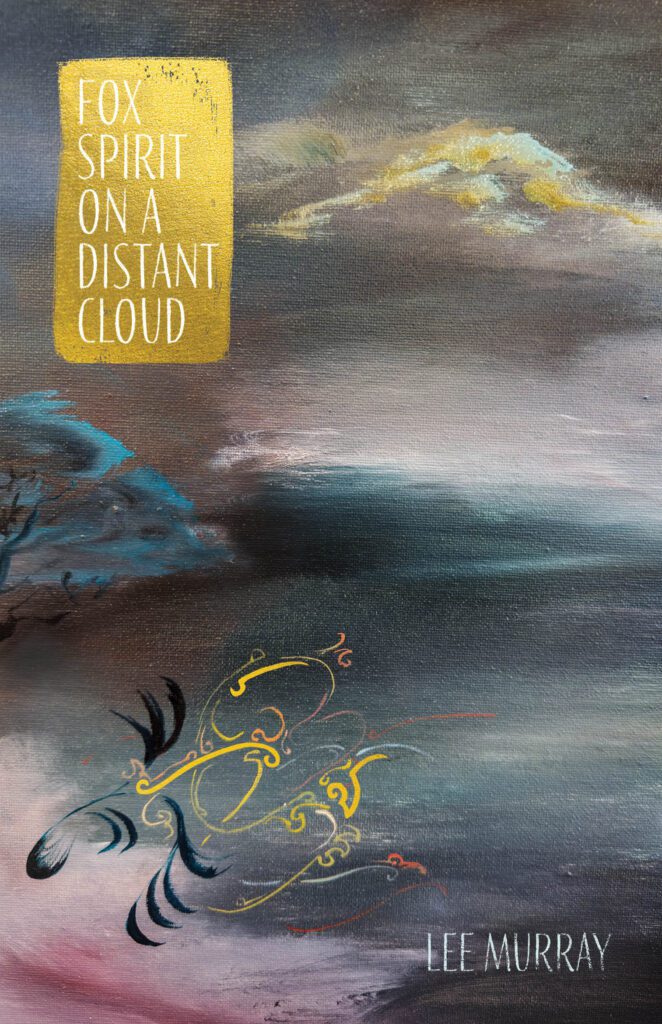

Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud

Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud by Lee Murray. The Cuba Press (2024). RRP: $28. PB, 138pp. ISBN: 9781988595771. Reviewed by Nurus Van Vliet.

What a thrill and an honour it was to read this book. Author Lee Murray’s novel-in-verse, Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud, is evocative from cover to cover and reading it proved a visceral experience, an instinctual response to the immensity of its scope. The imagined true lives of Chinese girls and women who migrated to various parts of Aotearoa are relived in these immersive and transporting stories that stretch over nearly a century.

The fox spirit, or húli jīng 狐狸精, of Chinese lore is a supernatural creature that resists easy definition. A spirit, a demon, a shapeshifter, it straddles the uncanny space between mortal and immortal realms. Neither malevolent nor benevolent, the húli jīng is the epitome of pure being, quickly adapting to its surroundings in order to best live. Although genderless, more often than not it is depicted as an exceedingly alluring woman, who is simultaneously capable of striking both arousal and fear in the hearts of men.

It is said that the fox spirit tries on a series of skulls over its lifetime, inhabiting different lifetimes in turn, in order to transcend earthly constraints towards blissful spiritual ascension.

It is said that it is most powerful when in its nine-tailed form.

No choice could have been better than this summoning of the enduring fox spirit as the all-encompassing narrator for the numerous unquiet spirits of nameless and faceless girls and women inhabiting these pages.

One skull for one life, one life for one tail, nine tails for nine tales; the collection steadily arcs across this scaffold, allowing disparate fragments to be loosely threaded into a cohesive whole. Gathered together, their individual stories traverse broad swathes of history recording life and strife as experienced by Chinese-New Zealander communities who once voyaged here, their stories stretching from pioneering New Gold Mountain days to more recent times. Their unique experiences inform a larger tapestry of those affecting a growing Chinese and Asian diaspora, sharing a multitude of reasons for their migration.

Murray wrote Fox Spirit during the Covid-19 pandemic, a time of heightened violent anti-Asian racism which influenced her text, but also, this is a repository that delicately holds the weighted resonance of centuries. Like the unassuming might of the fox spirit, the masterfully sustained ‘you’ of the second person point-of-view is a steady anchor, balancing the vast scope that such an expansive, all-encompassing work demands.

Between discriminatory NZ government policies of the time such as the Chinese Poll Tax (£10, later increased to £100) and limits on the number of Chinese immigrants into the country (one passenger for every 10 tons of cargo, later increased to 200 tons, per ship), it would have been a tough journey to even reach Aotearoa’s shores. Forced to bear the brunt of Yellow Peril and assimilationist measures, it would have been no easier on arrival. For Chinese women, these hurdles and dangers would have intensified, that is if they were even considered worth the exorbitant cost of entry to begin with. Not only were they isolated in this new and changing world, language barriers separated them from the potential solace of kinship and community, and the cultural space their own language offered worked against them.

As if it were not enough to be at the mercy of hungry Western ghosts, an apparent vessel for prejudiced stereotypes, misogyny also came from within. Racial and male violence both. Nameless and faceless, they are stripped to generic identities that hold more worth than the fullness of their truthful selves; girl, woman, daughter, wife, mother. Like the radical 女, a ‘good’ Chinese woman is designed to kneel, heads willowed, subservient to men, dreams surrendered in sacrifice. She is to keep her individual woes silent so as to not lose collective face. She can just as easily be made monstrous, the same radical 女 implicated in characters deemed unsavoury—envious, traitorous, bewitching—not unlike the wily duality of a fox spirit. Despite the horrors they endured, it was perhaps most painful to read how the perceived shame of not being enough, as encoded in written language, is translated into the body—a hollowing out, room for a fox’s tail to try to hide.

As a being that exists both physically and metaphysically, the fox spirit undergoes its own journey of ascension alongside these girls and women. Its foreign impossibility in this space means danger is a tangible possibility at all times, outside of the danger befalling the borrowed female lives.

In their new landscape, the fox spirit is a quiet un-silencing, a room to breathe, a place of power folded into one’s self.

In this new Aotearoa landscape, from vast country to urban city, the fox spirit has to negotiate its own belonging with the spirits of those who roam the land. The language used reflects this overarching journey, becoming steadily more fluent in place names and landmarks and specific dangers that lurk.

Notably, artistry of language is a strength here, the text buoyantly articulating a Chinese-Aotearoa worldview (Murray is of Chinese-Pākehā heritage). At a sentence level, these works of lyrical prose poetry are at once a delight and a method of honouring the spirit of the book. A visible home is built into the words of an adopted language, a bridge connecting past and present, strengthening the foundations of a future.

The fox spirit may be trying on skulls for size, but so too are the writer and her audience, inhabiting its guise.

Writing from this helm ensures a steadfast viewpoint rooted in one’s heritage, honouring both the archived and unrecorded lives that came before.

To write from this view retains the sensation that one can adapt as many times as is possible, yet still feel queer and otherworldly. An anomaly, as contextualised by Geneve Flynn, in her excellent introduction to the book, positioning this work in the time old literary tradition of Chinese zhiguai: ‘The stories in this collection are more than poetry, more than fictions; they are zhiguai. They are accounts of anomalies: not so much supernatural entities but Chinese women uprooted and replanted on foreign soil.’

To write through the eyes of the fox spirit risks discordant singularity in what is a defiant, eloquent chorus of voices singing across space and time. The grounding ‘you’ comes to the rescue. What has it all been for?

Fox spirit, writer, and reader all come to their own dawn. The sun rises on an understanding that these lives have not set for naught. These lives have not been gratuitously excavated, instead they have been witnessed and brought to light. In raising their voices, the storyteller breathes life into dust, so their stories may continue to echo across generations, remaining alive in our collective remembrance. As Murray notes, ‘we owe these pioneer women a deep and abiding gratitude.’

In homage to those who have come before and forged new ways of being, we walk backwards into our collective future. Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud is a testament to art as alchemy, a positive force introduced into the world. It seamlessly slots into cultural literary traditions of zhiguai, while also positioning itself within the genealogies of growing local Chinese-New Zealander writing, literature speaking to the experiences of Asian women in the (Western) diaspora, as well as a local literary canon hungry for more multi-heritage voices. This remarkable taonga is surely destined to be an Aotearoa classic.

Nurus Van Vliet is an avid reader and bibliophile. She posts about the books she’s been reading on Instagram @ns510reads.