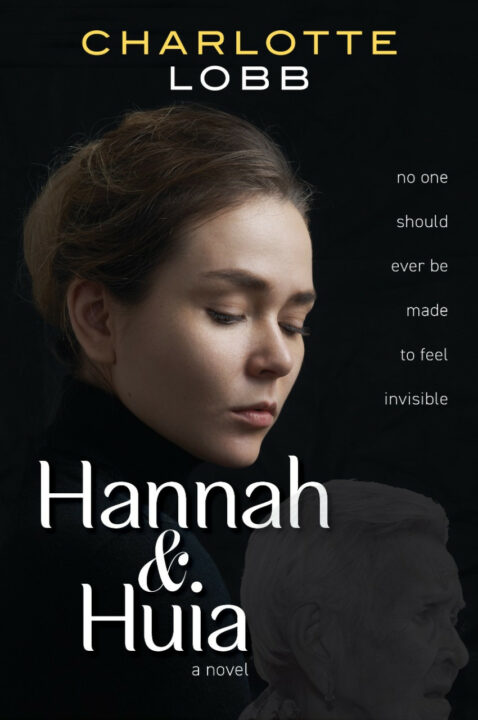

Hannah & Huia

Hannah and Huia by Charlotte Lobb. Quentin Wilson Publishing (2023). RRP: $37.50. PB, 240pp. ISBN: 9781991103109. Reviewed by Rebecca Styles.

In the author’s note to Charlotte Lobb’s debut novel, she explains her own challenges with the ‘discomfort of owning and accepting my own battles with depression, anxiety, PTSD and worse’ (p.238). While the novel is entirely fiction, one of her aims in writing it is to allow ‘readers to experience the complexities of mental illness,’ as well as examining her own feelings of shame and stigma around mental illness (p.238).

Hannah has been admitted to a mental health unit after taking an overdose. While there, she becomes fixated on a fellow patient, Huia, an older Māori woman who utters seemingly random three-word sentences. One particular chain of words—’Sun, rain, bye-bye,’ (p.30)—resonates with Hannah. She doesn’t think they are random and sets out to work out what Huia means.

The story is told in three parts: the first from Hannah, the second from Huia and then back to Hannah for the final section. While we start in the contemporary world, Huia’s section takes us back to the late 1960s to a home for unwed mothers. Think Magdalene Girls, but in Lobb’s novel there’s no obvious Church involvement, though religion is present. Huia and her counterparts work in the laundry, and do other chores, while their babies grow inside them.

Although Lobb has experienced mental health units, in many ways, I found Huia’s story more absorbing. It brings the story of unwed mothers to the fore, and we get to know the other young women who are in the same predicament. Sometimes there is a bit too much telling—typically, at the end or the beginning of chapters where it’s obvious the character is looking back and making comment, e.g. ‘Now that’s all nothing more than a distant memory,’ (p.144). For me, staying in the scene and leaving the reader to come to that conclusion would be more satisfying.

At a pivotal moment in Huia’s story there’s an odd reference to what other events happened on the same date. ‘For some this will always be known as the date of the UK release of the Beatles’ hit songs “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane”. Others will […] report that the likes of Kelly Carlson, Paris Hilton […] share this as their birth date,’ (p 140). It’s just unnecessary and jolts us out of the historical narrative and the person we’re really interested in—Huia.

While the atmosphere of the mental health unit in Hannah’s story felt compelling—the busyness and the interactions she has with the other patients and staff—my main bugbear was with how her mental health experience is written. Hannah has regular appointments with her doctor where she remains silent. Yet, she articulates, quite clearly, her loss in her own mind (and therefore to the readers). This silence, the inability to voice pain, is likely true to the experience of post-traumatic stress, yet in the novel it feels like a literary device to halt in order to keep the story going. Her recovery is being held back to draw out the story, to keep her in the ward so she can work out what Huia is saying. She also has recurring nightmares which, after the first two, are repetitive. Again, while they may be true to her experience of mental health, it also felt like a literary device, and a bit contrived.

Writing about mental illness is incredibly difficult, especially from the first-person point of view. How can you make a compelling and cohesive narrative from the voice of a person whose own narrative is unravelling? The conventions of storytelling and the experience of mental illness are not easy to marry. Lobb’s novel is a valiant effort.

Rebecca Styles (PhD in creative writing at Massey University) has written a novel based on an ancestor’s experience of mental illness at Seacliff Asylum. She’s had short stories published in New Zealand journals and anthologies, and taught short story writing at Wellington High School Community Education Centre for ten years.