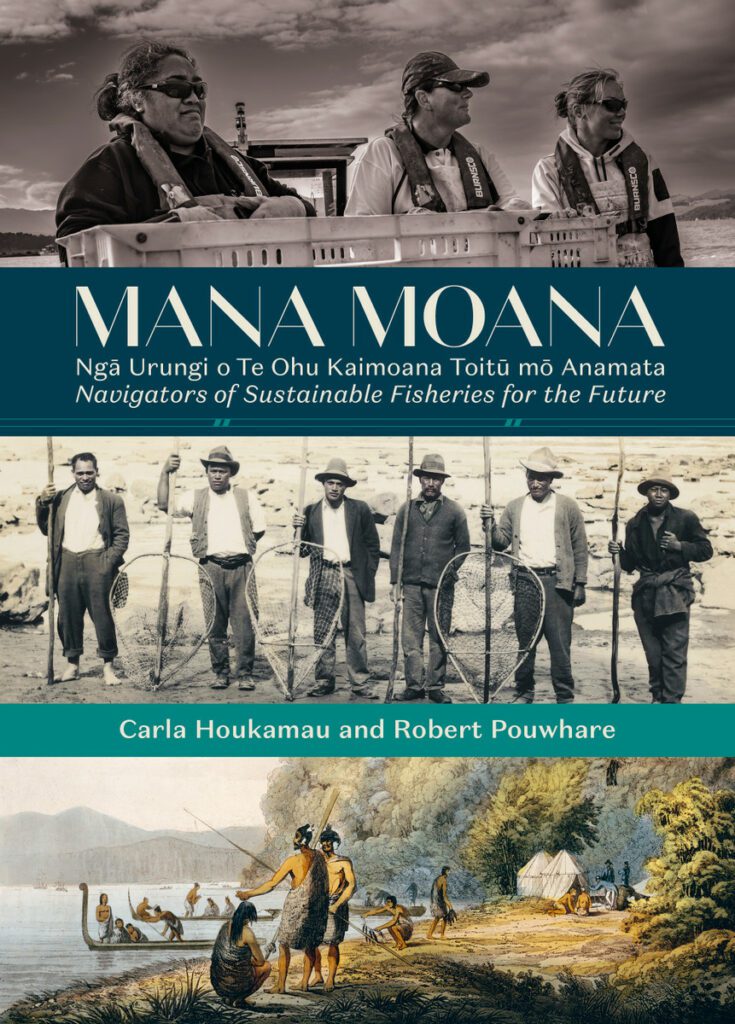

Mana Moana: Ngā Urungi o Te Ohu Kaimoana Toitū mō Anamata / Navigators of Sustainable Fisheries for the Future

Mana Moana: Ngā Urungi o Te Ohu Kaimoana Toitū mō Anamata / Navigators of Sustainable Fisheries for the Future by Carla Houkamau and Robert Pouwhare. AUP (2025). RRP: $49.99. PB, 304pp. ISBN: 9781776711529. Reviewed by Vaughan Rapatahana.

Mau anō e to mai te ika ki a koe. Ki te tino wawata koe ki te ika ka haere mai ki a koe! You create your own luck. If you wish it, the fish will come to you.

Whakataukī such as this stress just how integral fish and fishing have always been to ngā iwi Māori—all manner of fish and shellfish, be they seawater or freshwater. Mana Moana cogently presents this existential and spiritual significance for all Māori from well before any European arrivals to Aotearoa, a weltanschauung (worldview) that accentuates a harmonious, holistic approach to maintaining and nurturing fish, fishing, and fishers along with tremendous respect for Tangaroa. After all, Te ika tuatahi, mā Tangaroa. Ka whakaaro nui te tangata mō te moana me te taha wairua, ka hoki mai he kai ki a ia. The first fish goes back to Tangaroa. We think the first gift to the sea will bring us luck.

In a steady chapter-by-chapter procession through more recent history, Carla Houkamau and Robert Pouwhare outline the manifest restrictions on and outright revokings of Māori traditional fishing tikanga by Europeans, through to the more recent efforts to balance the scales back towards ēnei iwi, such as the seminal Tiriti o Waitangi Fisheries Settlement in 1992—given that not all iwi agreed about such efforts. The concluding chapters consist of considerable discussion about the leading Māori fishing rōpū, Aotearoa Fisheries/Moana New Zealand, which was finally created in 2004 after years of inter-negotiations, and involves ownership by 58 iwi shareholders. This latter portion of the book also ruminates on the current and potential future exigencies associated with the fishing industry, particularly from a Māori perspective, with a strong accent on kaitiakitanga, or guardianship and protection, of te moana, ngā awa, ngā roto and all life forms in and on them. In other words, the pronounced emphasis in the final pages is on mana o te moana or authority over seas and lakes by and for ngā iwi Māori katoa.

Overall, Mana Moana is a valuable written source about a vital resource for all the people of New Zealand. Ultimately there is a need to balance ecological and environmental factors pertaining to sustainable fishing with both profitable commercial and economic returns, and also with non-commercial access to kaimoana by Māori, whereby for example, it is available for important events such as tangihanga. As such, all parties need to be involved in attaining such balance, given that there remain many issues, as well summarised by Houkamau and Tuwhare: ‘The future of Māori commercial fisheries is marked by opportunities, challenges, and uncertainties.’ Among the latter are climate change, weather fluctuations, soil erosion and sediment runoffs and the concomitant effects on ngā moana, ngā roto, and ngā awa. More, there continue to be political issues whereby changes in government result in different parties presenting different perspectives on what Māori are ‘entitled’ to and divergent public viewpoints about this kaupapa. For example, the innovative Fisheries ITP (Industry Transformation Plan) was retracted by the current coalition government in 2023.

Mana Moana presents this content well through the many photographs, diagrams and graphs positioned throughout this volume. Graphically, these lend themselves to what the authors aim to achieve with this book, as a publication, ‘tailored for educational purposes […] specifically university students new to studying Māori business, culture, and history.’ The text is presented in a clear, systematic fashion, with copious examples and quotations from featured spokespeople filtered throughout. At times, however, the many terminologies and acronyms do become a little confusing, such as ACE, HSS and QMS, although there is a Glossary of Common Terms and Legislation at the tail of the book, which also contains a glossary of ngā kupu Māori. Still, constant reference to the first glossary does eventually edify these various initialisms.

A further key factor to note is the incorporation of several passages in te reo Māori, aligned with translations into te reo Ingarihi. This is necessary, of course, because te reo Māori is another taonga or treasure for ngā iwi Māori, and its nurturing and nourishment parallels that of kaimoana, mātaitai, and kai wai māori (freshwater foods) historically and contemporaneously. An example of this is the multi-page spread of Te Tiriti o Waitangi i te reo Māori, alongside the translation of this into English by Sir Hugh Kāwharu in 1988. Following this on the next page is the English language version of 1840, which does differ markedly from the 1988 version. This emphasises the two quite distinct 1840 renditions and the consequent misrepresentations of what ngā iwi Maōri were led to believe they retained, including full, exclusive and undisturbed sovereignty over fisheries.

Such misalignment led to the evisceration of access to and careful cultivation of kaimoana by and for ngā iwi Māori for decades. It was not until 1992, after prolonged struggle, that they were able to attain and retain what they always had—namely their customary fishing rights as signed for in Te Tiriti o Waitangi, despite the fact that some iwi rejected what was termed the Sealord Deal that year, which further entitled Māori to purchase a 50% stake in that commercial fishing enterprise. The heroes of these struggles are well-depicted with mini-biographies throughout the middle portion of Mana Moana, and consist not solely of Māori.

Kia mate ururoa, kei mate wheke. Fight like a shark, don’t give in like an octopus. Indeed. This whakataukī concisely evokes the decades long wrangling that eventually led to a Māori-led commercial fishing enterprise, Moana New Zealand, which Houkamau and Pouwhare present as being consistently involved in proactive and protective actions regarding te taiao (the environment). They also stress the evolution of fishing technologies, practices, knowledge and the inevitable modifications to the industry, and indeed even to local, individualised, non-commercial and recreational fishing activities, brought about by environmental disruptions and ongoing human re-interpretations and interactions. Accordingly, Ka pū te ruha ka hao te rangatahi. When an old net is worn out it is cast aside and a new net takes its place. Again, such piscine-related sayings reinforce just how central fishing is to Māori, wherever they reside.

Despite these fluctuations, Mana Moana demonstrates that kaitiakitanga always remains the keynote for Māori fishers, of whatever enterprise they are involved in, most especially with regard to Moana New Zealand. A pair of further whakataukī exemplifies this integrated ethos: Toitū te marae a Tāne, Toitū te marae a Tangaroa, Toitū te iwi. If the land is well and the sea is well, the people will thrive.

He tai moana, he tai ika. He tai timu, he ika nunumi. A sea that is healthy, is a sea that flourishes with life. A sea in decline, becomes void of sea life.

For as Steve Tarrant, CEO of Moana Fisheries is quoted as saying, ‘There is a real connection to the moana from our fishers and they are all wanting to protect fisheries […] they’re out there because that’s what they love. That’s their passion. But they also want it there for their mokopuna.’

The future of Māori fisheries is best summarised by another appropriate whakataukī pertaining to our persistent, consistent, intergenerational worldview that fishing is intrinsically related to everything else in the environment, that care for ngā ika me ngā tangata hī ika (fishers) will necessarily entail ongoing ownership and protection of this key industry. Longevity commences with curatorship. After all, He ika kai ake i raro, he rapaki ake i raro. As a fish nibbles from below, so the ascent of a hill begins from the bottom.

Vaughan Rapatahana (Te Ātiawa) commutes between homes in Hong Kong, Philippines, and Aotearoa New Zealand. He is widely published across several genres in both his main languages, te reo Māori and English, and his work has been translated into Bahasa Malaysia, Italian, French, Mandarin, Romanian, Spanish and Esperanto. He is the author and editor/co-editor of over 50 books. His latest is Sexual Predation and TEFL (De Gruyter Brill, 2025).