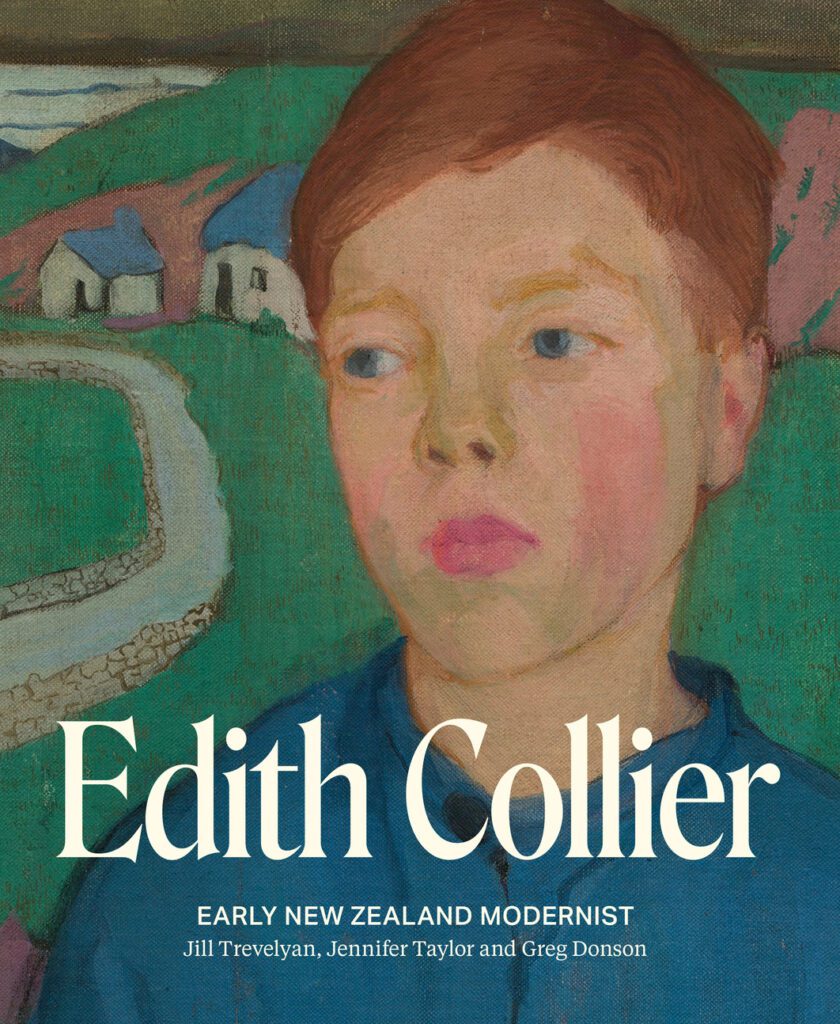

Edith Collier: Early New Zealand Modernist

Edith Collier: Early New Zealand Modernist by Jill Trevelyan, Jennifer Taylor and Greg Donson. MUP (2024). RRP: $70. HB, 256pp. ISBN: 9781991016768. Reviewed by Jenny Partington.

Edith Collier: Early New Zealand Modernist paints a portrait as vivid and lively as one of Edith’s own artworks. Despite working alongside celebrated artists such as Frances Hodgkins, Edith was one of many women who fell between the cracks of art history. Moving seamlessly between fragments of personal storytelling, conversations, and critical essays, this publication captures her life with warmth and vibrancy. This illumination of her life and work is not only an important art historical record, but a sincere collection of memories connecting the many people and communities that remember and value Edith Collier.

When we are first introduced to Edith in chapter one she is 35 years old, painting in St Ives, France, in the summer of 1920. Within the first few paragraphs, it is made clear that she must return home to Whanganui due to her parents’ financial situation. In opening with this pivotal moment, the editors highlight just how important her journey from Europe back to Aotearoa was. We later discover that this was the moment that halted Edith’s blossoming career as a modernist painter.

Edith returned to Whanganui when her parents could no longer support her financially in Europe, and took up the duties of the eldest unmarried daughter. Her family, most notably her elderly grandmother and 37 nieces and nephews, became her greatest priority. She could only paint when time allowed, and towards the 1940s she stopped painting altogether. Domestic responsibilities weren’t the only catalyst for this—many contributing factors are outlined, including financial, societal, and cultural pressures. In her opening chapter, Jill Trevelyan describes the challenging climate faced by artists at the time, especially those committed to modernism, and ‘those challenges were compounded in Edith’s case by her gender, personality and temperament, and also by her family environment.’ Despite the confidence she had developed in Europe, Edith’s work was savagely critiqued by her local community. Some of her finest works were destroyed when her father, outraged by a collection of nude portraits in her studio, decided to burn them. On top of this, though her works were exhibited occasionally throughout Aotearoa, Edith rejected the idea of self-promotion, meaning much of her work went unseen by the public.

With Edith situated beside her successful mentors Frances Hodgkins and Margaret Preston throughout, the privilege needed to sustain a successful art career during the early 20th century is made clear. The question is posed early in this book: How would things have been different for Edith if she had been able to stay in Europe? Would the name Collier be as commonly known as Hodgkins or Preston?

By observing the factors that impacted Edith’s short-lived career, but not dwelling on them, the excellence of her work is forefronted. The many ‘what ifs’ of Edith’s life could probably fill their own book, but while they are treated with care and consideration throughout Edith Collier: Early New Zealand Modernist, they certainly don’t take centre stage. No excess mourning for what could have been looms through these pages, and therefore no shadows are cast across Edith’s great achievements.

Despite Edith’s near abandonment of her practice on returning to Aotearoa, this book highlights the impact that her work had on the communities around her. Chapters venture into finer details of her artistic career, sectioned by her time spent in Ireland, St Ives, London and Kāwhia. Short stories, poems and essays are woven between images of the works made during these periods, creating a picturesque journey following Edith’s artistic progression.

Stories from the descendants of those she painted, and from her own family members, hold special weight. Jim Cullinan from Bonmahon, a small Irish village, had grown up hearing stories about Edith and her visits to the village, particularly the time she had painted his mother. He said, speaking of his mother: ‘She often said then, over the years, I wonder what happened to Edith Collier. I wonder was she ever a famous artist.’ An essay from Esther Tooman describes the fascinating life of her great-grandmother, Tiro Tiro, who was painted by Edith in 1928 in Kāwhia. Gordon Collier, Edith’s nephew, warmly describes his Aunty Edie, recounting her elaborate breakfasts served with fresh fruit, warm dates, and scrambled eggs. Essays analysing artworks and their technical prowess, when paired with small yet detailed anecdotes such as these, create a rich and varied reading experience that vividly captures both Edith and those who she painted.

Like many women artists of the early 20th century, Edith Collier’s career was stifled at an early age. However, the focus of this book isn’t on Edith as a ‘forgotten’ woman artist—for it is clear on reading that many people actively remember her. We are introduced to Edith through a kaleidoscope of memories, seeing fragments of her life as an artist, student, feminist, spinster, sister, and aunt. This book remembers Edith Collier in three dimensions, layered and complex, alongside her equally layered collection of artworks that remain as exciting and contemporary as if they were painted today.

Jenny Partington is a designer, writer, and photographer living in Ōtautahi Christchurch. She currently works as a Graphic Designer and Marketing Coordinator at Ashburton Art Gallery and Museum and enjoys writing in her spare time. She completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts with Honours at the Elam School of Fine Arts in 2020, and a Postgraduate Diploma in Art Curatorship at the University of Canterbury in 2022.