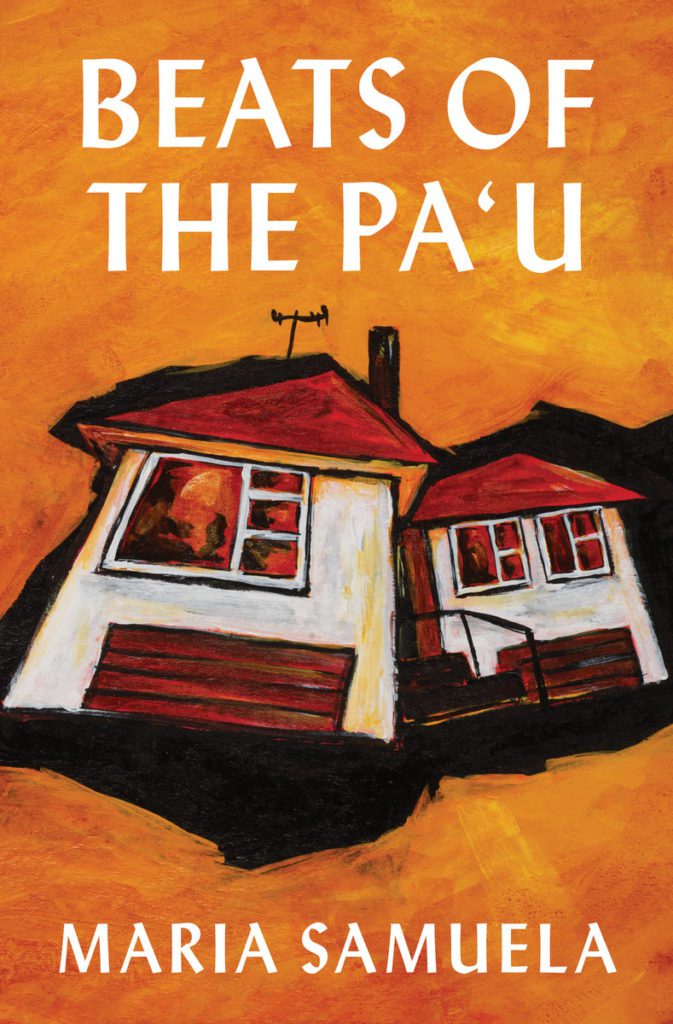

Beats of the Pa’u

Beats of the Pa’u by Maria Samuela. Te Herenga Waka University Press (2022). RRP:$30. Pb, 152 pp. ISBN: 9781776920037. Reviewed by Sarah Maindonald

Kia orana katoa toa!

As we hear the actual ‘beats’ and rhythms from the Pa’u, Maria Samuela artfully captures the various ‘beats’ of a community, diverse, imperative, sharp, seductive, surprising.

Love Rules for Island Girls, Love Rules for Island Boys and Love Rules from Island Mama all have their own unique rhythms and yet resonate cleverly with each other with subtle variations of the same community ‘beat’. The first sentence of each of these stories starts with a conditional ‘If’…there are always community considerations!

Love Rules for Island Girls: ‘If he’s an Island boy make sure he’s not related…and find out who his mama is.’ (p.95)

Love Rules for Island Boys: ‘If she’s an island girl find out who her brothers are…worry about the women in her life: her mama, her aunties, her sisters and cousins.’ (p.44)

Love Rules from Island Mama: ‘If you want the good husband to marry, make sure he not the bad man. To know he not the bad man, see that he good to his mama, This the most important thing.’ (p.108)

Each of these reveal the differing perspectives and priorities of Island Girls, Boys and Mama but the common rhythm of the sentence structure and the weaving of a collective sense of hearing the same narrative from different angles gives us a rich sense of how relationships are navigated and the values and skirting of risk that occurs specifically with the power of the mama.

Maria highlights that, as parents, we all want the best for our children, and here, that means, we want them to have a good, respectful partner. Maria’s humour, however, is her own and leaves us under no illusion around the values of the Island Mama:

‘If you want the good wife to marry, make sure she not the cheeky girl, see how she treat your mama. This the most important thing. When she come to your mama house and she eat like the picky picky bird she the cheeky girl. If she leave the chicken bones on the plate with the chicken meat still on the ones, she the cheeky girl. If she wipe the coconut cream off the coconut bun because she say it make her the fat girl, she the cheeky girl. And probably she too skinny. Don’t trust the skinny girl. She the cheeky girl to.’. (Love Rules from Island Mama p. 108-111)

Some of the Beats of the Pa’u are sharp. Bluey for example has an uncomfortable choppy rhythm one that that jumps from character to character, speeds up, slows down then takes unexpected turns.

The usual rhythm of Rosie’s afternoon is disrupted when her father gives a ride to an old mate he picks up at a regular visit to a tinny house:

‘Faarr bro!. This is a flash car, my bro. Look at these things, bro. Electric windows, bro!’

The window behind me went whirr then stopped. Whirr. Stop. Whirr. Stop

‘Gets us from A to B. That’s all we need. A to B’ Dad turned the radio down.’ (Bluey, p. 51)

Rosie is uncomfortable, and yet the tension of the story resolves somewhat when Rosie finally sees the blue of his eyes, seeing past the gap where his two front teeth should have been, his dreadlocks like ’dirty ropes’ and puts aside some of her concerns about her fathers connection with this man who also knew her mother. Bluey was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize acknowledging the mastery shown in creating an entire narrative with multiple characters and memories lived through a random conversation in a short car trip.

The final and longest story in this collection shares the beats of a Rarotongan mass, a community dance and tangled relationships. It holds the title of the collection as the beats herald the ‘sound of home’(p. 128.) Anyone who has been to church in Rarotonga will recognize Terepai’s voice (one of the aunties) as

‘her voice meets the wooden slats of the ceiling…like a rooster at the break of dawn beckoning the angels….’ ( Beats of the Pa’u. p. 113)

and yet we are in Porirua. This story is full of the tensions of transitions from the influence of the church and traditional expectations, particularly of girls to urban living in New Zealand.

Maria is courageous in her minute exposures of the tension between the desired piety of the congregation and their inner preoccupations played out in Terepai’s family and her daughter’s as yet undisclosed pregnancy. Terepai’s own experience of abandonment and bringing up her daughter by herself shapes her response to her daughter’s situation leading to an unexpected and poignant conclusion.

There are glimpses of Maria’s talent in this weaving of old and new, island and urban, older and younger, cynicism and hope. She crafts poetic lines, for example:

‘I am woken in the morning in that time between night and day, when the spirits of our ancestors whisper in our dreams.’ (p.144)

contrasting with the harsh reality of the police showing up at 5:00 a.m in Dawn Raids style.

In this, her first collection has artfully explored the impact of religious and colonial narratives on gender roles and sexual expression from multiple perspectives through the eyes of island girls, boys and mamas and expands this in each story to include vignettes of life for those from Rarotonga and the Pacific who came to Aotearoa in the 50’s.

The Beats of the Pa’u are undeniably current and yet shaped by the rhythms of pa’u in their Rarotongan home.

Meitaki mata Maria.

Sarah Maindonald is of Fijian Indian and Pakeha descent, born in Aotearoa. I identify as an Asian Pacific New Zealander who walks comfortably in Te Ao Māori. I have always loved writing but started writing more formally when I joined the Hagley Writers’ Institute in 2010. I am now a member of Fika, a collective of Pacific writers in Otautahi, Christchurch.