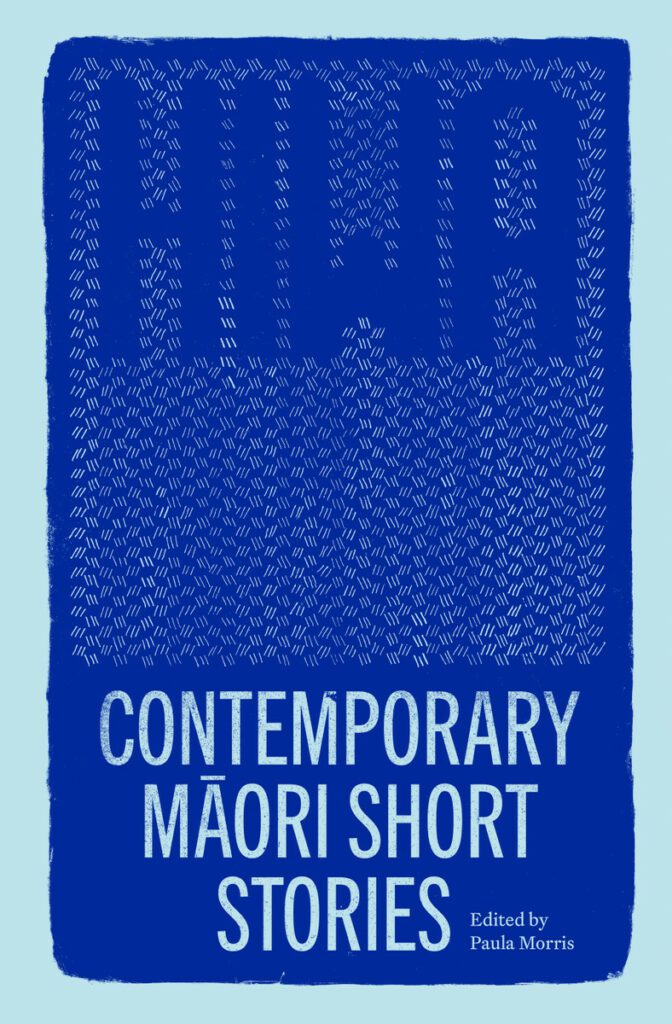

HIWA: Contemporary Māori Short Stories

HIWA: Contemporary Māori Short Stories edited by Paula Morris. AUP (2023). RRP: $45. PB, 271pp. ISBN: 978 86940 9951. Reviewed by Vaughan Rapatahana.

He aha te tikanga o tēnei kupu, Hiwa? I roto i tāna Tīmatanga Kōrero, ko te tohutoro a Paula Morris ‘Hiwa-i-te-rangi, te iwa me te whetū whakamutunga o te kāhui Matariki,’ me te whakauru i te whakamāramatanga a Rangi Matamua, ‘Ko te kupu ‘hiwa’ ko ‘te tūkaha o te tipu’.

Nā reira, ka whakatinana a Hiwa i te ingo kia tutuki ngā awhero me ngā wawata o te tangata, kia tupu i roto i te ao o te mārama, te ao o te whakatupu, me te tohu o tēnei paenga kōrero ‘tētahi wā anō o te tipu mō ngā kaituhi me ngā tuhituhinga Māori.’

Heoi anō, kare rawa a Morris i tino kōrero mō te take i whakahiatotia ai, i whakaputahia ai tēnei pukapuka; kārekau he take ariari mō tōna putanga i te tau 2023. Kārekau he punga taumaha a Hiwa, kāore he kaupapa tau kua whakaritea i tua atu i te whakaatu i ngā kōrero paki kanorau nā ētahi kaituhi Māori. Koia anō, he tokomaha ngā kaituhi ‘hou’ kāore i roto i ngā whārangi o tēnei paenga kōrero. Hei aha koa, he rawe te kite i ngā kohikohinga o pakiwaitara a ngā kaituhi Māori hei whakamaioha mā tātou katoa.

E 27 ngā paki poto i roto i tēnei pukapuka, he rerekē te roa mai i ngā tūtaki poto nā Jack Remiel Cottrell me te pōhauhau, tae atu ki te pūrākau tawhiti roa o Anthony Lapwood kimikimi me te whakawhitinga whakatipuranga. Nō kōna anō, ka kitea te tini o ngā momo kanorau i te wā e pānui ana i tēnei paenga kōrero, mai i ngā mahi nanakia kakati a ngā kēnga (“Charlie Horse” nā Alice Tawhai) tae noa ki te hua o te toihara ā iwi e rua – tino rāua ko huna – pēnei i roto i te kōrero kuku “Polypharmacy” nā J. Wiremu Kane.

He rerekē anō ngā takiwā wā me ngā wāhi o ngā paki, nā te mea karekau katoa e puta i roto o Aotearoa New Zealand o ināianei, i tuhia rānei e te tangata Māori i konei. Hei tauira ko “Paradise” nā Colleen Maria Lenihan ka tū ki Hapani, ko “The Kiss” nā Patricia Grace kei Itari, ko ngā kaituhi pēnei i a David Geary, Aramiha Harwood, me Nick Twemlow, e noho ana ki tāwāhi. E whakaturuma ana tēnei i te mea kāore ngā kaituhi Māori e herea e ngā rohe matawhenua e tūmanakohia ana, engari e wātea ana ki te tuhi ahatanga he aha, ahatanga ki hea.

Pērā me ētahi kohikohinga, he pai ake te mahi o ētahi o ngā kōrero paki i ētahi atu, ahakoa te āhua o te kaupapa, te āhua o te tāera. Nō konā, ka tū ētahi. Hei tauira, te kōrero paki pūkare a.k.a nā Aramiha Harwood, te tino whakaahuatanga a Kelly Ana Morey mō te oati a Maungapōhatu rāua ko Rua Kenana, me te tūtaki a tētahi kotiro ki e rua—ko “Faithful and True”—e hanga ana mō te pānuitanga kaha, he pērā anō a “Pai”, nā Rawinia Parata, he whakaahua whai kiko e ahu mai ana i ngā rangirua o te oranga o he matua wahine Māori takitahi. Ka mihi anō ahau ki ētahi atu pēnei i a K.T. Harrison (“Colours”) me Shelley Burne-Field (“The Bargain and the Putōrino”) me Kōtuku Titihuia Nuttall (“Moko”) nā te mea e whakamātau ana rātou ki te whakamārama i ngā matea uaua—a tētahi wā—o te noho Māori, me/rānei. o te whakamātau (anō) ki te kite i taua mātau ā-wheako. I taua wā, ko te putanga whakahou a Araina Ngarewa o “Ngā Toa Pātea” e tika ana kia tino whakahuahia, nā te mea he rite pukuhohe ki te kiriata a Billy T. James.

Tekau mā rima o ngā paki kua whakaputahia ki ētahi atu wāhi, ko ētahi mai i te tau 2006. A, ki te kī tātou i ngā kōrero ‘hou’ hei rite ki te ‘ināianei’ ka whakaaro tēnei he āhua o te

t o r o n g a, nā ngā kaipānui taiohi, e.

E wha anake kua tuhia ki te reo Māori. He tohu pōuri tēnei mō te kōrero a Morris-i tana whakakōwaro i tētahi kaupapa nui mai i te rokiroki kawainga o Te Ao Mārama i te tau 1992-ngā kupu akoako me ngā kōrero e pēnei ana ‘kei te haere tonu te nōnoki mō te pukapuka reorua’. Ko te pōuri, nō te mea ki ahau nei, ko te whakapuaki i a koe anō i roto i tona ake reo ka uruhia atu ki roto i ngā āria me ngā māharahara kāore i te rite ki tētahi atu reo, i tohuia e ngā kōrero poto i tuhia i te reo Māori kei konei. Te mea ai, ko te kōrero a Tā James Henry i mua ‘Ko te reo te mauri o te mana Māori’.

Hei whakamutunga, he rawe te kite i tēnei paenga kōrero kua taia. He rawe hoki ki te kite i ētahi atu paenga kōrero hōu o ngā tuhituhinga Māori kua taia, pēnei Te Awa o Kupu raūa ko Ngā Kupu Wero, he mea whakamere, he maha anō ngā kaituhi i roto i a Hiwa.

Ko ēnei taitara kāore i te whakataetae, engari ka whakaotinga tētahi ki tētahi; ko te maha o ngā paenga kōrero pēnei ka pai ake, i te mea ko te tīkanga, ka whakarite mātau he ‘tuhi pai’ o rātau wāhanga. Ko Hiwa me ērā atu taitara he whakanui i te tere o te tipu me te rere o te awa o ngā tuhinga auaha me ngā kōrero pono a te Māori.

Vaughan Rapatahana (Te Ātiawa)

[‘Translation’

What is the meaning of this word, Hiwa? In her Introduction, Paula Morris refers to ‘Hiwa-i-te-rangi, the ninth and final star of the Matariki cluster,’ and includes Rangi Matamua’s definition, ‘The word ‘hiwa’ means ‘vigorous of growth.’

As such, Hiwa epitomises the desire for one’s ambitions and aspirations to be fulfilled, to prosper into the world of light, the world of advancement, and as such this anthology represents ‘yet another time of growth for Māori writers and writing.’

Morris never does state exactly why this anthology was collated and published; there is no obvious rationale for its appearance during 2023. Hiwa seems to have no weighty anchor, no set agenda other than to present a diverse array of short stories by Māori authors. However, it is great to see collections of fiction by Māori authors for us all to appreciate.

There are 27 stories in this volume, varying in length from Jack Remiel Cottrell’s brief encounters with absurdity, through to Anthony Lapwood’s far longer fantastical and transgenerational romance. As such, there is a marked continuum of genre diversity when reading through the anthology, from intense gang brutality (Alice Tawhai’s “Charlie Horse”) through to the depiction of both outright and latent racial discrimination, such as in J. Wiremu Kane’s haunting “Polypharmacy.”

The settings of the stories vary markedly, for by no means are all set within contemporary Aotearoa New Zealand, nor written by Māori resident here. For example, “Paradise” by Colleen Maria Lenihan takes place in Japan and “The Kiss” by Patricia Grace takes place in Italy, while writers such as David Geary, Aramiha Harwood, and Nick Twemlow all reside overseas. This affirms the fact that Māori writers are not restricted by expected geographical boundaries, but are free to write whatever, wherever.

As with any collection, some of the stories work better than others, regardless of their thematic or stylistic character. Accordingly, some stand out. For example, Aramiha Harwood’s evocative story “a.k.a,” and Kelly Ana Morey’s excellent depiction of the promise of Maungapōhatu and Rua Kenana and a young girl’s encounter with both—titled “Faithful and True”—make for compulsive reading, as does “Pai,” by Rawinia Parata, a based-on-life portrayal of the uncertainties of being a solo matua wahine Māori. I also admire others such as those by K.T. Harrison (“Colours”) and Shelley Burne-Field (“The Bargain and the Putōrino”) and Kōtuku Titihuia Nuttall (“Moko”) precisely because they do strive to explicate the sometime arduous exigencies of being Māori, and/or of trying to (re)discover such experientiality. Meanwhile, Araina Ngarewa’s updated version of “Pātea Warriors” is also well worthy of mention, because it is as funny as a Billy T. James skit.

Fifteen of the stories have been published elsewhere, some as far back as 2006. If we are to take ‘contemporary’ as equivalent to ‘now’ this might be considered rather a stretch by younger readers.

Four only are written in te reo Māori, which is sadly indicative of what Morris—in echoing a key point from the harbinger collective of Te Ao Mārama in 1992—notes and quotes as the ‘struggle for a bilingual literature continues.’ Sad, because for me, expressing onself in one’s own language necessarily involves including concepts and concerns that another tongue does not often have an equivalent for, as so well evidenced by the short stories included here penned in te reo Māori. After all, as Sir James Henare used to say ‘Ko te reo te mauri o te mana Māori.’ (The language is the life essence of Māori existence).

To conclude, it is great to see this anthology published, as it is to see other recent anthologies of writing by Māori, such as Te Awa o Kupu and Ngā Kupu Wero, which interestingly, share several writers as represented in Hiwa. Such titles do not compete, rather they complement each other; in fact the more such anthologies the merrier, given that, of course, we ensure their contents are ‘well-written.’ Hiwa and these other titles are a celebration of the rapidly growing and flowing river of both creative and non-fiction writing by Māori.]

A longer version of this review appeared in Landfall Reviews Online.

Ngā mihi maioha to Dr Georgina Stewart, who so generously shared their te reo Māori expertise and offered guidance to takahē on this review.

Vaughan Rapatahana commutes between Hong Kong SAR, Philippines and Aotearoa New Zealand. He is widely published across several genres in Māori and English and his work has been translated into Bahasa Malaysia, Italian, French, Mandarin. He participated in World Poetry Recital Night, Kuala Lumpur, September 2019, and Poetry International, the Southbank Centre, London in October 2019—in the launch of Poems from the Edge of Extinction and in Incendiary Art: the power of disruptive poetry. Vaughan’s poem ‘tahi kupu anake’ is included in the presentation by Tove Skutnabb-Kangas to United Nations Forum on Minority Issues in Geneva in November 2019.