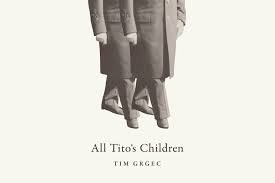

All Tito’s Children

All Tito’s Children by Tim Grgec.

Wellington: VUP (2021).

RRP: $25. Pb, 96pp.

ISBN: 9781776564286.

Reviewed by Jessie Neilson.

Tim Grgec’s Yugoslavian heritage is the focus of his debut poetry collection. He has masters’ degrees in English literature and creative writing from Victoria University and won the Biggs Family Prize for Poetry (2018).

In All Tito’s Children, Grgec selects a quote by Nobel Prize-winner Yugoslav writer Ivo Andric for one of two epigraphs. Sometimes what can be invented about a person will tell you quite a lot about him, it states. The person at the centre of invention here is former Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman Marshal Josip Broz Tito. He is reimagined by Grgec, whose grandparents fled Yugoslavia in the 1950s.

In seven parts, All Tito’s Children gives voice to two siblings: Elizabeta and Stjepan, as well as to Tito. There are secondary resources, such as invented newspaper clippings and theatrical dialogue. While the overall content is slight, it is more than enough to leave hints of both the tyrannical leader and of the pervasive fear running through a people with time-worn, rural farming traditions, up against a collision of politics and egos.

While it is called a poetry collection, Grgec’s work strays between free verse poetry, prose, speech, theatre scenes and public addresses. There are also lists and encyclopaedia entries, claiming objectivity. Sometimes there is prose of generous length, while at other times Grgec conveys an atmosphere or scenario with the briefest line or two. Short or single stanzas of poetry are a frequent feature. A lot is metaphorical; history plays out on an ancient, supernatural landscape.

The collection opens with a threat from one authoritarian leader to another, Tito to Stalin. It is 1948, and the socialist leaders are sparring. Yugoslavia is breaking free of Russia, a superpower which had dominated, one which personified, had ‘demanded to sit at our bedside with a cloth smothered heavily’ (p.31). With freedom, and an emergence from a fog of foreign occupation, comes a new dawn dew. Feet can begin to feel the ground beneath them. The image is of snow thawing, like polished spectacles, and a clearer vision.

Following his last meeting with Stalin –appetites sated with a cloggy combination of heavy soup and glasses of vodka, good to keep the bitter cold out, Stalin reveals himself to be the fierce abomination within – Tito seeks self-determination. And on heralding himself as his country’s President in 1953, he proclaims that the ‘truth will lead us’. They will now be free from the shadow of the USSR, previously only ‘darkening the circles under my eyes’ (p. 14).

According to Tito himself and to the fervent statements of the local people, they are grateful for his intervention. His portrait hangs proudly in modest homes, where people keep the faith and superstitions of old. As one of the young spokespeople, Elizabeta refers to him as the ‘brave, handsome’ leader, there to chase fears away. A God-like figure. Clippings of him adorn her walls.

Brother Stjepan is less effusive in his praises, feeling his obligations as a male. He knows that military service is universal. He will follow centuries-old paths into ethnic feuds, farewelled with symbolic gifts from his parents: a book strung together by hand from his mother, and a cut-throat razor from his father (p. 53). He is familiar with war stories of soldiers trudging through the snow-drenched Carpathians, where the crunch of dead leaves can mean the death of a human.

Heroism and sacrifice run throughout the narrative of this country. Stjepan, an avid reader of history and non-fiction, is told “We are all something and someone” by Josip Smodlaka, a founder of the country (p. 27). Defence of the Fatherland, the supreme duty.

Tito’s voice broadcasts from Belgrade radio stations: “Comrades, citizens, brothers and sisters! I address you, my friends…” (p. 31). Poetry here more closely emulates prose, in form and reception. Such inclusion cannot fail to draw together all his country’s people under his wing, all his children, for whom he will ostensibly care. The Yugoslavs reputedly had big families, with every ninth child traditionally and symbolically taking Tito as godfather. Tito writes letters to these children, in a performance of pastoral care. They are, metaphorically, his children and like fledglings lie scattered, before him.

Therefore, by extension, Grgec, and also his immigrant grandparents, are also the children of Tito. Even abroad, they are forever connected. Again, we are reminded through Tito personally and the Constitution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1953), that high treason is the greatest crime.

In the bombastic language of breaking free from the ‘shackles of our Russian masters, those impregnable rogues’ (p. 37), one dictator is replaced with another. Or, as is hinted here, a dictator plus his body double, for a hapless victim is found to emulate in appearance, temperament, and utterances, the great man himself.

In Grgec’s third section, ‘Emergence from the Fog’, part of this movement towards clarity entails replication, invention, and duplicity. It will come whatever the cost. The scene takes place in a generic, totalitarian-era hospital building of grey walls and grey concrete. The form is a scene from a play. It is 1946 and the victim is about to be operated upon by a cosmetic surgeon. Tito hovers in the wings. The victim is given verbal affirmation that his family is safe, but it is lies, for they, like many others, have disappeared, have been disposed of.

In this light, Tito no longer radiates kind fatherliness; his ‘hardened stare’ and the familiar stern expression sits above his strong jaw, as if he is evaluating the whole world. The wider Balkan states are struggling with persecution, torture, and torment. And as Elizabeta slowly comes to awareness, forbidden stories of their leader circulate throughout the countryside. While his name had been on their lips for years, now pictures of him on their blackboards grow eyes (p. 23). People are questioning, albeit secretly, and fearfully.

Tito, like his country’s people, was born of peasant stock, and of questionable birthplace, birthdate, and even name. It is claimed he has a strange accent, one which cannot be pinned down. He may be of the land, but still, he fumbles over his own mother-tongue.

He reinvents himself many times, Tito being only one of his pseudonyms. He has multiple names in forged passports, and speaks many tongues, digesting the world news in many different nations’ papers. As one writer records, ‘the police would never find us behind our invented selves’ (p. 59). Like Andric’s epigraph, this rings true. For who really was Tito, and what kind of legacy would he leave in his country? What alternative modes of living would he establish through communism?

Meanwhile, generations of people, from young to the very old, were following the commands of the seasons, tilling the land, harvesting and planting. The everyday person is a product of the land and of folktales, where superstition and tradition carry much weight. They were ‘rummaging about the earth as our village had always done’ (p. 20), Grgec’s grandfather, likewise. In the photograph adorning the back cover, his grandfather is standing in a fertile field, farm implement in hand. As if to say that, under Tito, nothing and everything had changed. The political and the personal, layered heavily upon the land.

They were weaving beautiful baskets out of willow strands, the colour of mottled apples ripening, in cottages by the light of a candle. They were checking on their crops or recalling secret chicken soup recipes handed down from baka, grandmother, to the younger generations. Now, however, there is an added but necessary surreptitiousness, with farmers hiding crops from authorities.

The soil is rich for potatoes, fertile ground, as the rivers Mura and Drava flow on through the decades, the smell of silt and sand enclosed. Yet there is apprehension. Villagers reap wheat out of an illusion of movement, but “progress” is questionable. While toiling with a scythe, a man conjures up the futile dreams of inventions which will never succeed.

The landscape takes on a shade of horror: the rows and rows of clustered beanstalks as if out of a fairy tale, and the snapping of ‘bony fingers off trees’ (p. 45). Much is insidious and feels as if it could come to life. The seeds planted are yielding huge masses of doubt. Stjepan, especially, feels this as he finds himself looking towards war, where dangers can hide beneath the seemingly peaceful undergrowth. From out of the snowy landscape, either a dream or a nightmare, comes the image of thousands of clutching hands. These may be the hands of dead soldiers, echoing their loss, or, as macabrely, reaching to greet.

Ironically, while foreshadowing a wider world of repression, where ethnic tensions must be contained, this treatment of the landscape also harks back to myth. In this mythical setting are large trees growing too close together, in the province of Pannonia, and birds with tiny human hands and feet. They could lead a person deep into the forest. This grotesqueness is echoed both in the elective doppelganger of Tito, embodying the idea of stitching and cutting and sewing, and in Tito’s chosen reading material, The Art of Oratory, where the narrator claims, ‘a team of surgeons permanently fixed my head on backwards’ (p. 66).

The human form is no longer sacred, nor even truly dead. In this new world, a dead farmer wanders out of his grave to check on frost-blackened tomatoes, which are succumbing to rot just like their human counterparts. He carries his rib bones in his hands, an unexpectedly poignant image (p. 77). The pace has picked up from the early, optimistic days of Tito’s reign. Here we reach the ghoulish end, where the body of the ordinary person joins the earth.

There is blackness, sacks over heads, secret police. Many of the deaths are violent. In more of Tito’s reading material, this time Jacques-Louis David: A Life, it is written that political deaths are the most painful: corpses are buried alive, where one can paint a cadaver with the expression of a breathing man (p. 67).

Old gypsies tell fortunes, predicting whether young men will return from fighting. Chickens have their necks broken: in savage standard procedure. Reading material details the cutting out of tongues against traitors throughout history. One should ‘enunciate as if you’ve swallowed a tray of scalpels’, where each tongue is grasped as if a postage stamp (p. 68).

The landscape, at its best, in a cynical Gallery of Dreams becomes a canvas the colour of factory smoke (p. 70), bitingly poignant when it is claimed the ‘unimagined life…is…not worth living’ (p. 37).

Meanwhile, Tito tends to his canaries as he reforms and represses. He arrives at work, when dawn is ‘emptying its pockets’ (p. 33). He has optimistic plans for himself. He would like to build his own locomotive, with blue silk and velvet, and eat luxuries as the train moved towards ‘an Adriatic spilling into the open Mediterranean’ (p. 42).

Though said to have an ‘immovable brow’, he remains unable to look his surgically-produced double directly in the eye. Tito too had been a fighter, familiar with the sound of shrapnel and of bayonet to bone, scenes of injuries perhaps not so different from the scenes in the hospital of his making. The flickering lights emphasising that all is not what it seems, and not all meets the eye. Much happens by the light cast by lamps in homes and haunts, and much is hidden in the shadows. New identities are being melded.

As Stjepan journeys off to the unknown, his sister struggles to understand reality through reading. She had read Andric, hoping to get to the heart of a person, to reach meaning. Yet, when she read his work, it did not occur to her that his characters were ‘bound by ink, by paper margins’ (p. 26). Tito too is inventing himself with a cult of personality and opening up his country to the world.

When Elizabeta catches her last glimpse of her brother, it is not through Tito’s ‘clearer’ vision: his face is ‘blurred white by the morning glare’ (p. 81). It is a world of partial sight and lack of direction. Who knows, outside of this age and time, what the atmosphere was like for the common townsperson, with their ‘benevolent dictator’.

All Tito’s Children, or many of them, take flight from this reign: with some of these immigrant wanderers even establishing new identities in New Zealand. The last poem in the book pays tribute to both lands, Yugoslavia and Aotearoa, where Lyall Bay, from 1959, is the new home. The narration may be both that of his own voice, and that of his grandparents. ‘My shadow unpins itself from my body and wanders off into the night’ (p. 91).

In this vivid set of imaginings with a strong personal connection, Grgec outlines a world where identity for these children of Tito is as uncertain as opinions and evaluations of the leader himself, where shadows and bodies leap beyond themselves, shedding and reforming.