Bad Archive

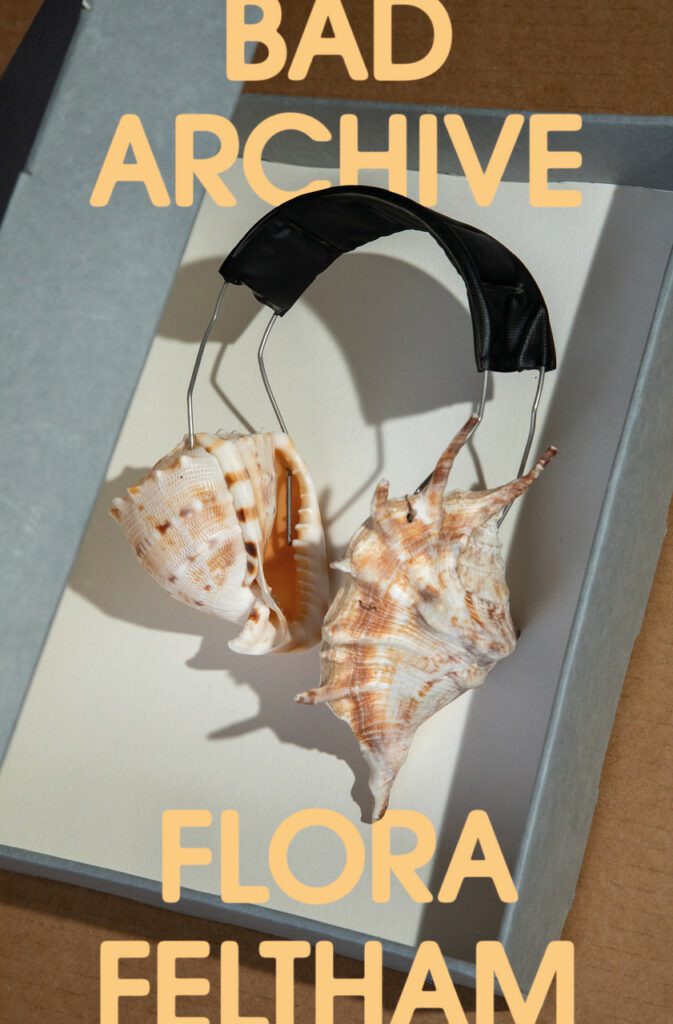

Bad Archive by Flora Feltham. THWUP (2024). RRP: $35. PB, 256pp. ISBN: 9781776922062. Reviewed by Hannah Patterson.

Personal essays take many different forms. They can be fragmented and vignette-y (see: Blueberries by Ellena Savage and Tinderbox by Megan Dunn), they can border on poetry (see: Bluets by Maggie Nelson), they can lean into argument and theory, criticism and sometimes journalism (see: Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino). But it seems to me the most common form in New Zealand is the personal essay collection as a series of memoir-like stories, chronological order not necessary. Reading these can feel like meeting a person at a party, where they proceed to tell you all their most interesting anecdotes and opinions. This is incredibly taxing if the person is uninteresting. But if the reader is lucky, they are in the hands of a good storyteller.

Flora Feltham is a good storyteller. She holds the story with gentle hands—13 stories, to be exact. Her debut book, Bad Archive, came out in July from Te Herenga Waka University Press. I still think about it, some days, when I look at the sky. I think about what Feltham meant when she said she saw the world differently after learning to weave.

As a physical act, a metaphor, and a way of seeing, weaving is at the heart of the collection. ‘It has no right side and no wrong side,’ Feltham writes in “The Raw Material,” ‘its uses are both sacred and mundane.’

In “The Raw Material,” Feltham’s most intimate and impactful essay, she pulls two threads together—the story of when she first learnt to weave: ‘When I weave, I discard language … All words dissolve from me,’ and the story of a moment of crisis in her marriage; ‘The problem was that Pat had kissed someone who wasn’t me.’

Back and forth, we turn as Feltham deftly intertwines two stories about the great loves of her life. One, a tale of discovery, growth, and creation. The other, a story of coming apart, disintegration, and disentanglement (and eventually, coming back together). This essay is the most personal in the collection. Feltham learns her husband has cheated on her and she depicts this vulnerable time in their relationship in a close, detailed way. They are both in the process of being transformed.

An essay like this which is so close to the author is challenging to review. There exists the substance of the story—in this instance, and reductively, a relationship in the aftermath of cheating held up to the microscope, the reader brought along the way through personal revelations about addiction and relationship therapy. A story like this will naturally be compelling. At the level of lowest effort, it will at least be salacious. Gossip. But a really good essay is more than this, and Feltham achieves that, transcending rather than merely utilising the shock of this deeply personal moment in her and her husband’s lives.

This is a tension her essay must confront, and questions around the ethics of the piece float in the back of my mind as I read it. To be clear, I felt that the revelations in “The Raw Material” were treated with sensitivity. But I felt conscious of this need for great care and precision as I read—like watching a surgeon perform a risky task, hoping they don’t needlessly rupture the heart.

And Feltham is nothing if not meticulous. Each word of each essay feels carefully chosen. Her gaze is at times unflinching and unsentimental, but it’s never cruel. There is an openness to it, which comes across particularly in “The Raw Material,” the burning story, but is also apparent in the more outward-looking essays.

In “Bogans of the Sky,” Feltham turns her gaze towards the gulls that flock at the Brooklyn landfill. I loved this essay for how much it loves those birds. I loved it for Feltham’s ability to scrutinise something without scrunching it up. Instead, she spreads it out and looks closely at it, to see the specificity. She’ll do this with her relationship with her mother and she’ll do it with a Meccanoman convention up the coast. Feltham shows us how looking, really looking at the detail of something is a lot like the practice of loving. This is the component that makes her stories akin to weaving, sacred and mundane.

It is this open and curious eye that, to me, holds the collection together. The reader’s curiosity is challenged to keep pace with Feltham’s searching gaze. In the strongest essays, Feltham’s attentions feel totally natural, unstrained. There were only a handful of stories—“Dekmantel Skeletons” and the two final essays, both taking place at conventions—where I wanted slightly more: to stare longer at what lay at the heart of those stories.

But most of the time I swept through the collection. Feltham writes so beautifully, clearly and honestly. The world at her pace, on her level, is one in which deep care and gentleness are not compromised by what is hard and ugly, but made real. I feel lucky to see the world through Feltham’s words.

Hannah Patterson is a Chinese and Pākehā writer living in Wellington. She has an MA in Creative Writing from the IIML and is currently working on a collection of poetry. You can find more of her writing in The Spinoff, Turbine | Kapohau, Spoiled Fruit: Queer Poetry from Aotearoa (Āporo Press, 2023), and bad apple.