Paul McLachlan: Layers of Time and Space

At just 9 years old, Eastern-Southland-based artist Paul McLachlan’s eyes were opened to the potential of art by the modernist masterpieces on display at the Guggenheim exhibition that toured to Dunedin Public Art Gallery in 1996. This profound experience ignited a lifelong passion for art, leading him to pursue a career as an artist.

‘This was my first introduction to modernism,’ says McLachlan, ‘an intense experience for someone from a rural, homeschooled background. I remember Chagall’s Green Fiddler and Modigliani’s Student, but more than any single work, it was the first time I understood that making art was something a person could actually do. I have memories of the exhibition—the dim lighting, the audio tracks, the nudes—but I can’t be sure what’s real and what my mind has filled in over time.’

In the years since then, McLachlan has dedicated himself to honing his craft. Now an established artist, he boasts international and domestic awards; residencies including the 2018 Camacho Residency, Portugal 2017, the TextielLab Collaboration Project, Netherlands, the 2016 University of Canterbury Print Studio, the 2016 Surface Arts Residency, Thailand, and the 2013 Large Format Printmaking Residency Venice Printmaking Studio; and many solo exhibitions. Inspired by his immersion in literature, and the vivid imagery and associations of New Zealand’s twentieth century modernist authors, McLachlan describes his style as ‘precise, intensive, and mythic.’ His work reflects a deep engagement with imaginative subject matter and a meticulous approach to detail.

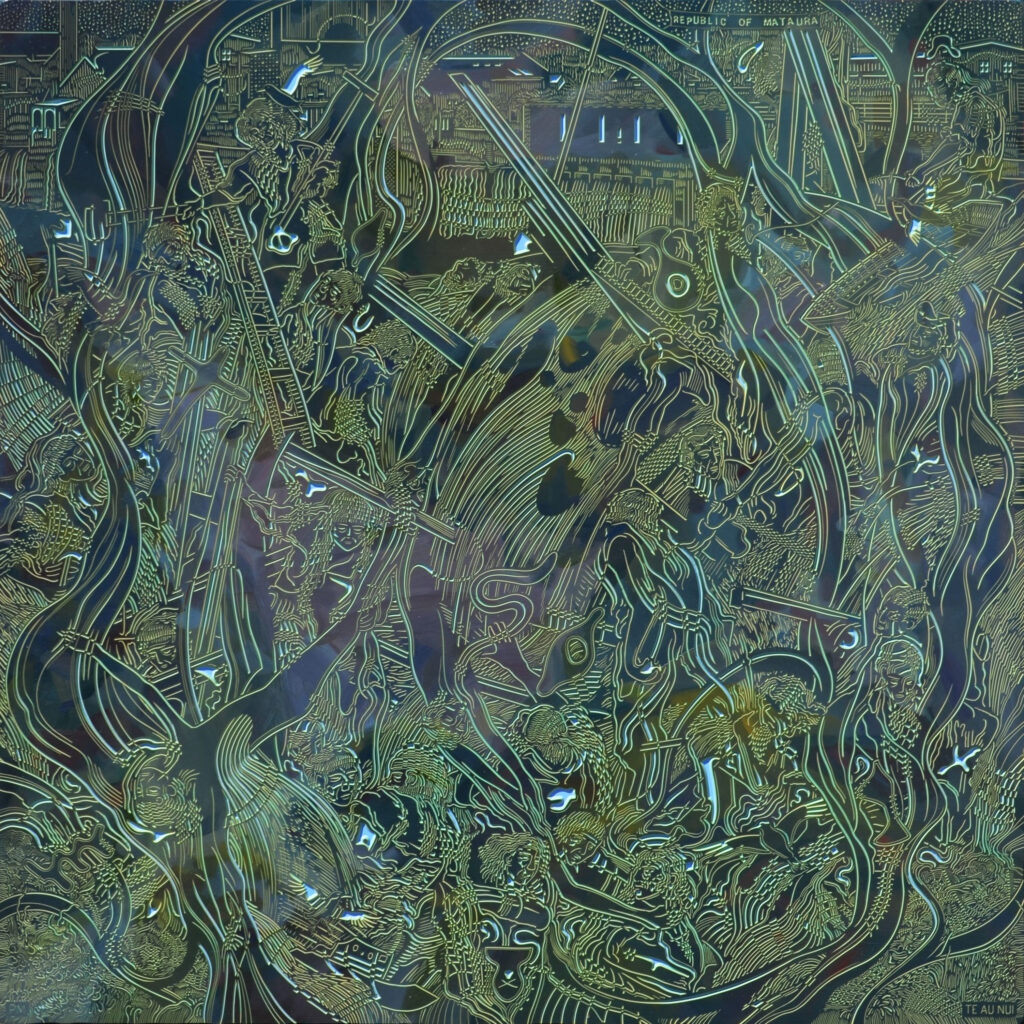

Employing a variety of techniques, including drawing, engraving, printmaking with a digitized mechanical process, shell inlay, and layered painting, McLachlan explicitly references the philosophical concerns of Dunedin poet and Landfall founder, Charles Brasch: what it means to be a New Zealander, particularly a Pākehā, historically and culturally; what it means to associate with a region within the country; and what it means today, with reference to the dichotomies of permanence/impermanence, motion/stillness, sea/land, spiritual/humanist, rising/falling, and architecture/landscape.

‘These contrasts emerge gradually rather than by design,’ says the artist. ‘Over months of evolving the digital composition, the work starts to dictate its own direction and theme, and I emphasise these tensions through material choices. The images feel woven and organic, yet they’re built from rigid, hard-edged lines. Within these structures, surfaces shift—glossy oil or metallic brushstrokes catch the light as you move around them, while rusted surfaces remain super-matte, their oxidized iron particles absorbing light. Sharply engraved lines react differently depending on the angle of the blade, amplifying the interplay between stability and flux, weight and fluidity. This unsettled dynamic makes the works feel as if they are still in motion, continuously unfolding.’

These concerns feed into McLachlan’s thinking about space, context, the land and how they are represented:

‘Being an artist is solitary work, and within this internal life the imagined or remembered can feel just as real as the physical. The landscapes in my work function less as fixed locations and more as layered veils—overlapping impressions of time, history, and perception. Rather than fragmenting space, I build it up through accumulation, allowing motifs to emerge and recede like glimpses through a shifting surface. This idea extends to the materiality—engraved lines reveal what’s beneath, rusted surfaces hold traces of past reactions, and glossy strokes catch the light unpredictably. There’s a sense of instability in the layering, where forms remain fluid, resisting a singular reading. In this way, the landscapes I depict are not just external places but psychological terrains, shaped as much by memory and myth as by geography.’

It is this space ‘between’ things, us and nature, myth and fact, and the ‘disputed ground’ amid these that propels the pertinence of the time-traveling narratives in his work. He presents ‘the landscape not only as a physical entity but also as a gateway to the realms of the spiritual and imaginative.’

McLachlan employs symbolic motifs, particularly native birds such as the albatross and hawk, and the sensations of pattern to startling effect.

‘I’ve always been hesitant with birds,’ he says. ‘They can feel overdetermined as symbols. But they persist. In my earlier work, specific species served as a hook, grounding the image in a version of Aotearoa, especially when the landscapes felt more surreal, like fiery eruptions from swampland. In my later works of the Mataura River and Te Au Nui, birds function more like apparitions or fossils—glimpses of time embedded in the surface. They’ve shifted from being site-specific to something more primordial, impressions rather than representations. Ultimately, they’re always about context and time—whether anchoring a work within an iteration of Aotearoa or fracturing it from known reality.’

Not immediately apparent, but equally as substantial as his symbolism, is the role played by the multiple strata of paint. While at first seeming lightly modulated and essentially a single colour-field, it soon becomes apparent that such simplicity is deceptive: light-strike brush marks and the chromatics of saturated tone and differing hue emerge, actively extending the substance and material presence of each work. Among the qualities of all his works is the stylistic role developed by the recessed lines alongside the visual rhythms and expressive gestures of the rising and falling energized lines.

‘The paintings are built up over weeks,’ says McLachlan, ‘with layers of paint mixed with plaster to reduce elasticity. I work in gradients or stripes, weighing the works to track accumulation so I know when to change colours—on average, a 120cm² piece holds around 5–8kg of dried paint. I suffer from horror vacui and am drawn to all-over painting, creating an exacting intensity that emphasises surface flatness. The more lines I engrave, the more the underpainting reveals itself, producing an excavation-like process where layers interact. These strata function geologically—cuts through the surface that expose time. I think of them as large tablets, where paint becomes earth or sediment, inscribed over time. I use a modified CNC router, which runs constantly for up to eight days to engrave a single work. It’s an intense, relentless process—highly precise, with no room for error.’

McLachlan’s most recent work is very much context-dependent on his home and studio in Mataura.

‘Mataura’s name means “red eddying,” a reference to the iron-rich waters that stain the riverbanks,’ says the artist. ‘Here, natural and industrial histories are inseparable—the orange-hued sediment blends with rusting steel and decaying clay bricks at Mataura Falls. My studio sits within the Mataura Paper Mill estate, built directly on the falls—Te Au Nui, meaning “big swirling waters.” Once a significant mahinga kai (food-gathering place), the falls were dynamited, their waters redirected through hydro-races to power factories and turbines. This layered history is central to my latest works, which treat the site as an inscription—an evolving record of human intervention and natural process, an intersection of industrial power and natural power. Using acrylic and rusted iron paint, I engrave the surface with fine blades, revealing fossils, apparitions, symbols, and woven patterns. These marks act as a kind of palimpsest, exposing distinct strata of time and psychogeography. The rust itself embodies transformation—materialized time, shifting yet static—further embedding the work in the changing landscape.’

An exhibition of this work, Te Au Nui—Big Swirling Waters, was shown at the Eastern Southland Gallery in Gore in 2024.

Paul McLachlan is a multidisciplinary artist from Mataura, Southland, known for his innovative fusion of painting and engraving techniques. His work often explores themes of interconnectedness between humanity, culture and nature.

Andrew Paul Wood is a Timaru-based independent cultural historian and commentator, art writer, book reviewer, essayist, translator and poet. He writes for a number of prominent publications in Aotearoa and Australia. He was the co-editor and translator with Friedrich Voit of the collection Karl Wolfskehl: Drei Welten, Three Worlds (Cold Hub Press, 2016), Dunediniad: A Psychogeographical Ode (Kilmog Press, 2018) and The Sonnets of Walter Benjamin (Kilmog Press 2020). His latest book is Shadow Worlds: A History of the Occult and Esoteric in New Zealand (Massey University Press, 2023).