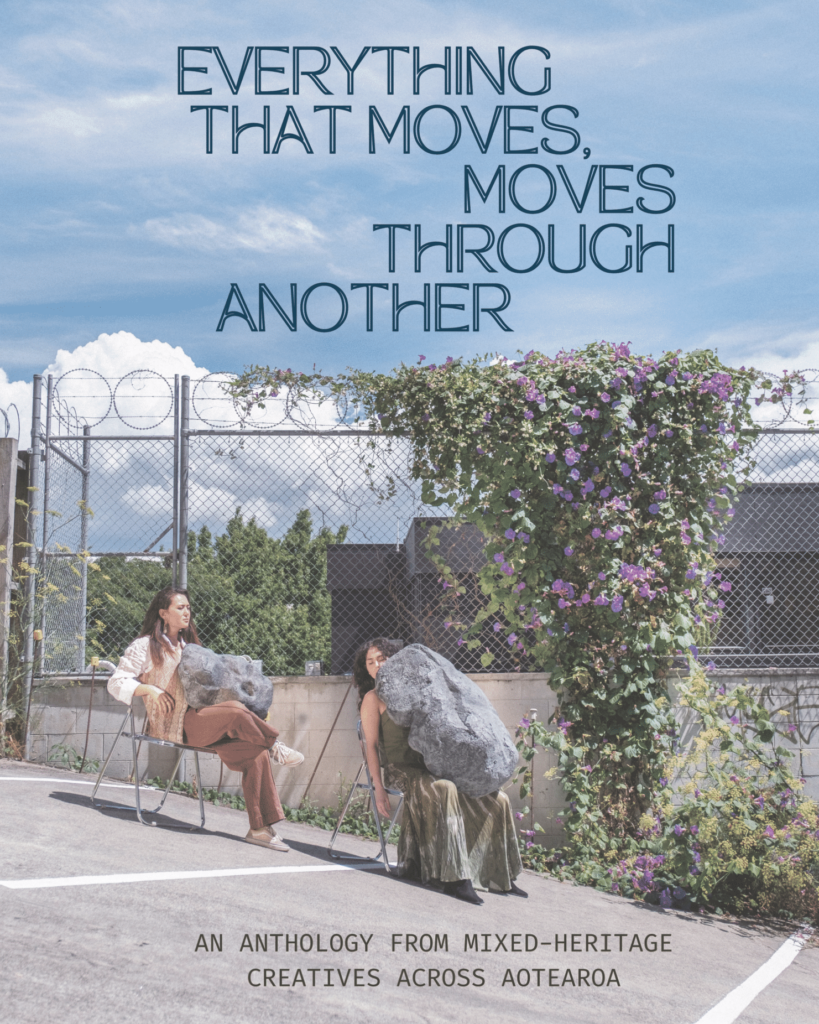

Everything That Moves, Moves Through Another

Everything That Moves, Moves Through Another edited by Jennifer Cheuk. 5ever Books (2024). RRP: $65. PB, 231pp. ISBN: 9780473713560. Reviewed by Vera Hua Dong.

Everything That Moves, Moves Through Another is a lavish tapestry of sounds and shapes of languages, colours and aromas of spices, and most of all, of the lightness and heaviness of being mixed-heritage. This mixed-genre, mixed-medium collection is at different times bitter and sweet, reflective and witty, but all deadly honest and intensely personal. It gives authentic voices a rare opportunity to tell their own stories.

As a new immigrant from mainland China, I often ask myself, where and what is my home? Is it where Mandarin is spoken? Is it where I grew up and where my parents still live? Is it the farm in Far North New Zealand where my mixed-heritage children grew up and where my English husband calls home?

In Cadence Chung’s “Visitation (the painted Chinagirl),” the first of a suite of poems titled “Visitation,” the speaker laments, ‘The moon shines through the window like a Li Bai poem. Are you missing home? I could have asked. The only thing I could ask her—something unanswerable for us both.’ When you are a 4th generation Chinese New Zealander, the home where your great-great-grandparents left is probably too far to reach, too vague to imagine, and too distant to understand. However, the mother tongue, the classic poetry, is there, calling for attention and waiting to be explored and spoken. ‘I think of how my mouth clogs when I speak Cantonese, all the apologies that never make up for my traitorous tongue that knows only of Eliot and Joyce.’ I remember sharing my sense of guilt for failing to teach my son Mandarin with an old schoolmate of mine. She said, with a straight face and tone, that my ancestors would be in such a rage that they could crawl out of their tombs to haunt me.

“What makes up me,” a sequence of poems by Daisy Remington, is a personal declaration that who she is is entirely her own making. She comes to the realisation: ‘Nature loves diversity, its strengths / So maybe the fact that I am mixed is just a glimpse / Into the true collectiveness of that; that exists’ (“Exploration”). In “Possibility,” her resolution is final: ‘I get to pick the parts I like most / And that will be what makes up me.’

I learned from Nkhaya Paulsen-More’s “Walking between two worlds” glossary that ‘huì’ (会) means a meeting, the same in te reo Māori and Chinese, with slightly different pronunciation and tone. However, ‘hua’ means the opposite. In te reo Māori, it means ‘I’ll cut your head off and boil it and eat it.’ In Chinese, huá (华) means ‘blossom,’ ‘prosperity,’ and ‘glamour,’ and the character represents the Chinese ethnicity. Huá (华) is my given name gifted to me by my grandparents. My son’s middle name in Chinese and Welsh is Kai (恺), which has the same meaning in both languages—peaceful joy. This is another curious but possibly untraceable coincidence. Discovering such unexplainable similarities and differences in different languages is rather mysterious and exciting. You wonder how languages evolve through human migration, ocean voyages, spice trade, and colonisation.

The installation piece “Black Tree Bridge” by Chye-Ling Huang is a collaboration project, a journey of reconciliation of her ‘Chineseness, duality and identity itself.’ It reminds me of the legendary Taiwanese film director Hou Hsian-hsien’s semi-autobiographical film The time to live and the time to die. In it, his grandma is confused about where she now lives—a village in Jia Yi, a town in the South of Taiwan. Every morning, she attempts to cross the bridge at the village entrance to go back to her home in Guangdong province. Nobody ever has a heart to break her illusion.

We cannot contemplate cultures without talking about kai—its imprint on us is inescapable, no matter who we are or where we are from. “What are you?” by Jill and Lindsay de Roos, and “Kechil-Kechil chili padi: Ahakoa he iti, he kaha nga hirikaka” by Dr Meri Haami and Dr Carole Fernandez take on different journeys but for the same goal: ‘rebinding cultural embeddedness together through our whānau stories of kai,’ one through Southeast Asian kai, one through South African spices influenced by cuisines from all around the world.

Everything That Moves, Moves Through Another is a fabulous treat offering many different tastes and flavours: comics of growing up as a singled-out alien, cross-ethnicity cross-gender family stories, folklore-inspired magic-realism fiction, photography, personal memoirs, a play/comic and many more. The diversity of genres and forms is the anthology’s point: embrace diversity; that’s where the beauty, creativity and energy lie and where the enjoyment and deep reflection come from.

What is the best thing about this collection? It’s the fact it is here, that it has been published. As Yani Widjaja said in “Oey 黄 is for Widjaja”: ‘Here, in New Zealand, I can feel and live the nuances of being Chinese-Indonesian. I can decide how I want to explore my mixed ethnicity, my Chinese heritage, and express myself in ways that might otherwise feel inhibited in Indonesia. This is my great privilege as the latest descendant in a long line of sojourners, merchants and migrants.’

This is a rich and heavy book to behold with an attitude of openness that we must continue to grow.

Writing flash fiction helps Vera Hua Dong reconnect with her childhood, family, and old friends. Her stories and poetry have been published at Flash Frontier and Reflex Fiction, and collected by New Zealand anthologies. She won the National Flash Fiction Day competition in 2022, and won the Northland regional prize in 2020, 2021 and 2022. Vera was born and grew up in Nantong, a small city along the east coast of China. She is now living in Kerikeri, New Zealand.