Hine Toa

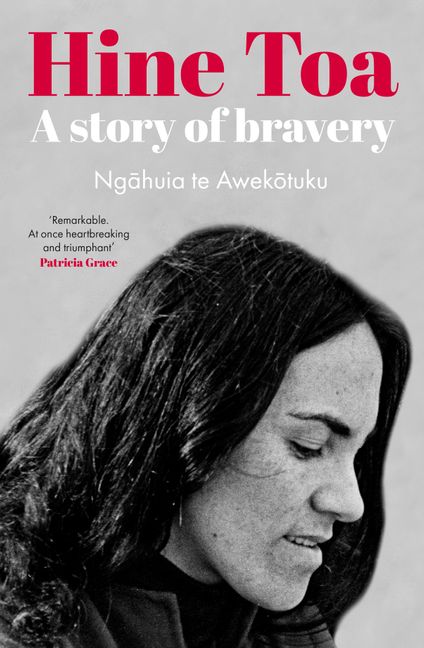

Hine Toa by Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku. HarperCollins (2024). RRP: $39.99. PB, 336pp. ISBN: 9781775542322. Reviewed by Isla Huia.

Hine Toa is the blazing memoir from activist, rangatira, and advocate for the underdog, Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku. Te Awekōtuku’s early days at the pā of Ōhinemotu, her conflicted rangatahitanga as a student and wāhine takatāpui, and her young adulthood in Tāmaki Makaurau amidst growing tensions and the birth of movements like Ngā Tamatoa are all recounted in this story of her life—of joy, tension, and finding her place among it all. Throughout the timeline of this book, through the many changes and adaptations within Te Awekōtuku herself and the worlds and communities she exists within, one thing is consistent: her experience of being ‘different,’ of being on the outside of everybody else’s club, and in turn, her ever-growing commitment to fighting for the rights of the oppressed, of the minority, and of the cast-out.

‘Once upon a time there was a pet tuatara named Kiriwhetū; her reptile skin was marked with stars. She had looked after a leading Maketū family for over a hundred years and was already like an ancient ghost when my kuia was a young girl, not quite a woman. My kuia was there when it happened, she told us this story.’

There’s no doubt that Te Awekōtuku’s spirit of advocating for those facing barriers was a trait passed onto her from a long whakapapa of hine toa—from both her biological whānau, and those chosen for her and by her. It is evident that her culture, viewed through the lens of the pā, her aunties, and her kaumātua, was a defining factor in shaping the woman she became. In saying that, what makes this story stand out from other Māori memoirs, is Te Awekōtuku’s ability to recall authentically the complications and conflicts that being Māori in Rotorua in the 1950s provided.

Rather than seeing her Māoritanga through rose-tinted lenses, the author sees it through the lens of friction: her ‘Pākehā voice’ but her ‘Māori blood,’ her Catholicism but also her pūrākau, the incompatibility of her body revered as a metre maid but patronised regarding its lack of academic potential. To work with her kuia on the harakeke, to bathe with her cousins, to be expected of being capable of so little, to be desperate to run away and yet also run home—Hine Toa relays a life of trying to find a home amongst her people, her whāngaitanga, her flatmates, and ultimately herself, as she comes to understand what being Māori means to her—which tikanga serve her well, which bits of her are colonised, which keeps her in line with those who came first, and which parts set her free.

‘They all rose to join him. Their fierce vitality stunned me. The visitors and their talking chiefs responded accordingly. Outside, darkness fell as I sat there, watching, listening, recording it all in my head. But… had I come home, really?’

Much like Te Awekōtuku’s conflict between her Māoritanga and the ever-developing Western world, her undoubtable queerness was another facet of her character that proved itself to be the cause of friction in her life. Detailing her younger years, and the adolescent experiences that led her to both more strife and more comfort, the author tells a tale familiar to many in our LGBTQIA+ community; one of longing, searching, finding, and relinquishing. Although she was raised around a whānau that included those who lived non-heterosexual livelihoods, she was also aware even then that these lives went unlabelled, unspoken, and ultimately hidden. It wasn’t until she found herself in Tāmaki Makaurau that she began to live in a way that she couldn’t at home, to befriend others in her community, and to love without the veil of secrecy she had for so long adopted. Throughout the memoir, the author’s plight to live freely as a wahine Māori and openly as a wahine takatāpui are intrinsically intertwined. In fighting for one, she often finds herself pausing in her fight for the other. Of the many wero laid down before her, Te Awekōtuku relays the trials and the joy that come from being different, finding your people, and ultimately, yourself.

‘I’m not sure when the feeling began—a burn in my puku, a tight, warm knowing.’

Particularly in the latter half of Hine Toa, it feels that this notion of finding oneself is ultimately solidified in the mahi and activism that Te Awekōtuku finds herself heavily involved in; it is her way of helping others to find themselves as well, and of helping society to celebrate people as their authentic selves. In Tāmaki Makaurau, she rose in her power as a founding member of Ngā Tamatoa and the Women’s and Gay Liberation movements, alongside others whose names are synonymous with resistance, art, and demonstration. Talking poetry with Hone Tūwhare in a Grafton villa, sitting in protest meetings with Syd and Hana Jackson, listening to Hone Ngata at the Hamilton Teachers College, writing scripts with Sue Kedgley, riding in the car with Tame Iti, interviewing Germaine Greer, working with her cousin Merata Mita; these were places that she flourished, politically and personally, and the people in whom it seems she found her feet.

Te Awekōtuku distributed pamphlets against America’s involvement in the Vietnam war, stamped the streets against apartheid and the Springbok Tour, held placards at Waitangi, staged a performance in Albert Park on Suffrage Day, protected her marae from the ruinous busses of tourists, drank with the Kamp Girls, rode the bus with the Polynesian Panthers, was reassured by the manaakitanga of Tini ‘Whetū’ Marama Tirikātene-Sullivan, and spent a night in the cells for attempting to paint ‘Return Our Patus Now’ on the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Many, like myself, will know these names and have heard bites of these stories, but from the mouth of Te Awekōtuku herself, the power and creativity of these efforts can be truly realised and appreciated. These are the tales of exactly the type of tūpuna I want to be.

‘That day at Te Tokanga Nui a Noho, as children of the Revolution, we knew our place. We were there to help.’

All in all, Hine Toa is an example of the innate importance of storytelling within te ao Māori, and our culture as a whole. Like our sacred narratives and ancient pūrākau, the sharing of story across generations is an avenue by which we value the lives and experiences of those around us, and refuse to let that knowledge be lost. In writing this memoir, Te Awekōtuku has done just that; providing an insight into our people and a transformative period of time in our nation’s history, putting the spotlight on biculturalism, sexuality, and activism as key kaupapa. It’s a reminder not to take for granted the mātauranga that has been gathered to create a better, different society for us today; and to reflect on those fights that have been fought both before us, and for us.

Isla Huia (Te Āti Haunui a-Pāpārangi, Uenuku) is a te reo Māori teacher and kaituhi from Ōtautahi. Her work has been published in journals such as Catalyst, takahē, PŪHIA and Awa Wāhine, and she has performed at numerous events, competitions and festivals around Aotearoa. Her debut collection of poetry, Talia, was released in May 2023 by Dead Bird Books, and was shortlisted for the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards 2024.