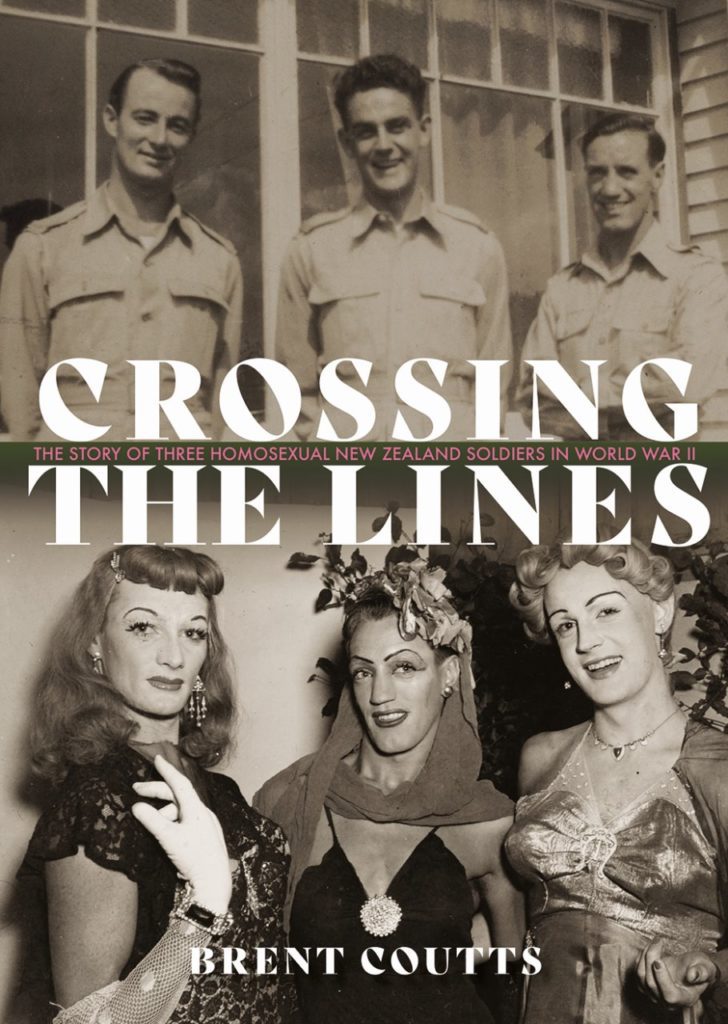

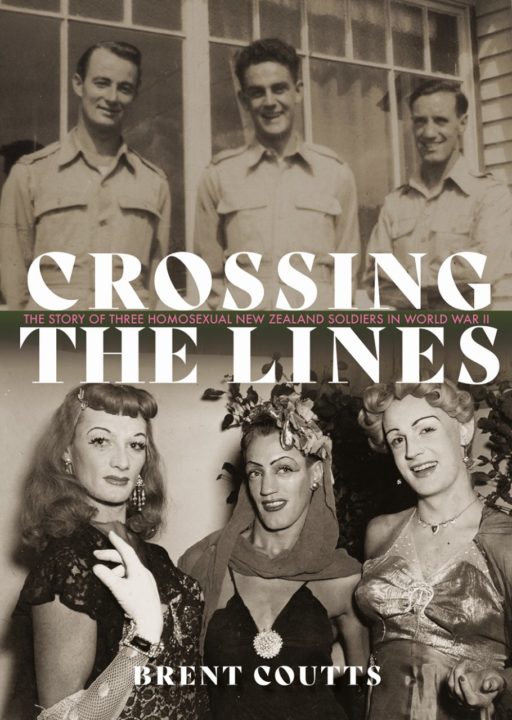

Crossing the Lines

Crossing the Lines: The story of three homosexual New Zealand soldiers in WWII by Brett Coutts. Dunedin: Otago University Press 2020. RRP: $49.95. Pb, 336pp. ISBN 9781988592381. Reviewed by Andrew Wood.

It wasn’t all that long ago that a history of LGBT life in New Zealand would have been difficult to publish. Indeed, New Zealand’s Homosexual Law Reform Act only passed in 1986 with considerable friction; well behind decriminalization in the UK with the Sexual Offences Act in 1967. Only in the last twenty years or so has it been possible to tell those stories in a positive and affirming way.

While there are a handful of academic studies that predate it, the first NZ gay history for the mainstream commercial market was almost certainly Chris Brickell’s Mates and Lovers: A History of Gay New Zealand, published by Godwit in 2008. For a broader summary of the field, one may consult Tony Millet’s bibliography Homosexuality in New Zealand: 1770 – 2012 (2013), the online version of which is periodically updated. Australian LGBT history is a more developed area of research, along with the UK and USA.

Brent Coutts’ Crossing the Lines is a worthy contribution to an expanding field of NZ LGBT history, exploring the lives and experiences of three ordinary men who were soldiers during the Second World War: Harold Robinson, Ralph Dyer, and Douglas Morison. Coutts fleshes out a detailed picture with a decade’s worth of interviews and archive dives. Despite an obvious need for discretion – an informal ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy was observed – it was a surprisingly open existence, though not universally pleasant for homosexual men.

The subject has been a struggle as language and identity evolve. I’m going to try to avoid terms like “gay” and “queer” because an older generation of men didn’t identify with them in the way we do now. “Queer” is particularly problematic as a former slur – in recent memory it was the worst thing someone could be called, someone to be ostracised, and frequently foretokened a beating.

Homosocial spaces in the first half of the twentieth century tended to be more forgiving and accepting of homosexual activity. Contrary to popular wisdom, this also included the military where there was a tacit understanding among command ranks, often used to it from boarding school, that it contributed to morale and esprit de corps. As Coutts found, going through thousands of court-martial files, there were surprisingly few for homosexuality. Many aspects of traditional gender roles simply didn’t apply – the manliest of men were expected to cook, sew, and clean.

Robinson, Dyer, and Morison had relatively well-adjusted lives and what used to be called a “good war”. They found a niche for themselves in Kiwi concert parties in the Pacific and North African campaigns performing en travesti as female impersonators – shades of It Ain’t Half Hot Mum. But prior to the late 1980s, camp could be a shield, camouflage and a sly protest of the mainstream as much as an affectation.

Later generations might regard that as self-parodying liability, ignoring the deep historical roots of such coded performative behaviour. It’s a different treatment to previous histories of New Zealand concert parties where the subject of homosexuality barely registers, like Sing as We Go (1944) – understandably – and Whistle as We Go (1995) – which this side of the watershed had no excuses.

The highest profile and most engaging of the three, Robinson was a ballet dancer from Dunedin who, in the 36th battalion, became batman (military valet) to Major and future New Zealand Prime Minister John Marshall. In Auckland, shortly before he left for Egypt, he became friends with lesbian burlesque icon Freda Stark – for more about her see Diane Millar and Dianne Haworth’s excellent Freda Stark: Her Extraordinary Life (2000).

Stark sent food parcels to Robinson, and when he returned, they married, although the attempt at a romantic relationship petered out after a few months. Harold won a soldier’s bursary to Sadler’s Wells and went to London, where Stark eventually joined him. All three men ended up living together in London, but only Robinson decided to return to New Zealand.

What I like most about Coutts’ treatment of the subject is that there is no obligation to centralise modernist narratives of transgression or postmodern ones of trauma. Coutts isn’t trying to push his wheelbarrow over an agenda. These three men are very much themselves, social beings in communities, and he respects their worldviews and experiences for the human stories they are. Coutts also has a knack for using the trio to tease out other homosexual narratives and identities in the armed services, some known and some new. Of particular note is the surprising revelation of the existence of Brigadier William Dove (1894-1976).

Dove was an Officer Commanding Administration and Base Commander during the Second World War, a Military Cross awardee, and although married, a closeted homosexual man, he acted as something of a protector and patron of other homosexual soldiers. After the war, his favourites would often be invited from around the country to his Taupō bach for clandestine orgies. Details like this shine a new light on the sexual and LGBT history of Aotearoa. To be honest, I’m surprised there hasn’t been more of a public furore over his outing, or at least some gritted teeth and grumbling from the RSA.

Coutts constructs his braided narratives with consummate pacing, leading us through these lives by the hand, and with a measured tread. The stories have the gradual development of a Polaroid and are told with a minimum of sensationalism or misery porn. That’s not to say it’s unrealistic about the homophobic and patriarchal tenor of the times. These are normal people with complicated but unexceptional lives making the best of it.

They are, in other words, us, and in a community that has a byzantine relationship with lineage, family, fraternity and father figures, it’s quite nice to discover our gay grandfathers.