A garden is a long time

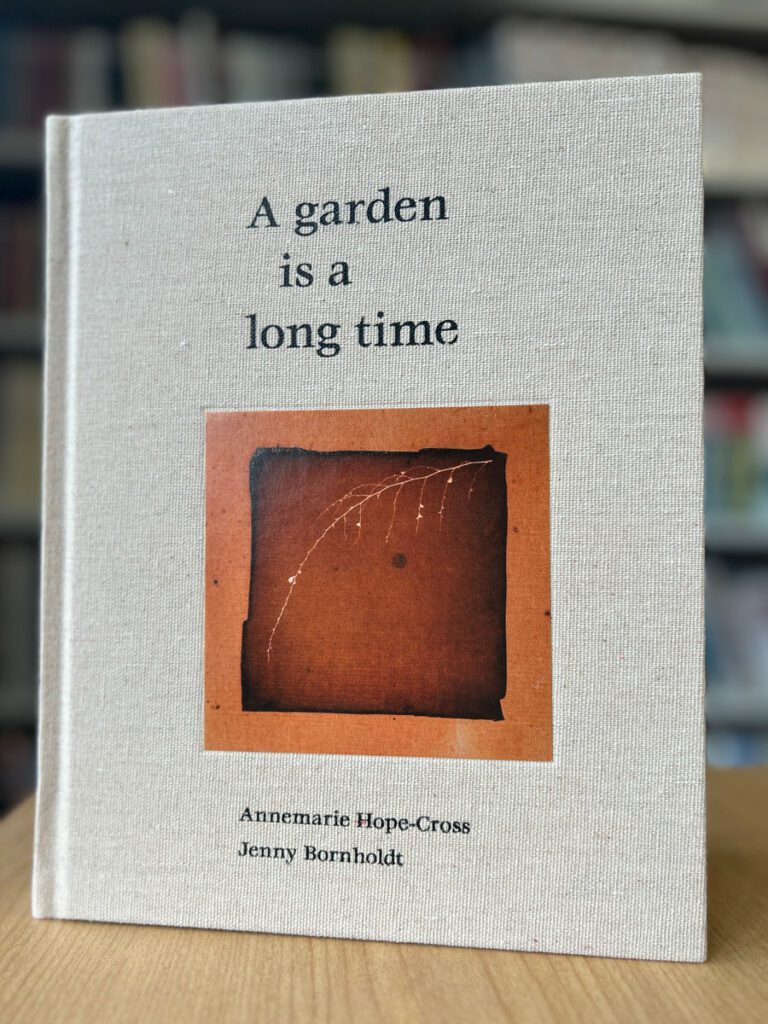

A garden is a long time by Annemarie Hope-Cross and Jenny Bornholdt. THWUP (2023). Published in association with Rim Books. RRP: $50.00. HB 151pp. ISBN: 9781776920839. Reviewed by Michelle Elvy.

I find myself going back to this book time and again. In fact, it invites us to go beyond notions of time—to sit with objects, images and ideas for a moment or longer, to reflect, and to see what might become. Every page is an invitation to consider light and dark. We see black/white/grey with the opening lines, written by Bornholdt, that take us into the story of the artist, Hope-Cross:

‘What she wanted to do most was to ride her triathlon bike fast in a straight line.

In much the same way that light travels through space, or through a camera lens, or falls on light-sensitive paper which a plant or plants might be placed upon.

And to make photographs.’ (p.9)

At one level, the book is about an unfolding of process. The artist wanted to explore—but the ‘how’ of it was unclear. Her curiosity took her on a path to the past, and her work used analogue photographic processes from the 1830s and 40s, knowledge gathered from her father and grandfather, and from her engagement with other important photographic developments. She found her own way of reproducing elements from nature with cyanotype and anthotype processes. Her work connected across time. Later, when she started making larger works, there hung a photograph of Castlepoint lighthouse, Wairarapa, taken by her grandfather—‘Grandfather signalling granddaughter down through the years,’ as Bornholdt notes (p. 89).

We witness milestones as we move through early childhood and teen years, then art school and England. Her interest in William Henry Fox Talbot, who first invented the photogenic drawing process, impacted everything that followed. It was when pursuing Talbot all the way to Lacock Abbey, where he had lived with his wife Constance, that Hope-Cross found her spark: ‘I realised this was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life’ (p. 27). It was in England, and with these discoveries, that time began to matter. For Hope-Cross, processes of photography meant ‘a sense of slowing down’ (p. 27). There is nothing rushed about her images; one sees blurry edges and a suggestion of what might be discovered behind, underneath or within. She developed ‘a fascination with light and shadow and what they can do, what can be done with them’ (p. 12). All of this takes time to see—to really see.

From Auckland to Central Otago, and then further afield to England, then back to New Zealand, Hope-Cross’s life unfolds through images, through Bornholdt’s poetic language and through Hope-Cross’s diary and letters. She connected deeply with all the places where she dwelled: her childhood cottage in Central Otago; Alexandra and the rushing waters of the Manuherekia and the Clutha; Lacock, Wiltshire; Invercargill, where she worked at the Blind Foundation; Christchurch, where she went for radiation treatment. Place weaves with her art; her view is set down in her work.

One wonderful moment is about Hope-Cross meeting her husband. This is the beginning of their love story:

‘Both had grown up in darkrooms and loved photography. Eric Schusser taught Annemarie to ski cross-country. Later he offered her a diamond engagement ring, but she asked for a darkroom—light exchanged for dark, which then makes light—so Eric built her one.’ (p. 37)

Her life with Schusser happened in a stone house, with a garden. Everywhere in that garden she saw movement, change: life. Here is a small poem that appears in this part of the book, Bornholdt’s “Larch”:

‘Garden constant

but changing.

There’s weather.

Sky crisp as a good apple.

A hoar frost fixes white

for days.’ (p. 40)

Bornholdt captures the sense of light and space, of time. Of change. The suggestion of weather might be about the garden, or something more.

With excerpts from Hope-Cross’s diaries and letters, we see the world through her gathering process, including colouring in. In the middle of the book is the story of her cancer, and here we see how her ‘Still’ series came to be. ‘I realised I could make images of the bottles, what they were used for, their links to things, their meanings’ (p.65). As Bornholdt writes: ‘The idea of using a mousetrap camera to make “slow” images of the vessels seemed a salve to the chemotherapy, major surgery and radiation she knew were ahead of her’ (p.66). And the slow process was intertwined with that part of her life: ‘using the mousetrap camera. . . , with exposure times of up to eight hours, gave me time to rest’ (p.66). In this series, she produced shadowy images of bottles that belonged to her grandfather (bottles for photographic chemicals), her mother (perfume bottles) and family bottles (chemistry bottles, connected to their long family association with photography) (p.72). Again, here is process that compresses time—or stretches it, I’m not sure which—onto the image, onto the page.

Annemarie Hope-Cross died in late 2022, as this book was going to press. How fitting that this book feels so timeless. In these pages process is greater than the individual; it’s a study of photography as process, of life as process. Wonder is in the pages. When describing her process of shadow work, Hope-Cross noted: ‘This is merely about the joy of shadows and sunlight and how you want that to be’ (p.116). Bornholdt captures an urgent and fleeting reality in the poem “Mortal” (p.87)—and yet, also, the garden is in these pages, beginning to end, boundless:

‘that colour! Seed heads

for the birds for the shapes and for

moonlight leaves leaves light

coming through ideas

coming through the leaves. (“Garden at Larch Crescent with Annemarie,” p. 105)

Boundless. Hope-Cross’s life and work is held in this book but not captured; it’s on the page but free; it’s there in the curly smoke at the edges. And it’s here, too, so beautifully penned by Bornholdt:

‘Gratitude to the garden

for its doggedness, its miracle—when we can only

look and hope—and for

the sudden violet

nub of green

these things we love

each dangerous day.’ (“Thanks be,” p. 114)

Michelle Elvy is an editor, manuscript assessor, writer and creative writing teacher. Her books include the everrumble and the other side of better, and her anthology work includes, most recently, A Kind of Shelter: Whakaruru-taha (MUP 2023). She edits at Flash Frontier and AT THE BAY | TE KOKORU.