Dreampunk: The Art of Maryrose Crook

Although an exceptional painter, Maryrose Crook might be better known to some as a musician. She and her husband Brian make up the psychedelic folk-noir alt-country band The Renderers. Formed in Christchurch in 1989 borrowing members from The 3Ds, Pumice, The Verlaines, The Dead C and King Loser, trying to pin the bands musical style down to a mainstream genre is a fool’s errand. With releases through Flying Nun in New Zealand, and with Merge, Stiltbreeze, and Drag City in the United States, they toured Aotearoa as the backing band for Bonnie Prince Billy in 1997 to great reviews.

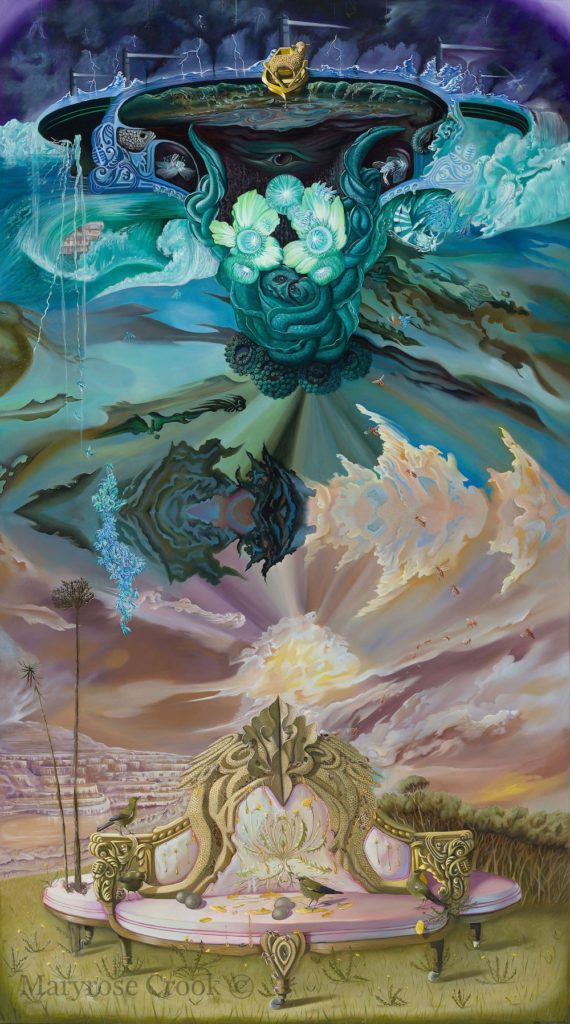

But Crook’s painting is no less interesting or accomplished. She is self-taught and began exhibiting her first paintings in Dunedin cafés in 1995, having moved to Port Chalmers two years previously. Precociously, the Dunedin Public Art Gallery invited her to exhibit within a year. It’s not hard to see why. Crook’s detailed, tightly composed, technically polished canvases are full of dreamy, surreal otherworldliness. Every sumptuous texture is lovingly rendered. The rich palettes are seductive and hypnotic.

There is a lot of the feeling of surrealists Dorothea Tanning and Leonora Carrington – a kind of idealised and romantic childlike femininity –in Crook’s work. An indefinable historicity permeates her paintings with elements that could be eighteenth, nineteenth, twentieth or twenty-first century. Unmistakably New Zealand, native birds and poignant landscapes anchored these vignettes of elaborately allegorical dresses and furniture to place. It’s fantasy. It’s science fiction. It’s magic.

There seemed to be something in the water at this time. Dunedin was in its epic dark romantic phase, and Christchurch was rediscovering its Victorian gothic as a kind of sophistication. It was a distinctly South Island atmosphere.

Bill Hammond had been around a while, and Ilam alumni like Séraphine Pick, Saskia Leek, Shane Cotton and Tony De Lautour were just beginning to find traction. In 2003 Crook was the William Hodges artist fellow in Invercargill, and eventually, after a residency in Beijing and a stint in Berlin, Crook’s family moved back to Christchurch, or rather Diamond Harbour.

The 2011 Canterbury earthquake destroyed their home, so she, Brian, and their young daughter Rosa, picked up sticks and relocated to another, equally atmospheric and unreal place – Joshua Tree in California. (Coincidentally it’s just a three-and-a-half-hour drive through the Mojave Desert and across the state border into Nevada, where last month’s takahē guest artist Matthew Couper is based. They’ve both gotten to know each other.)

Crook has become something of a hot commodity among collectors in Los Angeles, and the high desert has replaced much of the temperate New Zealand rainforest in newer paintings like Everything is Dreaming #2, Voices by the Rowboats, and the gorgeously named Sequin Night in the Darkness of the Blood.

It’s impossible to deny that Joshua Tree with its coyotes, cacti, and rock/country pedigree, agrees with Crook, though desert minimalism doesn’t seem to have dampened her indulgent and unapologetic maximalism. The paintings seem considerably more spacious, the skies more psychedelic. There is more, I think, overtly religion-inspired (religious is probably not the right word) imagery.

In The Nine Fold Underworld there are figures that might be called angels, though some seem of a Buddhist bent and the rest resemble the more bizarre Victorian fairy painters than a traditional Christian would be comfortable with – though no less strange than Rubens’ Fall of the Damned (c. 1620)

(I saw the Reubens one rainy summer day in Munich in 2008 and didn’t know what to do with my hands) or Bosch’s Fall of the Rebel Angels (Between 1508 and 1516,) which I saw the same month as the Rubens, though peering through a hell of a hangover, in Rotterdam. Both pieces of art that I consider shaped my tastes, or at least my outlook.)

The Nine Fold Underworld supplies the title for the project it is part of, a collaboration of painting and soundscape created with Brian that featured at the Pūmanawa Room at Christchurch’s Art Centre in May this year. Given the mysticism and sheer theatricality of Crook’s paintings, it’s not surprising there would be some kind of synergetic frisson with the Catholic Baroque. I had always thought of Crook’s paintings as Wunderkammer, cabinets of curiosities.

In these new works reliquaries – opulent containers for the protection and display of saintly relics – feature prominently: Reliquary of the Bat, Reliquary of the Bee, but instead of human saints it’s a souped-up religion, or at least mystical spirituality, of Nature. That’s Nature with a capital ‘N’ in all her pomp and glory, not the abused and disempowered scientifically describable phenomenon, broken but unbowed. That bat that hunts in primal night and the bee who toils by day.

There’s even one work, House of Occlusions, which looks like an altar setup for a particularly surreal deity with a passion for antique oddities. The centrepiece of this tableau is clearly another reliquary – or perhaps a monstrance, the special kind of reliquary where the Eucharist is kept – though the relic it contains appears to be a pudendum that looks passingly like an orchid.

There’s a reliquary containing an egg in the 2017 painting To Know Not What, in the back of a little wooden boat along with a strangely fishy multi-tiered cake. The boat, also named the To Know Not What, is steered by a goat, and I’m reminded a little of the notion of the scapegoat in Leviticus 16 that is sent out into the wilderness carrying away the sins of an entire community.

So, with that in mind, perhaps I should start thinking of Crook’s paintings as reliquaries for things too mysterious and powerful to be let loose in the mere mundane world of mortals, their spiritual glories made manifest in lush visual excess.

Andrew Paul Wood