.

Black dominates in this exhibition along with white and the three primaries of red, yellow and blue. The black suggests the black night of the cyclone and the stygian black water that flooded Rani’s house and the surrounding township. Like everything in Rani’s practice, the colour symbolism is multi-layered.

The primaries suggest the colours of the paint factory and also of street signs, particularly of caution and stop. Red, yellow and white have taken on more symbolism since Cyclone Gabrielle. Red coloured stickers on damaged houses denote ENTRY PROHIBITED, yellow is RESTRICTED ACCESS and white – CAN BE USED. Sefton and Kirsten’s home was eventually ‘yellow stickered’ – meaning a no go. EQC have said it will be another six to seven months before anything even happens. Looters have added to the nihilism as did the leakiness of their initial temporary home. Things are understandably black then.

Similarly many of the titles are metaphoric – Clear My Throat, Whitewash or philosophical in outlook as in The Root of All Existence. In Knowledge Holders and Knowledge Holders #1, Sefton refers to the knowledge and skills his father Mii possessed in identifying hues and tones in the enamel paint in the factory, a skill passed down to Sefton when he worked in the factory after leaving school. He equates this with the traditional knowledge-holders of Mangaia, those who carved adzes and tattoo or passed down stories of origin or lineage.

The original Mangaian knowledge-holders are also implied in Hatch 3, or, rather the work speaks of their loss through the euphemistically described, blackbirding. This dark period of what is really only recent history saw Cook Islanders among those from other neighbouring Pacific nations taken as “migrant workers” by Peruvian ships. These traders were keen to make a profit by providing labour for Peru’s huge plantation-based export industry.

While slavery had been abolished in Peru in 1854, the government had passed a law in 1861 allowing the importation of (so-called) Chinese coolies and Polynesians. The following year, the first ship left for Peru from the northern Cooks, but a fleet of ships immediately returned to the Cook Islands as a whole. Documents record the events of recruitment which ranged from people leaving by choice, being misled and also those who were coerced on board or picked up from smaller fishing boats on the open sea and taken by force to Peru. All of those men taken from Mangaia were coerced on board and trapped there in the hold under the hatch.

They became the property of the Peruvians and were enslaved. Vast numbers of men, women and children died en route to Peru and even more died from disease and harsh working conditions on the plantations. Only something like 5% were ever repatriated and some to the wrong islands.[3] Such an exodus of people had a dire impact on the transmission of knowledge, culture and language, especially in the northern Cook Islands.

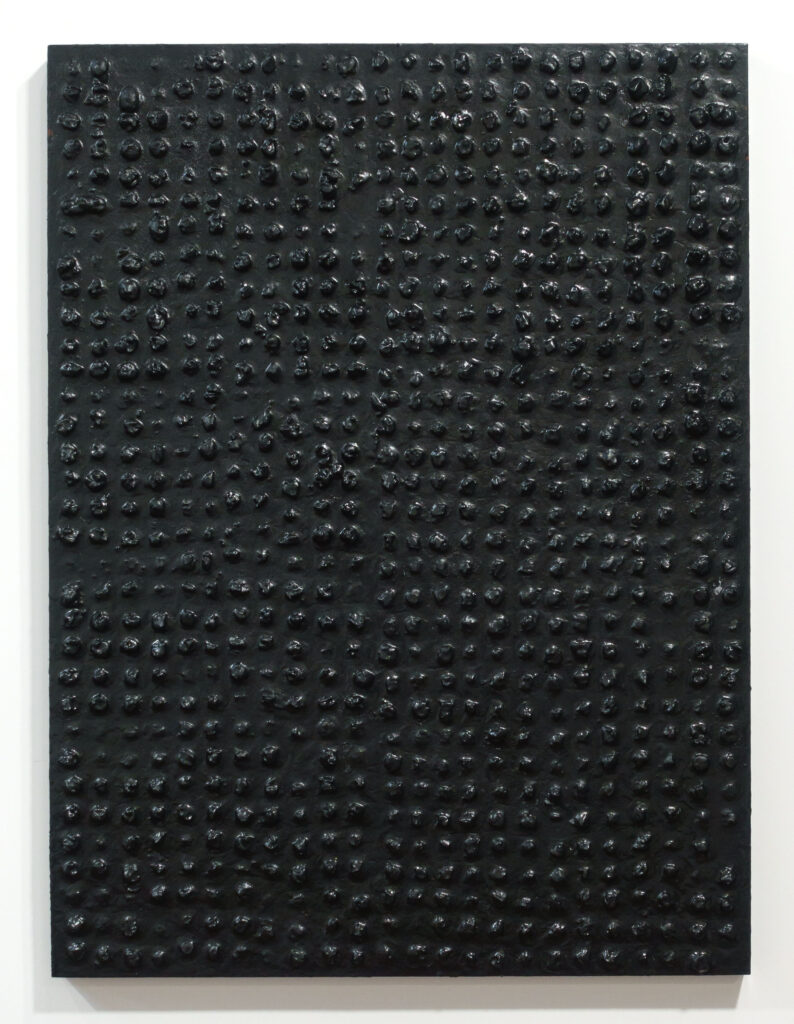

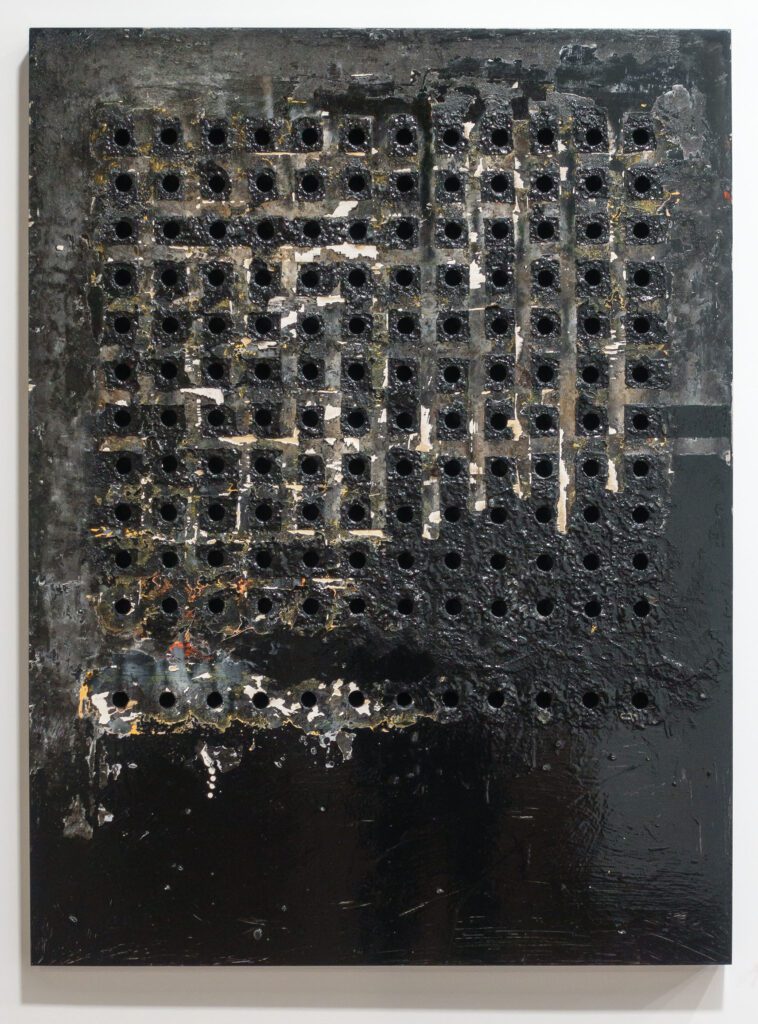

The title appears to be purely literal – a hatch is a hatch is a hatch to paraphrase Gertrude Stein, but the physical work communicates a palpable sense of loss. Hatch 3 is weighted with feeling, even when it was drying in the small bedroom of a suburban leaky home prior to exhibition.

Later, leading UK arts writer Charles Darwent visiting Tamaki Makaurau for the Auckland Writers’ Festival described it as a ‘complex, subtle work.’[4]

Rani suggests the hatch door of the slaver’s ship and emphasises this correlation by carving with a makeshift tool, in the spirit of Arte Povera, 144 square holes into the surface of Hatch 3. The holes are steeped in black paint which both suggests the darkness of the hold and the concomitant sense of captivity for those Cook Islanders who were blackbirded. The textured plasticity of Rani’s enamel paint further suggests the black pitch or ship’s glue used to waterproof the wooden deck and hull. Piha is there too in the form of black iron sand mixed with the paint.

Rani also draws a parallel between the square-punctured surface of Hatch 3 and the piercing of the turret-like shaft of his Mangaian adze which sat at the entrance of the exhibition. Those 144 holes are not there by coincidence either. They refer to the punishment meted out by missionaries to Mangaians for contravening Ture X (Blue Law 10) in relation to tattoo.

Writer Gertrude Stein had explained her oft-quoted line by saying that in the time of Homer, or of Chaucer, “the poet could use the name of the thing and the thing was really there.” [5] In Hatch 3, the ship’s hatch feels as if it is really there and its trompe-l’œil nature deepens this sense of actuality.

The ultimate thrust of Sefton Rani’s exhibition is made explicit by the title of The Sacred Labour of Our Fathers. It is a homage to Mii Rani making paint for a lifetime in the urban paint factories of Auckland, and, ultimately, to the father and son’s shared heritage to the Mangaian knowledge holders who carved Rani’s adze. Rani uses that same industrial paint to make contemporary Pacific art that is enriched through a thorough understanding of international practice and a deep reference to Cook Island history and ‘akapapa‘anga.[6]

Claire Chamberlain

Sefton Rani’s exhibition ‘[Crossroads]’ shows at PG Gallery 192 in Christchurch from September 12 to October 6.

- https://www.nzherald.co.nz/the-listener/new-zealand/listeners-top-100-list-new-zealands-most-intriguing-people/L3CKA67YRVAKBABME6KAMUDA5Y/

- https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/170168

- https://blog.tepapa.govt.nz/2017/08/04/cook-islands-language-week-language-culture-and-the-impact-of-slavers-in-paradise/

- https://twitter.com/darwent_charles/status/1660034886651252736?s=46&t=WKqfwPYjkP-XqHOKePg-kw

- https://isarosepress.com/about/our-story/

Sefton Rani is a full-time artist based in Auckland. Sefton describes himself as a maker whose material of choice is solidified paint skins. He calls finished works “industrial tapa” which are influenced by the marks and forms of traditional tapa, carving, tattoo, weaving and tivaevae. These works signify his Cook Islands heritage, and allow him to explore his “Pacificness”. This unusual material reflects time spent working in a paint factory and it allows him to investigate the materiality of paint as an object and the labour of immigrants as a substance with value.

Claire Chamberlain (Master of Arts Art History with Hons) currently teaches as part of the Art Today programme at Te Tuhi, one of New Zealand’s foremost contemporary art spaces. Prior to this, she was a secondary teacher of Art History for over 20 years. Claire has had an on-going role with New Zealand at the Venice Biennale as a patron herself since 2017, an invigilator for Lisa Reihana’s Emissaries in the same year and as Co-Chair of NZ at Venice Biennale Patrons.