Black Sugarcane

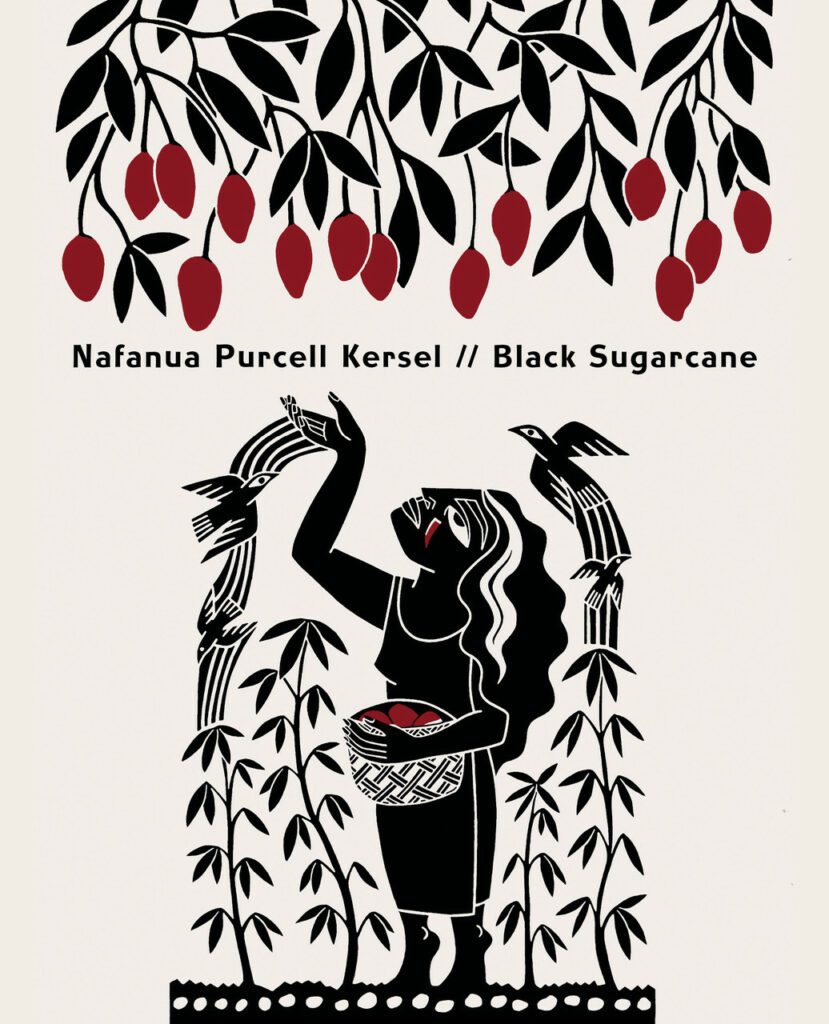

Black Sugarcane by Nafanua Purcell Kersel. THWUP (2025). RRP: $30. PB, 128pp. ISBN: 9781776922222. Reviewed by Māia Te Whetū.

To grow black sugarcane, the plant must be kept in full sun. The canes are dark and sweet and should remain humid to flourish. This debut collection of poetry by Nafanua Purcell Kersel is an embodiment of its namesake, saturated in the same sticky nourishment. Rooted firmly, standing tall among heavy light. Black Sugarcane begins with a poem dedicated to Kersel’s peers and predecessors. Titled “Moana Pōetics,” these words are not only a devotion to fellow poets and writers, but a nod to the story-telling histories of tangata moana.

‘We are a tidal collection, hind waters of the

forever we rally on, to break the staple

metaphors from the fringes.’

The decision to open the collection with this poem gives me the sense that while it is a dedication, it is also an invitation. The author offers the first breath of her book with a welcome, for more “Moana Pōetics” to:

‘sound together on a dance or

bark an intricate rhyme.

We. the filaments of a devoted rope. We,

who contain continuance and

call it poetry.’

Black Sugarcane is sectioned into five parts, named after elongated vowels used in Gagana Sāmoa, ā, ē, ī, ō, and ū. Each part is distinct in its tone and subject matter while consistent in themes of belonging, connection to fanua and its people, and a dissonant but strong sense of home. These poems feel planted in many places at once. As we traverse different oceans, islands and cities, Kersel gracefully positions the reader in the poem’s setting with a grounding fullness that honours the places and people we visit.

Some of my personal favourites, which are featured throughout the collection, are the “Grandma Lessons,” as the author generously shares Grandma’s wisdom on Fashion, Garden, Kitchen, Voice and Work. These poems are delightfully sentimental and warm.

‘If you time your cook for when you want the kids home,

They will follow the smell and wash the dishes […]

If you want to cook well,

Cook enough for your neighbours.

If you want to learn by heart,

be still and watch my hands.’ (“Grandma lessons (kitchen)”)

Kersel shares comedic and frustrating insights into the experience of being a Sāmoan woman in New Zealand and the calculated negligence that is felt interpersonally and structurally. At some points these moments are soothed with the solace and celebration found in small pockets of community—in a church kitchen fighting over clean up with your cousins, in a primary school field sharing a knowing look between siblings, in the slang lexicon emerging from ‘the birthplace of skux.’ (“But Where Are You From? a 90s love song”). In other moments, the author bids that we feel the hurt plainly:

‘It took a minute

to cover someone

with an ‘ie toga

that look lifetimes

of oiled hands

to make soft’ (“Ifoga / Govt apology”)

I was mesmerised and moved by the entire “Fono Ma Aitu” erasure sequence, in which Kersel’s source document was a research paper on Sāmoan mythology and science by Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Taisi Tupuola Tufuga Efl. Her words are powerfully crafted as she pulls a melody from the text:

‘colonial man ate this divinity […] I want to underline the means i was taken by’ (“Artefact V”)

‘like life and death are equal. The beginning of day, the beginning of night invites the earthly divinity to flare […] the malae bonfires they mimic incarnated scraps of sun rise’ (“Artefact VI”)

‘Ī’, the third section of this collection, is dedicated to the devastating 2009 tsunami that struck the Samoan Islands and beyond. These poems are potent with grief and uncertainty, unfolding the intense irreversible loss that still permeates her community. We are merely guests to this pain, and still it is profoundly commanding.

With deft formatting, Kersel invites the reader to inhale this collection in a way that allows the words to move through you and tether to an internal rhythm. She enables us to sit with some words longer than others, to pay attention, to notice the ever-present drumming pulse of the body and its beating. Some poems are grounded in an earthy bass and others are sharp, witty and quick like the Pātē. Most, if not all finish with an encompassing echo of vibration felt long after the words on the page end.

We can assume that Kersel took Grandma’s advice, with prepared and dutiful open palms, when she said, ‘Find a nasal drone in your singing and you will / carry the sound of all the people we come from.’ (“Grandma lessons (voice)”)

Māia Te Whetū (Waikato Tainui, Ngāi Tūhoe) is a takatāpui writer and bookseller born and raised in Ōtautahi. She spends most of her time in the company of the moana, her whānau and growing stacks of books. Her work has been featured in takahē magazine, Awa Wāhine collections and most prolifically, in floating pieces of scrap paper found in jacket pockets.