Bird Life

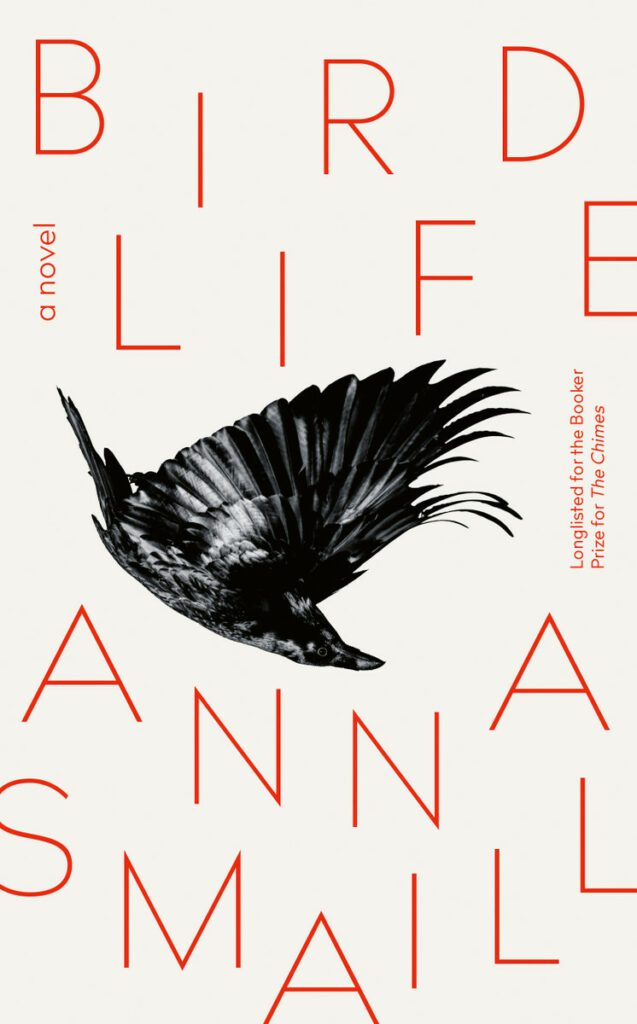

Bird Life by Anna Smaill. THWUP (2023). RRP: $38.00. PB, 296pp. ISBN: 9781776921249. Reviewed by S. J. Hook.

No one wants to begin a literary review quoting 90s self-help guru Steven Covey, author of 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Especially since our two main protagonists, Dinah and Yasuko, may not be who Covey had in mind when visioning a world of highly effective people. His quote however, ‘We see the world, not as it is, but as we are’ resonates with Anna Smaill’s new novel, Bird Life.

Set in contemporary Tokyo, Dinah, a 20-something New Zealander, arrives, reeling from the recent loss of her twin brother, to teach English to engineering (read male) university students. Her counterpart is an older woman, Yasuko, in her 40s who works at the same university in an adjacent department also teaching English and who, beyond her immaculate presentation to the world in both makeup and dress (an elaborate armouring of ‘camouflage and candour’ p.12), has had a lifetime of intermittent communication with life that surrounds her in all its many and varied forms:

‘Yasuko came into her powers when she was thirteen. . . . When the cat spoke to her, the voice it used was her own voice as if this might moderate her shock. The air was suddenly electric. The buzz of everything, the particles alight.’ She experiences the magic of connection and communication as both a joy and a burden: ‘The world was very beautiful. It was given to her fully at this time. She saw it all. . . . There were patterns everywhere; all filled with meaning.’ (p.30)

Steven Covey’s quote can be equally applied to the experience of the reader encountering Smaill’s book. Through my own experiences of both unravelling and bearing witness to the sometimes greater unravelling in others, I was unable to consider Yasuko’s or Dinah’s experience of the world as ‘madness’ or magic-realist. Instead, the author offers a doorway into experiencing the world in a different way: senses are heightened; time stretches and pings; meaning can be found in unusual places and spaces.

More than once, I had a vision of Smaill as a giant conductor keeping an unrelenting yet steady beat, holding back the mounting tension through her control of the tempo—slow and taut—a little like the music of early 90s band ‘Talk, Talk’ as the point of view switches between Dinah and Yasuko: breathe in, breathe out.

The pace, coupled with the sensual prose, brought me such pleasure that my reading experience slowed to something more spacious—to give dignity and respect to the lyricism that her writing deserved. My favourite paragraph takes place in the not-quite park opposite Dinah’s apartment where she spends her nights somewhere between sleep and wakefulness, a subliminal space where memories of her brother, Michael, loom large:

‘Her twin brother used to twist the grapefruit right off the tree and bite through the skin and the horrible white pith so that the juice ran down his chin. That was the kind of person he was. They were her brother’s fruit; she didn’t even really like them. Something morose and sharp and rebarbative about the taste and the way their heavy oil hung around. She smelt it now, the sourness and the sweetness. It asked you to go back to your body in some way, like plunging into very cold water.’ (p.11)

Far away from the world of personal improvement and Stephen Covey’s human potential movement, Dinah and Yasuko offer us a mirror to question what is reality and to ask whether our conventional and accepted experience of the way things are—typically an immersive experience of being elsewhere, distracted and lost—is not perhaps a type of madness in itself?

Sarah J Hook grew up in the library, literally, it was her surrogate parent after her parents divorced. The library, complete with nooks and crannies, became her sanctuary and fed her a daily diet of prose and pictures. Reading is her solace, her lifeblood, her past, her present and her future.