Symphony of Queer Errands

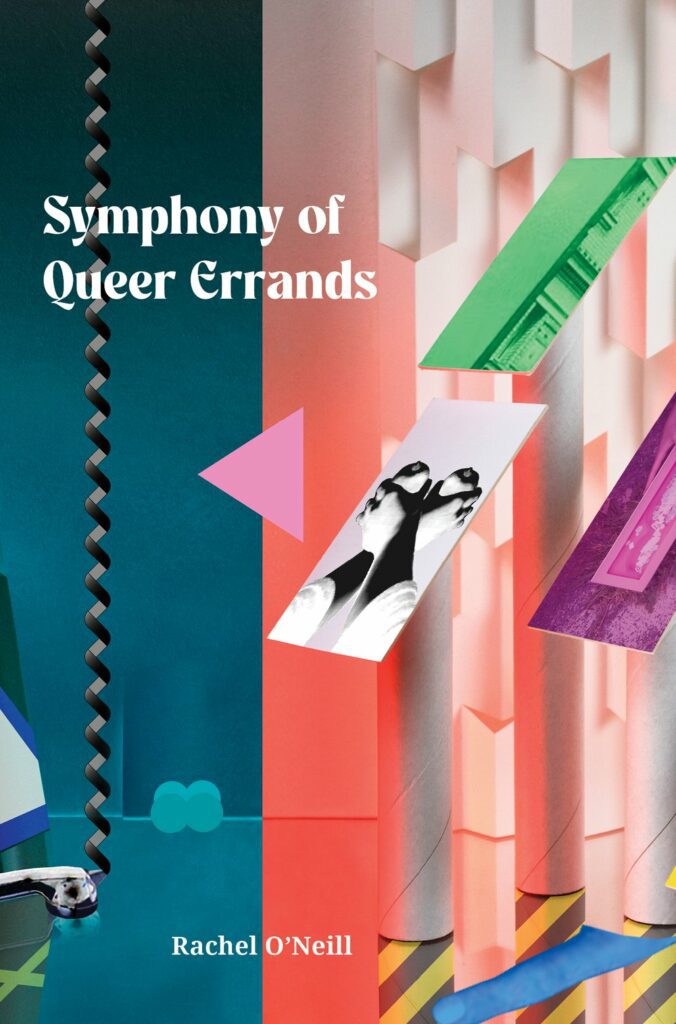

Symphony of Queer Errands by Rachel O’Neill. Tender Press (2025). RRP: $30.00. PB, 110pp. ISBN: 9780473725754. Reviewed by Sophie van Waardenberg.

Symphony of Queer Errands, the third book by filmmaker, writer and artist Rachel O’Neill, is impossible to describe concisely. Made up of eight parts, it follows a composer conceptualising, crafting and recrafting their titular symphony, which itself makes up the final section. It’s part prose, part lyric, part score notation—an ambitious, joyful and ever-expanding treatise on life as a queer artist.

Embarking on creating their first major musical work, the composer (Symphony’s main character) actually starts out articulating their ideas relatively unmusically. Their attempt to describe their project to Found Sound—a flirtatious fellow artist they meet in a cave, and whose advice, teasing and companionship are central to the development of the symphony—is an uncertain dithering, sunk deep in abstractions:

‘Well, ah, I’m interested in sampling or, more explicitly, selecting. Like, is it possible to produce an emotionally healing sonic experience that selects from all sorts of frequencies, even normative, and repurposes them, unearthing alternative pulses—whole restorative nervous systems, maybe even conspiring in tactics for deeper root disturbance?! And, when a sound is in any way oppressive or it grows tyrannical, is it a case of mutate or mute, and how?’

Symphony depicts the scramble of an artist’s life: a life of trying, failing, reiterating, and preparing oneself for—and recovering from—criticism. Most of an artist’s time is spent doing something that’s not quite right, just so that, in breaking it down, they can begin to envision what they should be working towards instead. There are glimpses of the beauty in the process, but it’s also a slog. In fact, the first three sections of Symphony are all attempts at a prelude, each ending in feedback and a grumpy, yet uncertain, rebuttal from the composer. The third and final rebuttal reads: ‘I’m not so sure. I’ll keep working on it for a bit. You’ll have to push out the concert date. (Ha! Psych! It is perfect!)’ This cycle of creation, feedback and defensiveness will feel familiar to anyone who has shared their early drafts.

More specifically, Symphony of Queer Errands explores the courage and persistence required to create something on an ambitious scale—a work of art that relies not just on the composer but also on the unpredictable elements of collaborators, including orchestral musicians and, in this surreal setting, the instruments themselves.

This wrangling of diverse and often clashing personalities is clearly introduced in a section titled ‘SOME OF L’ORCHESTRA.’ In compact chunks of prose, O’Neill introduces various fictional instruments, most of which are sentient or require a connection between at least two human beings in order to be played. There’s the Muse Machine, less a discrete instrument and more a ‘collective agency of muses.’ There’s the Brass Narcissus, which ‘undertakes lengthy interviews with its preferred players’ in order to create a ‘full psychological profile’ of its chosen musician. There’s the Harness, a ‘cognisant […] partner who/that happens to be made of straps.’ And there’s my personal favourite, Little Dreamy: a creature held in the player’s hand which ‘emits subtle whines and faint twitches’ but should not be woken abruptly.

Amongst these instruments is the Queer Errand itself, an evasive member of the orchestra, almost impossible to describe, and capable, when present, of ‘rustling up whole quantum ensembles at the molecular level.’

It’s a delicious thing O’Neill prompts us to contemplate: that music is not something to be dictated to its players or forced upon its listeners. Perhaps, rather than a fixed artifact, it’s something alive and sensitive—something that absorbs the moods and intentions of those involved in each stage of its creation. It is changed through collaboration, and each time it is played and heard, it is utterly unique.

Of course, that means the music — and its collaborators—can be unstable, even volatile. In a section titled ‘POST-REHEARSAL DISSECTION,’ the composer attempts to receive constructive criticism from their orchestra after a play-through of their symphony but is interrupted by various self-involved mutterings by players and instruments alike, including unceremonious outbursts by the 9,000-Foot Twit evacuating its player’s spittle. There’s no hope of a respectful collaborative discussion. The symphony has been removed from the composer’s control and become something unruly and ineffective: it’s time, the composer realises, to rethink the whole project.

O’Neill plays with the constraints of the page throughout Symphony. In several sections made up of first lines taken from Francis T. Palgrave’s The Golden Treasury of Songs and Lyrics in alphabetical order, narrow columns force lines into tight spaces where they collide with each other, enjambing strangely and creating fascinating new timbres. The sections of notation—the score itself—are created by lines of punctuation and, occasionally, fragments of text, and use blank space liberally. Though the page is used beyond what’s conventional, in a spatial sense, it’s tempting to wonder whether any other shapes or techniques could have been borrowed from the world of graphic musical notation. Still, Symphony frays the edges of poetry and music, raising questions of what can be translated to the page—and what can be lifted from the page as music.

Because Symphony of Queer Errands is trying to do so much in such a small space, it runs the risk of short-changing a reader who may want to be carried along by its narrative for longer, who’d like to linger with the protagonist as they compose and revise and flirt. Instead, we’re swept from story to symphony quite quickly and left to wonder, as lyric takes over from prose, what might be happening in the concrete world with our musicians, our instruments, our composer and their companion. Disorienting though this may be, the book’s flightiness also makes for an immersive reading experience in a different way. We may not get to settle into the story for very long, but by the time the symphony reaches its finale, we find ourselves sailing along on its harmonic sequence. A ‘chord of a charcoal dream’ shifts to a ‘chord of agricultural favours.’ Then, at last, a Queer Errand appears. What it does, or sounds like, we are left to imagine—faced with a blank page, the reader becomes the symphony’s final collaborator.

Though grounded by the never-ending struggle of existing as an artist and as a queer person in a world that’s often crushingly rigid, Symphony of Queer Errands carries a refrain of joyous perseverance:

‘On a queer errand

to save the happiest song

in the world

from being recruited by the Apocalypse

we learn there is an impossible gathering

of fire in the earth’

Sophie van Waardenberg is a poet living in Tāmaki Makaurau. Her first full-length collection, No Good, is forthcoming from Auckland University Press in 2025.