Shadow Worlds

Shadow Worlds: A History of the Occult and Esoteric in New Zealand by Andrew Paul Wood. MUP (2023). RRP: $55.00. PB, 424pp. ISBN: 9781991016379. Reviewed by Angus Smith.

‘It all distils to a yearning for spiritual experience.’

To the layperson, attempting merely to define the terms ‘occult’ and ‘esoteric’ seems an obscure task, breaching a land cast in shadow. Art and cultural historian Andrew Paul Wood succeeds in telling the story of how these concepts manifested in Aotearoa New Zealand in his latest book, Shadow Worlds: A History of the Occult and Esoteric in New Zealand, beginning with new hybrid spiritualities of the post-industrial era, borne to our shores on colonial lines.

The prominence of India during Queen Victoria’s reign fostered an interest in Eastern religions, while at the same time those disillusioned by modernity cast back to mediaeval and folkloric beliefs from Europe. Wood thus presents to us a broad field that encompasses established organisations such as The Theosophical Society, The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Ordo Templi Orientis, while also examining wider movements including Spiritualism, neopaganism, Satanism, and more. He achieves this in largely chronological order in—the occultly resonant number of—13 chapters, showing how the force of history shaped the adoption of alternative spiritual practices in Aotearoa.

Where are Māori in all this? It is posited that Māori traditional beliefs are more closely aligned with true religion than esotericism, although a grey area undoubtedly lies between. Rātana, a hybrid of Christianity and Māori traditional beliefs with visionary and prophetic aspects, sits closer. The author acknowledges further exploration of this topic falls outside his jurisdiction as a Pākehā historian. Māori are present in parts throughout the book either as members of esoteric groups or as an object of interest for Western occultists who at times incorporated Māori rights and liberation into their ethos, or used exoticised notions of Māori to bolster their own belief systems. I observed too that cults mostly fall beyond the scope of this book, presumably as they are spinoffs of religion with general cosmologies intact.

The book does angle a lens on the scale of occult influence on New Zealand society. Many leaders of social change were committed members of occult organisations, their work likely shaped by teachings and explorations within esotericism. Think women’s suffrage, pacifism, and vegetarianism, to name a few. ‘Occulture’ made space for new ideas that challenged conventional views, and in turn adherents made considerable headway in changing the tone of mainstream New Zealand. Early adopters of Theosophy in the late Victorian era included Prime Minister Harry Atkinson and notable activists Lilian and Kate Edger, sisters who were the first women to attend university in our country.

In the twentieth century, Sir Edmund Hillary was both a Theosophist and core member of the School of Radiant Living from a young age, organisations which stoked his lifelong passion for spiritual and physical advancement. Many of the local esoteric groups discussed in the book may be unfamiliar to readers, yet they often enjoyed wide popularity in their time. For instance, the Havelock Work, an arts and spirituality movement whose endeavours included a syncretic attempt to purify the souls of Havelock North, eventually joined forces with a Golden Dawn expat to establish a new temple there in small town New Zealand to carry on the Golden Dawn rites. The temple Smaragdum Thalasses lasted until 1978, dissolving with a ceremonial bonfire, taking its secrets (including records of politically influential members) with it.

One inevitable quirk of the reading experience is the sensation of being pulled backwards continually, as the author must explain the context of each esoteric movement, (the majority of which came from Britain or the United States), before its arrival on New Zealand shores. Wood notes in his epilogue that ‘for the most part, these groups and movements arrived in a fully developed form.’ Thankfully these backgrounds are usually fascinating in their own right, and he writes with flair and humour throughout, of ‘three British Freemasons with enormous beards’; ‘the melancholy rainbow of Grafton Bridge’; and ‘Von Liebenfels was, to put it mildly, cracked.’

There is a tendency to linger on the usual suspects: Theosophy and the Golden Dawn (and their direct offshoots) together form one third of the book’s length. Wood’s accounting of the construction and architecture of the Theosophist lodges in our cities, plus various changes in address, seems unnecessarily pedantic, until one realises the purpose is to highlight the often overlooked physical and cultural presence of the esoteric in our everyday lives. I recall my dad once rented studio space in a former Freemason lodge on Customs St in the Auckland CBD. As a child I grew accustomed to climbing beneath the Masonic square and compass in the stairwell. The point is, anyone reading this will have similar stories and connections. These days, the Freemasons are mainly associated with their philanthropic work, from bestowing university scholarships to sponsorship of the Auckland Writers Festival Schools Programme.

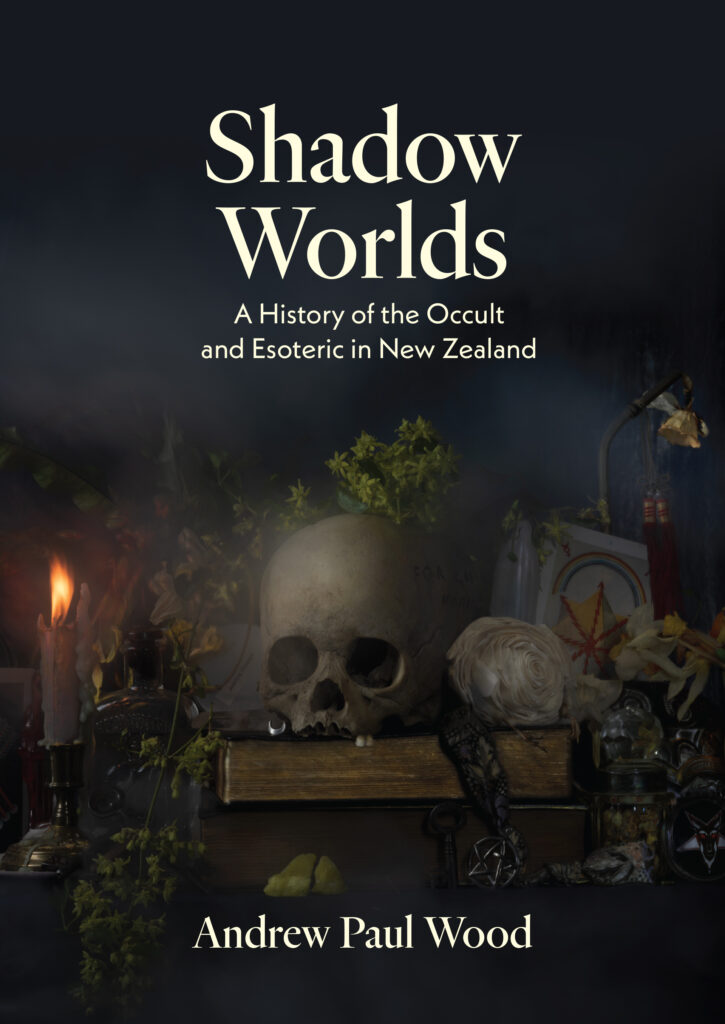

Wood submits that ‘it would take an entire book in itself to look at the influence of occult and esoteric thought on New Zealand artists.’ Yet artistic practice forms such an integral part of occultism’s unique history in Aotearoa, and within the human mind itself, in all its creative permutations and mysteries, there mirrors a level of higher reality in esoteric thought. Perhaps these creators, who took esoteric teachings originating overseas and spun them into something new, were the ones that produced the closest thing to a homegrown occult. In this sense, the Fiona Pardington painting which wraps around the book’s covers presents a promise not fulfilled.

Wood does mention occultism’s influence on the development of literature through renowned author Katherine Mansfield, whose ‘mystical imagination’ was othered and dismissed by many literary nationalists at the time as not belonging truly to a New Zealand canon. That imagination was expanded by her interest and personal involvement in Crowley’s Thelema and Gurdjieff’s The Fourth Way. Her work, of course, proved to be rather influential. Many more artists could have been examined, and provide fodder for a more focused book.

As it is, Wood’s work brings to light an unheralded yet essential strand of Aotearoa New Zealand’s history, without exhausting it for those curious seekers among us.

Angus Smith is an op shop professional and opportunistic writer from Auckland, with roots in Oxford and Aberdeen.